In the years after the war, Britain was awash with stories and images of Nazi hell. The war crimes trials had revealed the full horror of what Hitler had done. Books like Lord Russell of Liverpool’s “Scourge of the Swastika” made the front pages and topped best-seller lists for months. When he was five, Martin Amis saw one of these lurid accounts accompanied by pictures of the railway tracks and crematoria of Auschwitz. Unable to understand them he asked his mother to explain. “Oh don’t worry about the why’s and where fore’s of Hitler,” she said. “You’ve got blond hair. Hitler would have loved you.”

Sixty years on, his hair no longer so blond or so abundant, he is still seeking an explanation for what his friend Saul Bellow called “the terminal point so far in human evil.” His astonishing new novel “The Zone of Interest,” which will be released Sept. 30, is his latest attempt.

It has taken him years. His first published descent into the hell of Auschwitz was in his highly experimental 1991 novel “Time’s Arrow”which narrates the story in reverse order of a camp doctor, one of Mengele’s’ acolytes, from evil back to innocence. At the end of “Time’s Arrow” he very generously credited me (alongside others) for having helped him. Apart from stories I may have told him about members of my Austrian Jewish family being murdered at Auschwitz and elsewhere I cannot recall casting any original light on the “why” of Nazi genocide, nor am I capable of doing so.

This time, with autodidactic zeal, he has dug far deeper. Indeed, in his explanatory afterword to “The Zone of Interest” — a short essay entitled “That Which Happened” — he quotes a line by the Holocaust poet Paul Celan, who thus described the indescribable and demonstrates his prodigious research. His shelves at home in Cobble Hill are said to groan with mighty tomes by the likes of Yehuda Bauer, Raoul Hilberg, Lucy Davidowicz and Victor Klemperer — necessary sources all — as well as dozens more. In his search for an answer to the question “why” he has not merely interrogated the magnae opi, but less obvious ones from the minor arcana, like Anton Gill’s incredibly moving “Journey Back From Hell,” a group portrait of some survivors.

