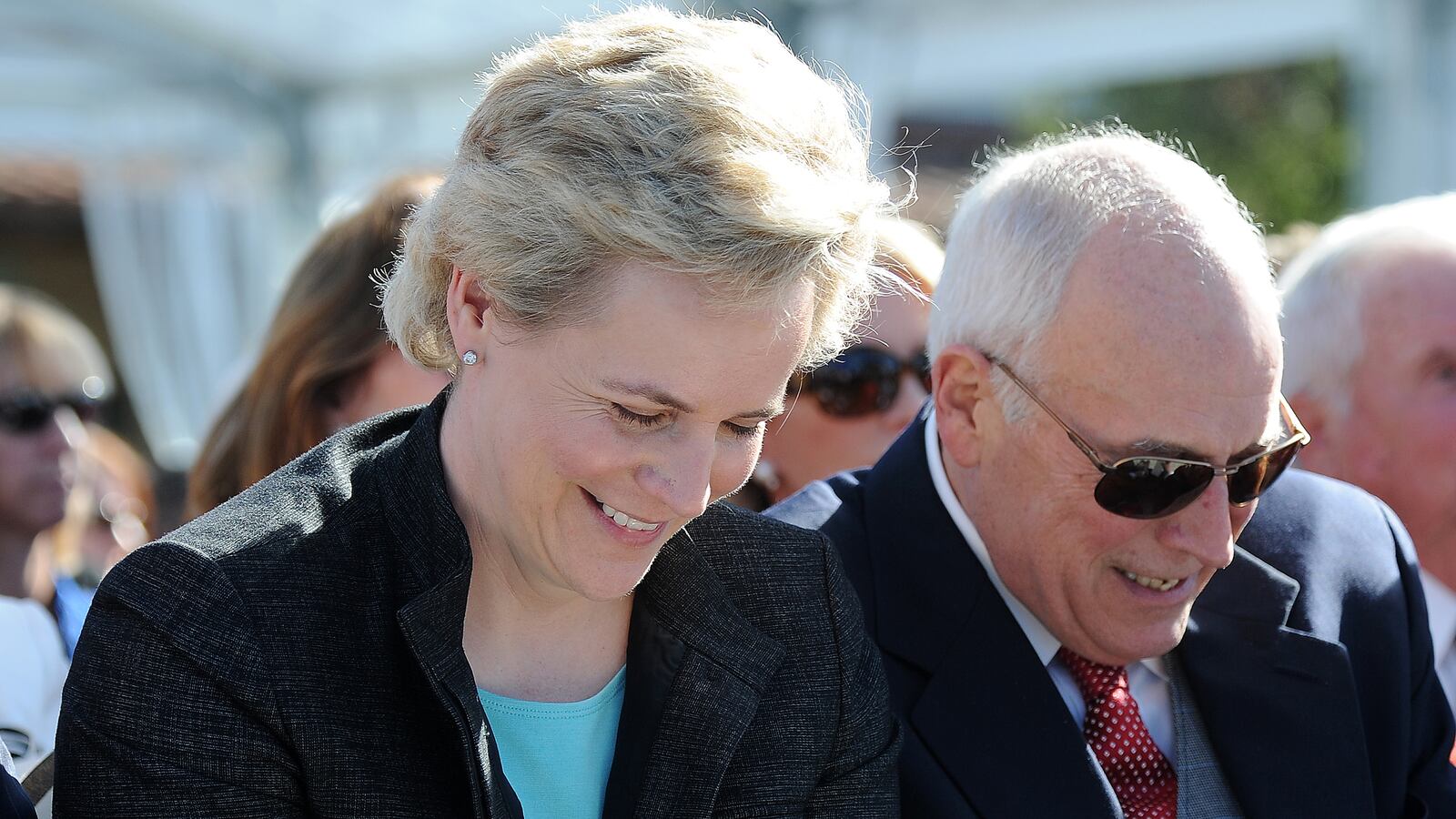

The fight between Liz and Mary Cheney over gay marriage is both sad and symbolic. It’s sad because they are thoughtful, caring, and conservative sisters who love each other, and the issue of gay marriage is driving a wedge between them—“big time.” Their fight is symbolic because the issue also is driving a wedge between the Republican Party and voters, especially young voters.

Many young Americans agree with Mary Cheney: Gay marriage is a fundamental right, and those who disagree are “on the wrong side of history.” Other voters are less strident in their support, but they think of themselves as tolerant people. They support civil unions. They enjoy reruns of Will & Grace. They enjoy being a part of the lives of their gay friends and family members. When they see people like Mary Cheney, her wife, Heather Poe, and their beautiful children, they see a family with value—even if they also believe that “marriage” is between a man and a woman.

