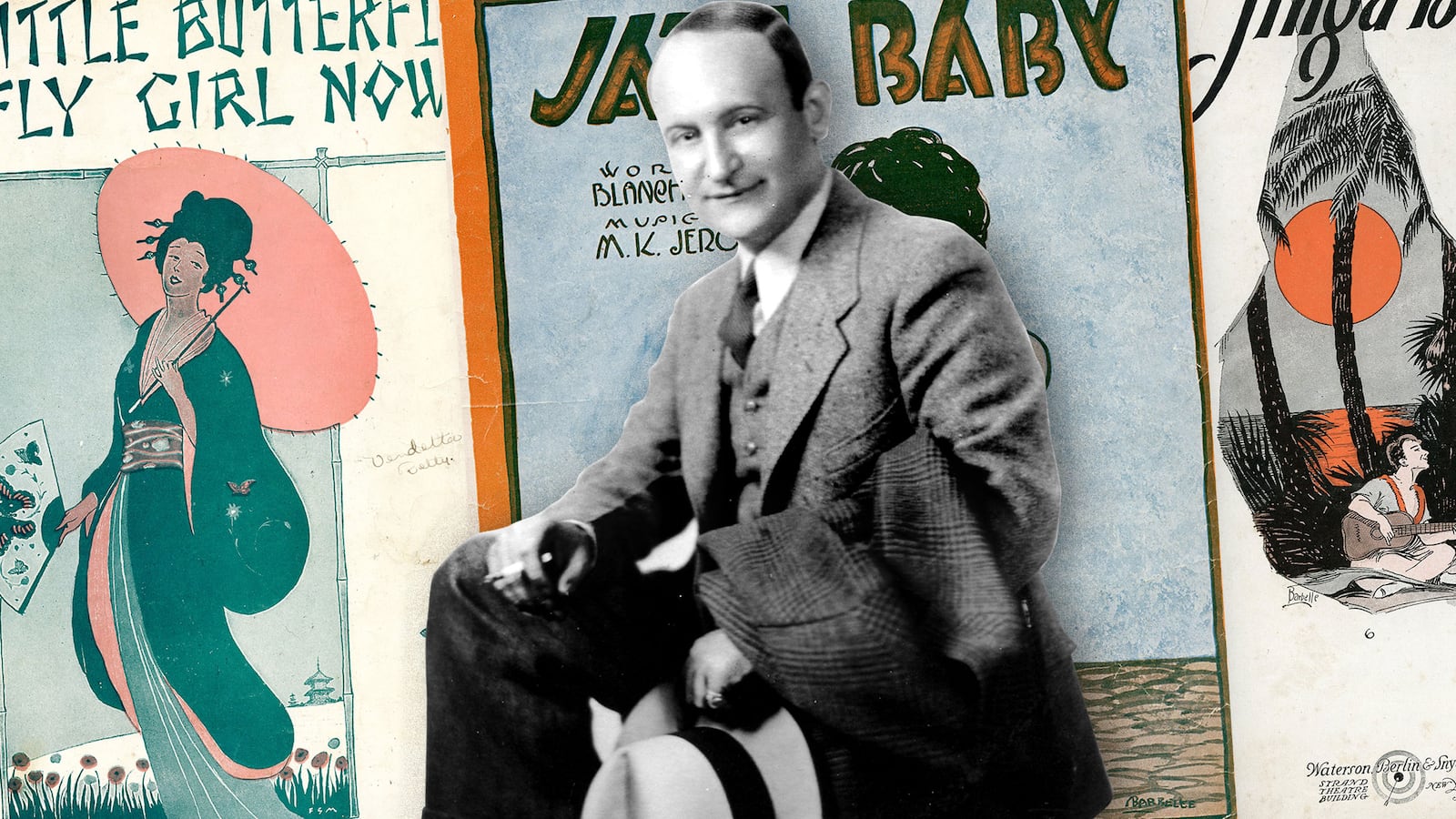

During the half century from 1911 to 1967 that my grandfather, M.K. ("Moe") Jerome, was a songwriter on Tin Pan Alley and then at the Warner Bros. movie studio, reporters always asked him where he got the "inspiration" for his songs. Moe strongly rejected that notion. It wasn't "inspiration," he insisted: It was all about "compensation." Songwriting was a job, nothing more.