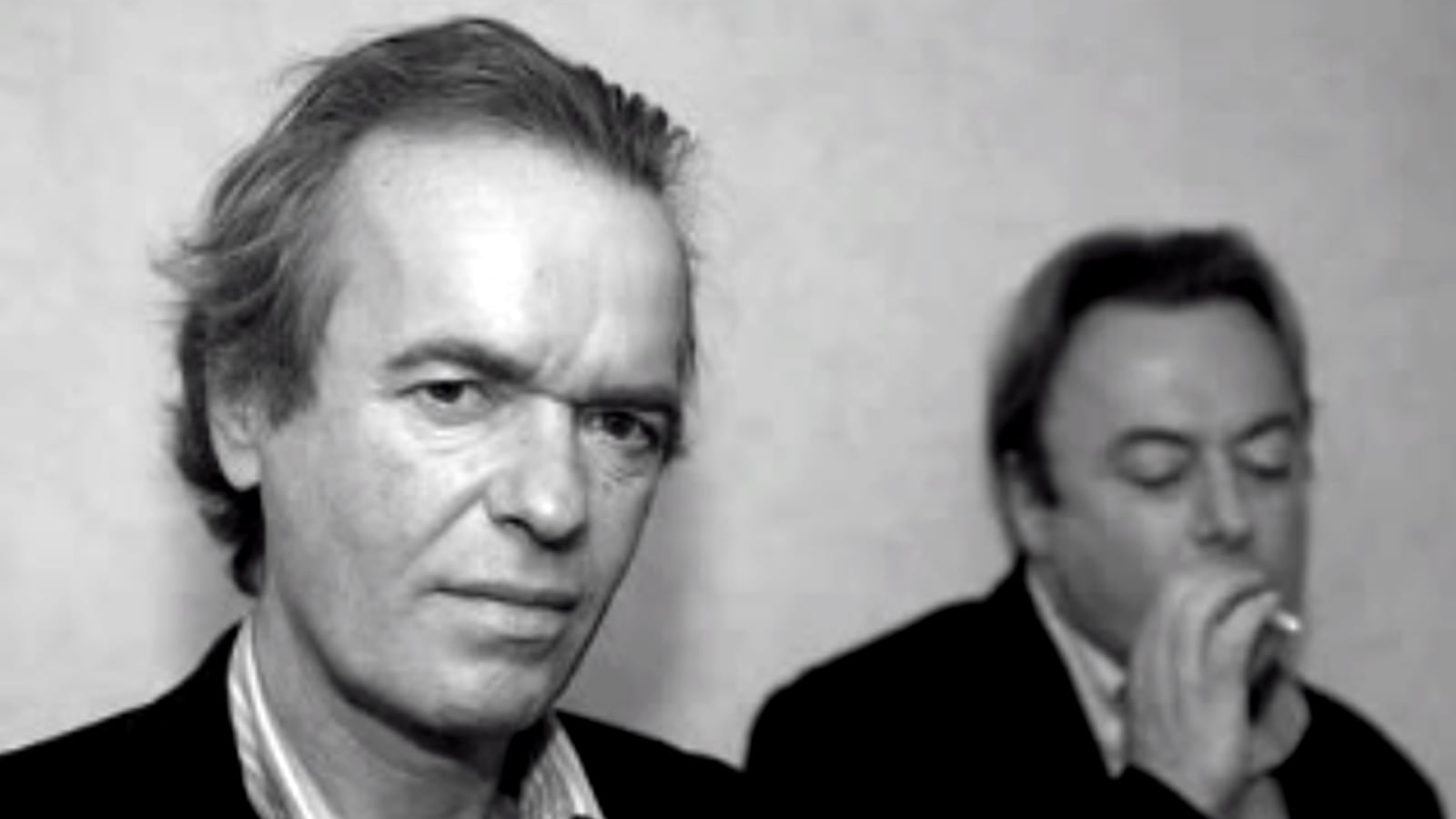

I first met Martin in the late seventies. Gully Wells, my wife, had been his girlfriend at Oxford and when we moved to New York in 1980, he often came to stay, partly for the pleasure of hanging out with his cherished chum Christopher Hitchens who happened to be our lodger. Those were the years of “The Invasion of the Space Invaders,” the book about video games the mature Martin has tried to forget, and the note-taking that fuelled “Money,” the book for which he is best remembered. His time with us on Bank Street — the place where John Self the English comic anti-hero of “Money” stays when he descends on New York — was spent in squalid Times Square arcades mastering Pac Man or around “ruined” tables drinking gallons of vino “tonto” (an Amis-ism), chasing “chicks” (another usage of his in that era) and smoking up a storm (hand-rolled Virginia Gold). Then there was was the word play. Between “Smike” and “Little Keith” (Christopher’s nicknames for himself and Martin), they created an entire dictionary of mainly smutty and mostly childish private phrases to enliven proceedings. “Sock” was a man’s apartment. “Rethink parlor” was the loo and “Having a rethink” was an obvious scatological derivative. And then predictably, there was a long unprintable list of synonyms and phrases for various sex acts. Perhaps you had to be there.

One thing that was definitely not there in our apartment in the early ’80s was any talk of the Holocaust or of the two other great moral challenges to civilization that came to haunt Martin’s imagination later on: atomic war, which he would write about in “Einstein’s Monsters” (1987), and the horrors of Stalin’s Russia, explored in “Koba the Dread” (2002) as well as in his gulag novel, “House of Meetings” (2006).

It is inconceivable though that Martin was not thinking. From the moment he saw those pictures of the gates at Auschwitz with the words “Arbeit Macht Frei” emblazoned over them at the age of five it is a fair bet his brain was abuzz. His luminous intellect (not all writers can brag about getting a “Congratulatory First” at Oxford — a rare distinction) and his capacity for white-hot moral outrage make his not thinking or caring about such issues hard to imagine. Even in the Pac Man arcades — perhaps especially there — he was ruminating about Auschwitz. A writer much admired by Amis, the German novelist W.G. Sebald, said, “no serious person ever thinks about anything else.”