Liz Cheney seems to be one of them, but that isn’t good enough for the far right wing of the party. They don’t like that Liz Cheney celebrates holidays with her sister’s family and has been a guest in their home. They don’t like that Cheney opposes a constitutional amendment to take the definition of marriage away from states and opposes laws that make it harder for gay Americans to visit their loved ones in a hospital, inherit their property, or adopt children.

Through the American Principles Fund, these extremists—the same kind of people who backed winners like Todd Akin and Christine O’Donnell—have spent a fortune in Wyoming running ads saying that Liz Cheney isn’t conservative enough. But what does it mean to be conservative enough? How extreme does a candidate need to sound in his or her tone and rhetoric to satisfy groups like the American Principles Fund?

The last thing on earth the Republican Party would brand itself as is “the party of gays.” And yet if it weren’t for gay and lesbian Republicans, who now make up an undefined but significant voting bloc, it is unlikely that Republicans would have the few electoral victories they’ve been able to celebrate this past decade.

A sudden flip on gay questions isn’t going to lead to a sea change at the polls among gay voters. But even if Republicans can’t win a majority of gay votes, they can stop shooting themselves in the foot with gay Americans and voters under 40.

In 2004, when President Bush narrowly defeated Democrat John Kerry, Bush did so with the support of 23 percent of gay voters, according to exit polls. In 2010, when Republicans retook control of the House, and John Boehner reclaimed the speaker’s gavel for the GOP, they did so with the support of 31 percent of gay voters.

No one knows exactly how many people in America are gay or lesbian—but it’s a number in the millions, and by some estimates, as many as 9 million. With that many self-identified voters, a population roughly the size of New Jersey, the gay vote is enough to affect a tight election, particularly in some key swing states such as Florida and Ohio.

The Democrats know this and are determined to turn the “gay vote” into a voting bloc as solid as the “black vote,” and, increasingly, the “Hispanic vote.” With significant prompting from the Democrats and their allies in the media, America’s attitude toward gay rights in general is changing dramatically. The Democrats are pushing for broader and more aggressive recognition of gays, while Republican leaders, cautious and conservative, appear increasingly out of step.

Consider that when NBA player Jason Collins came out as gay, he received immediate support from Bill Clinton and President Obama. Prominent Republicans were notably silent. Like it or not, it was a major moment in American culture. Comparatively, it wasn’t even that controversial: An ABC News/Washington Post poll found seven in 10 Americans support Collins’s decision to publicly disclose his sexuality.

The gay marriage question is making even more trouble for the GOP. A Pew Research Center survey just before the Supreme Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act found that nearly three-quarters of Americans—and a majority of gay-marriage opponents—think same-sex marriage is “inevitable.” Almost nine of every 10 respondents personally knew someone who was gay or lesbian, up from 61 percent in 1993. If voters perceive Republicans to be hostile to their friends or acquaintances who are gay, it could easily shape their entire outlook on the party.

There is even more cause for concern when looking at the numbers among young Republicans. According to a recent ABC News/Washington Post poll, a majority of Republicans under the age of 50 said same-sex marriage should be legal. Even former vice president Dick Cheney—perhaps the most conservative vice president since John C. Calhoun—came out in support of gay marriage, as did former first lady Laura Bush. Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) also shifted his position after his son revealed he was gay.

The growing view of a “gay-hating” GOP is taking its toll. The number of gays voting Republican, which had been rising for years, is now beginning to drop. In the 2012 election, exit polls showed that only 22 percent of gays supported Mitt Romney, a 9-point decline in the Republican vote since 2010. Overall, Obama held a more than three-to-one advantage in exit polls among voters who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

The GOP’s “traditional marriage” stance hurts it the most with voters under 40, particularly those between 18 and 29. By all accounts, young people should have flocked to the Republican ticket in the 2012 election, as they did in 1980 for Ronald Reagan and away from a recession-plagued Carter administration. Facing record unemployment close to 20 percent for their age cohort, they should have been lining up in droves to toss out an administration that made no headway in reducing youth employment and evinced even less interest in doing so.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Earlier this month, nearly half of gay-marriage supporters in New Jersey voted for Gov. Chris Christie, even though he does not support same-sex marriage. His election provides a model for other Republicans: Stand by your principled opposition to gay marriage but don’t alienate those who disagree with you. Romney didn’t need to traipse through DuPont Circle at the front of a gay pride parade, but he could have changed his tone when talking about gay issues. He could have been more welcoming of those with Republican principles regardless of their sexuality. And he could have castigated Republicans who preach intolerance.

Because Romney had a slew of other liabilities, low support from gay Americans and younger voters might not have cost Republicans the White House in 2012. But if we don’t change our tune, it might in 2016.