When he wrote songs for the publishing firm of Watterson, Berlin & Snyder, from 1911 to 1929, he created music to fit the popular mood—songs that would sell. In the ’20s, it was jazz and flappers, so this young "tunesmith" (as they were known) wrote "Jazz Baby," "Sally Green (the Village Vamp)," and "Poor Butterfly Is a Fly Girl Now."

When "Dixie" songs were in vogue, he wrote "Sewanee Sue" and "My Mammy Knows."

When the nation yearned for novelty songs, he gave them "Jinga Bula Jing Jing" and "Everybody Yell Meow—Let's See If Kitty's Home."

At Warner Bros. from 1929 to 1949, he wrote, not for the masses, but for a film's producer who wanted a song for a comedy or a western, or a drama or a musical. Take, for example the 1945 film San Antonio, starring Errol Flynn and Alexis Smith. Moe's instructions from the producer were terse: "Write a song for Smith to sing in a dance hall number." Nothing could have been easier for Moe, who had written such numbers for many westerns during his years at Warners. He and his lyricist partner, Ted Koehler, quickly created a lovely ballad called "Some Sunday Morning." End of assignment. No inspiration was required.

The film was an instant hit. So was "Some Sunday Morning." It was Flynn and Smith's romantic theme song. Every time the two appeared on screen, the melody played in the background, courtesy of the film's composer, Max Steiner. Smith sang it in a large production number set in the local saloon, although her voice was dubbed by staff singer Bobbie Canvin.

As early as January 5, 1946, the song made Billboard's "Honor Roll of Hits," a list denoting America's top tunes. It charted at Number 9. Sales of sheet music were also excellent: for 14 weeks, the song was in the top five. And early in 1946, the song was nominated for an Oscar for Best Song.

On one occasion, however, inspiration played the major role in the creation of what would be M.K. Jerome's first and perhaps greatest hit, the one that launched his career and that would eventually take him to Hollywood.

It came during World War I when he was 24 years old and working as song plugger for Irving Berlin's publishing firm. Prior to the declaration of war, Americans had hoped to avoid involvement in Europe's toxic affairs. Tin Pan Alley played to the public's isolationist mood with such songs as Albert Von Tilzer and Will Dillon's "Don't Take My Boy Away."

After Congress declared war in April 1917 and the Wilson administration whipped up an anti-German hysteria that swept the country, "the dominant tone was belligerence," notes journalist David Hinckley. "America, Here's My Boy" was sung by such popular artists as Elsie Janis and the Peerless Quartet, while John Philip Sousa set it to a march.

"America, I raised a boy for you," went Arthur B. Sterling's lyric.

"America, you'll find him staunch and true,

Place a gun on his shoulder,

He is ready to die or do.

America, he is my only one;

My hope, my pride and joy,

But if I had another,

He would march beside his brother;

America, here's my boy."

Other similar hits were "Hunting the Hun," recorded by Arthur Fields in 1918, and especially George M. Cohan's celebrated "Over There," sung by the most popular artists of the day. The Wilson administration rewarded the patriotism of American song writers by exempting their publishers from its policy of paper rationing. Sheet music was as important as arms production.

Moe was immune from the patriotic fever. His wife's older brother Jacob was drafted and fought in France but found trench warfare so harrowing that he was discharged from the army within the year. His wounds were psychological. Today he would be classified as suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; then, he was considered "shell shocked." He never uttered a word again and spent the rest of his life living in the attic of his parents' home on Long Island, isolated from the rest of the family.

Eventually, more than 117,000 Americans would die fighting “over there.” So it's not surprising that Moe's songs focused on the home front, on the mothers and daughters who waited desperately for some word of the sons or father in harm's way.