England is snobbishly anti-Semitic. Royal Naval officers in the Portsmouth base where Christopher Hitchens was raised disparage Jews out loud with shameless alacrity, and London literati — like some in the Amis crowd — excoriate Israel. So it was a stunning moment when Hitchens learned that he was, in fact, ancestrally Jewish on his mother’s side, a family secret kept from him until he was well into his thirties. It changed him significantly, altered his ideas, and I believe had a profound effect on his best friend Martin. “There have been very significant Jews in my life,” Amis recently said. “Christopher Hitchens. Saul Bellow. My current wife. … It matters to me. It makes me more ‘inside history’ than I otherwise would be.”

“The Zone of Interest,” Martin Amis’s new novel to be released on Sept. 30, was born “inside” history. He has delivered a tragicomic moral blowtorch worthy of Swift. By turns, funny, disturbing and obscene, the book is set in KAT ZET, among the crematoria and gas chambers and the tea dances, piano recitals and petty office intrigues on an island of ultimate evil marooned in a gray Polish field, a new and hugely gutsy take on a topic you thought you “knew.” “The Zone” is of course the ramp where Jews arriving by train are selected for slavery or gas. “In the camp no-one knows themselves,” muses the monstrous commandant. “Then you come to the Zone of Interest, and it tells you who you are.”

If the book were a piece of music, it would be a sonata of interlocking monologues. Like some sinuous sax, we first hear the thoughts of Obersturmfuhrer Angelus (Golo) Thomsen. Untouchable as the nephew of Martin Bormann, Hitler’s sinister secretary, he idles around KAT ZET consulting with the I.G. Farben factory nearby where slaves are the labor. A compulsive womanizer with an “extensile penis classically compact in repose” as he proudly puts it, he has the hots for Hannah Doll, “country fed and built for procreation.” On one level “The Zone of Interest” is a love story set in the heart of Hades. Hannah is the wife of Paul Doll, the camp commandant and one of the great comic characters of modern fiction, whose self-described “meteoric rise through the custodial hierarchy” began at Dachau. His bombast suggests a big brass tuba. “Nobody can say that I don’t cut a pretty imposing figure on the ramp, chest out, with sturdy fists planted on jodhpured hips and the soles of my jackboots at least a meter apart.” As if to mitigate the loud sound made by these two terminally wicked windbags, we hear lastly the slow sonorous lament of a double bass.

Sonderkommandofuhrer Szmuel heads a Jewish crew chosen to help with the killing and the corpses. Fated to die in the end like all the others he describes himself as “the saddest man in the world… infinitely sad.” Meanwhile self-pitying Doll complains his job is hard. “How to make them burn, naked bodies, how to make them catch?” At one point Amis has Thomsen ask a fellow SS officer: “Would you agree that we couldn’t treat them any worse?”, to which his colleague replies, “Oh come on. We don’t eat them.”

Why write about Auschwitz? Has it not been vividly described in all its horror by Eli Wiesel and others? “I am returning to it,” Martin told a recent interviewer, “because … the Holocaust is going to absent itself from living memory in the very forseeable future.” He presumably felt he owed it to himself to make one more visit to hell and report back with a cliché-busting dispatch. However since he simply could not fathom Hitler’s depravity even after plowing through every book and interviewing every “expert,” he found himself stuck. For Amis it added up to writer’s block. It was Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi who rescued him. Near the end of his self-imposed quest to get to the bottom of the big Warum?, Amis stumbled across some words in Levi’s last book before his suicide that unlocked the riddle for him. “One must not understand what happened,” wrote the most morally eloquent of the Holocaust’s survivors. “Because to understand is almost to justify. … There is no rationality in the Nazi hatred; it is a hate that is not in us; it is outside man.” In other words, his childhood question to his mother has by definition no answer — and furthermore, must have none. With that mysterious insight, Martin felt liberated from his mental stasis and free to write this remarkable book — in my view, his finest so far.