Moe had high hopes for a particular melody he wrote, a kind of lullaby he often hummed when he put his young son to sleep. But he wanted this song to be a statement about the cost of the war, what it did to those left behind.

He brought the melody to two of Tin Pan Alley's greatest lyricists, Sam M. Lewis and Joe Young. They loved the tune and shared Moe's sentiments. Thus was born "Just a Baby's Prayer At Twilight (For Her Daddy Over There)." Its success depended upon which artist introduced the song and who might be persuaded to record it.

Moe thought immediately of Belle Baker, with whom he had worked when she visited the offices of Waterson, Berlin & Snyder looking for new material. Baker, a 24-year-old veteran of the Yiddish theater, had a rich and passionate alto voice. She was one of vaudeville's biggest stars despite her unattractive physique; one critic likened her to a "tank bowling over everything in the way." Still, "she knew how to put a song across," notes Laurence Bergreen, Irving Berlin's biographer, "laughing and crying almost simultaneously and compelling an audience to listen."

Baker was a major headliner while Moe was just a young song writer whose 11 songs were only modestly successful. He thought his chances of winning her support were poor.

But when she stopped at the office one day that September, Moe approached her and she agreed to listen to "Baby's Prayer." Her face lit up, Moe later recalled. She loved it, she said, it was her kind of song, richly emotional, one that told a story that packed a punch. She was about to start a 10-week tour of vaudeville houses in New York state, and she agreed to introduce it at one of them. And as personal favor to him for his help in many earlier rehearsals, she would not a charge the weekly fee (often as high as $100) that vaudeville's biggest stars often demanded to perform songs in their act.

"Just A Baby's Prayer At Twilight (For Her Daddy Over There)" debuted on Tuesday, November 21, 1917, at Keith's Bushwick Theatre, Brooklyn's largest and most magnificent vaudeville theater. Ethel Barrymore had played there, as had Lily Langtry, and it was equipped to accommodate the dogs, monkeys, horses, and elephants that made up popular animal acts. None appeared at that day's matinee, however: the bill consisted of Marguerite Farrell, known for her hit "Naughty! Naughty! Naughty!"; Cowan and Bailey, a piano-banjo act; Ed Martin, a singer; and the headliner, Belle Baker, who came on next to closing.

The theater, which seated 2,500 patrons, was "all filled in from bottom to top," noted Variety's founder Simon J. Silverman, nicknamed Sime, who was covering the event. Baker sang eight songs, but it was the sixth, "A Baby's Prayer At Twilight For Its Daddy Over There [sic]," that "was the big noise."

"I've heard the prayers of mothers," Baker began, speaking passionately rather than singing the song's introduction,

“Some of them old and gray.

I've heard the prayers of others

For those who went away.

Oft times a prayer will teach one

The meaning of good bye.

I felt the pain of each one,

But this one made me cry."

Then she let loose in a loud melodic voice:

"Just a baby's prayer at twilight

When lights are low

Poor baby's years are filled with tears

There's a mother there at twilight

Who's proud to know

Her precious little tot

Is Dad's forget-me-not

After saying ‘Goodnight, Mama’

She climbs upstairs

Quite unawares

And says her prayers

'Oh! kindly tell my daddy

That he must take care.'

That's a baby's prayer at twilight

For her daddy, "over there.'"

Then Baker spoke again, softly this time:

"The gold that some folks pray for,

Brings nothing but regrets

Some day this gold won't pay for

Their many lifelong debts.

Some prayers may be neglected

Beyond the Golden Gates.

But when they're all collected,

Here's one that never waits;"

Again, she sang in a voice that reached the farthest rafter:

"Just a baby's prayer at twilight

When lights are low

Poor baby's years

are filled with tears.

There's a mother there at twilight

Who's proud to know

Her precious little tot

Is Dad's forget-me-not

After saying, ‘Goodnight, Mama,’

She climbs up stairs

Quite unawares

And says her prayers

'Oh! kindly tell my daddy

That he must take care.'

That's a baby's prayer at twilight

For her daddy, 'over there.'"

She had the audience in tears with this tale of a young girl's prayer, a fervent hope that her soldier father would "take care" and return to her from "over there." Variety’s Silverman thought the lyric "brilliant" and the melody "beautiful." "It sounds like the best war ballad of the year,” he wrote, “one of those quick hits." After she sang it, he noted, Belle Baker "became an applause riot.”

Baker sang it again during her next appearance at Keith's Colonial Theatre on Manhattan's upper west side on the evening of December 3. That night she sang nine songs to an audience that numbered almost 1,400 people, and again it was "Just a Baby's Prayer At Twilight" that stood out. One critic called it "the most melodious song Miss Baker has sung in a long time ... and what a number that is! Between the melody and the way she puts it over. Oh boy!"

Waterson, Berlin, & Snyder, sensing that they might have a hit on their hands, had already began mounting a major publicity campaign. Their chief artist and designer, Albert Barbelle, was assigned to create the cover. Eventually, he crafted a beautiful illustration depicting a young blonde girl, perhaps about five (a doll rests against her white pillow), wearing a white nightgown, eyes closed, hands clasped together prayerfully, kneeling on her bed. The background is a reddish brown, so the child, clad all in white and kneeling on white sheets, stands out vividly. The firm's army of song pluggers took to the streets throughout the city and beyond, and sheet music appeared in stores by mid-November. They couldn't keep it on the shelves. One week in 1918, it sold 100,000 copies.

Waterson, Berlin & Snyder bought two full page ads in Variety. The first, which contained Sime's review declared, in bold caps,

"10 DAYS OLD AND ALREADY AN ESTABLISHED HIT—

JUST A BABY'S PRAYER AT TWILIGHT

(FOR HER DADDY OVER THERE)

Music by MOE JEROME Lyrics by LEWIS and YOUNG

Introduced at

The Bushwick by

BELLE BAKER

The second printing, published in late November, printed the verse and the chorus and made even greater claims for the song, calling it

THE MASTER BALLAD OF THE AGE

A Thrill In Every Line

There was more. "Baby's Prayer" was "The greatest constructed song ever published. You hold an audience spellbound until the very last word." The firm urged singers to "Wire, write, phone or call for orchestrations. Don't wait."

Singers and orchestra leaders did respond. Henry Burr, the noted tenor with many hits to his credit, was the first to record "Just a Baby's Prayer at Twilight" on December 6. Others followed: Charles Hart, another successful tenor; Prince's Orchestra led by Charles A. Prince who had been making music since 1891, turned the melody into a fox trot. The Edna White Trumpet Quartette, the first all female group of its kind, recorded a jazz version of the melody, And Pietro Deiro, an Italian immigrant who found success with the accordion, transformed the melody into an accordion fox trot.

Prince's Orchestra's version landed at six on the Billboard Top Ten chart in January, Charles Hart's at 10 in June, but it was Henry Burr's version which catapulted the song to number one in April 1918.

Burr was a 35-year-old Canadian whom some would later call "the first King of Pop." No singer was more prolific. He was said to have recorded more than 12,000 records during his career, using nine pseudonyms. His biographer, Arthur Makosinski, described the crooner's voice as "silvery ... [with] rare sympathy and charm ideally suited to the recording medium." "Just a Baby's Prayer at Twilight" was Burr's first million seller at its full price of 75 cents. The number grew to two million and it remained at number one on Billboard's chart of best sellers for 15 weeks, longer than any other song on the list in 1918. It also sold three million copies of sheet music including a French edition.

Eventually, it became the second best selling song in the second decade of the 20th century. (The first was "Casey Jones" by Billy Murray.) At 24, M.K. Jerome had the number one song in America in 1918.

The song, now almost one hundred years old, has endured. Singers like Bing Crosby, Buddy Clark, and Britain's Vera Lynn recorded it during the Second World War. So did Benny Carter, the great jazz trombonist, with Savannah Churchill providing vocal accompaniment. In 1946, country-western star Wesley Tuttle and his Texas All Stars sang it, and it was included in a posthumous album published in 2017. It can also be found in Michael Feinstein's album Over There, published in 1990.

Two recent versions, sung acapella by New England Voices in Harmony and Double Feature, a male chorus, are especially beautiful and are available on iTunes. That so many different renditions exist—ballad, swing, jazz, country-western—reflects Moe Jerome's ability to write music that transcends the time in which it was written.

"Baby's Prayer" led to other hits in the ’20s and, in 1929, took Moe to Hollywood with the first group of Tin Pan Alley men chosen by Warner Bros. to write music for talking movies. He worked on James Cagney's early films and played an important role in Cagney's favorite, Yankee Doodle Dandy. He tried, and failed, to turn Bette Davis into a singer in Kid Galahad. With his lyricist Jack Scholl, he wrote the only original song featured in Casablanca. He wrote songs for the films of John Garfield, Ann Sheridan, Errol Flynn, Olivia De Havilland, Edward G. Robinson, Dennis Morgan, Jane Wyman, and Dick Foran, "the Singing Cowboy." "Sweet Dreams, Sweetheart," written with Ted Koehler for Hollywood Canteen, won him his first Academy Award nomination for "Best Song" in 1944. He was nominated again the following year for "Some Sunday Morning," written for Errol Flynn's western San Antonio.

Why tell his story now (as I'm currently doing in a book) 40 years after his death in 1977? Why tell it at all? Because while we know the lives of the great stars, screenwriters, producers, and directors of the so-called "Golden Age" of American film, we know little about the men and women whose names appeared not just below the title but in the credits, when they appeared at all. One journalist writing in 1941 called my grandfather "the short order cook of the Warner Music Department, whipping together ditties to order like Henry Kaiser does ships, but also because for some 16 years M.K. has been a stalwart pillar of song."

What was it like laboring in the boiler room of the great studios, stoking the engines which allowed the production of hundreds of films every year, many forgettable but some authentically great, from the ’30s through World War II and the Cold War? My grandfather's generation of song writers are gone now, their names unknown, even to film buffs. With this account of one man's experience, I hope to shed light on this important but overlooked chapter in Hollywood's history.

My grandfather's music survives, despite the end of the studio system and the dramatic changes in national culture and musical trends. Conveniently, his films can be found on Turner Classic Movies (TCM), where typically more than a half dozen of his movies run every month (14 in March 2017), especially the classics, Casablanca and Yankee Doodle Dandy, but other films like Ida Lupino's The Hard Way, Ann Sheridan's Nora Prentiss, John Garfield's Nobody Lives Forever, and Barbara Stanwyck's Christmas in Connecticut, films which have grown in stature and popularity since their original release. His songs can also be heard in more than 70 of the studio's short subjects (called "briefies”) and a hundred cartoons, including, in 1936-37, the opening theme of 32 Merrie Melodies.

His music has also attracted the attention of contemporary filmmakers. The Coen Brothers' O Brother, Where Art Thou (2000) uses a tune he wrote in 1933 for Myrt and Marge, sung by the Three Stooges, while director Callie Khouri chose a Dennis Morgan song, "You, You Darlin'” from 1940's Tear Gas Squad for Secrets of the Ya Ya Sisterhood (2002). Richard Linklater chose "Jazz Baby," written in 1919 and revived by Carol Channing in Thoroughly Modern Millie in 1967, for his 2009 film Orson Welles and Me.

Television's global reach has brought his film music to 22 countries throughout the world, to eastern and western Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia. Contemporary artists are covering his work as well. San Francisco's Janet Roitz has sung his songs on her blog "Fabulous Film Songs." And Toronto's Alex Pangman recently featured "Through the Courtesy of Love," written originally in 1936 for Here Comes Carter, on two of her albums.

And it all began with a tribute to his brother-in-law maimed in World War I a century ago.