The president had won the election, but bitterness toward the press still consumed him. Less than two months after his landslide 49-state re-election, President Richard Nixon was lecturing his White House staff: “The Press is the Enemy. The Press is the Enemy. The Press is the Enemy.”

Tone comes from the top. Nixon’s senior staff followed their boss’s lead, adding 56 journalists and media executives to their infamous “enemies list.” There were attempts to intimidate through investigations and arrests; there were break-ins staged at private homes and offices. And in the case of the controversial investigative columnist Jack Anderson, Nixon’s operatives explored ways to murder the journalist via poison in his medicine cabinet or smearing LSD on the steering wheel of his car.

The role of the president and the press has been in tension since the earliest days of our republic. But during the Vietnam War, a new level of loathing poisoned the relationship between the White House and journalists in the fight over public opinion. It has never fully recovered.

Both Nixon and his Democratic predecessor Lyndon Johnson were infuriated by what they felt was unfair media coverage. The heated domestic debates over Vietnam had overturned decades of deference in press coverage of the president. The new technology of television broke down barriers that brought the reality of war into America’s living rooms, upending their assumption that journalists would almost uncritically support the president in times of war.

In the legion of great newspaper reporters who earned their stripes covering the war in Vietnam – David Halberstam, Neil Sheehan, Marguerite Higgins and Sydney Schanberg among them – the White House recognized that television correspondents had disproportionate power in the fight for hearts and minds at home.

When CBS correspondent Morley Safer captured images of American Marines lighting fire to thatched roof huts in a village believed to be harboring Viet Cong soldiers, Frank Stanton – the president of CBS News – awoke to a phone call from the president. “Frank, are you trying to fuck me?” Lyndon Johnson shouted. “Yesterday, your boys shat on the American flag.”

It likely became more difficult for Johnson to remain defiant when the iconic CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite returned from a week-long reporting trip to Vietnam and declared the war essentially unwinnable, upending months of false optimism from the administration.

When Richard Nixon rode to the White House proclaiming a “secret plan to win the war in Vietnam,” any expected honeymoon with the press did not last long. Popular opinion had firmly turned against the war and the “credibility gap” that bedeviled his predecessor grew into a chasm of his own making. Nixon was an accomplished geopolitical strategist with deep understanding of both politics and policy, but his hatred of the press would consume him and his presidency.

Nixon nursed his resentments and weaponized them with Machiavellian tactics. While directing attacks at the press from behind closed doors, he played the victim in public, rallying his conservative populist supporters against the media “elites” who dared to question his actions or motives. He wanted to destroy the credibility of the critical press. But Nixon had enough message discipline to have his dirty work done by others. He deployed his Vice President, Spiro Agnew, as an attack dog, targeting Vietnam War protestors and the media alike in pungent conservative populist terms. In one notable speech – Agnew would later resign in a corruption scandal – blamed the media for turning Americans against the increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam.

As Rick Perlstein recounted in his pitch-perfect history Nixonland: “Agnew told them the fault was not in the world, but in our networks.” It was they who “made ‘hunger’ and ‘black lung’ disease national issues overnight,” who “have done what no other medium could have done in terms of dramatizing the horror of war,” who were even responsible for the outrages of the Chicago convention: “Film of provocations of police that was available never saw the light of day, while the film of the police response which the protesters provoked was shown to millions.” Agnew said he wasn’t calling for “censorship.” But Walter Cronkite called it “an implied threat to freedom of speech.”

The problem, of course, was not the reporting. It was the steady stream of ugly facts on the ground and the result of cover-ups.

It took months for any news organization to pick up the horrifying report of American troops butchering Vietnamese women and children at My Lai after a military whistle-blower, Ronald Ridenhour, raised the red flag with an internal memo. Even then, it took a small news service called The Dispatch to publish the first accounts of the attack, giving larger news organizations the legal cover they felt they needed to proceed with account. Nixon ordered an investigation into leaked information about the My Lai massacre.

The Nixon Administration’s reluctance to come down hard on troops who killed Vietnamese civilians so infuriated a former Marine and Pentagon staffer named Daniel Ellsberg that he decided to Xerox 7,000 pages of an internal Defense Department history of the Vietnam War. When the New York Times published the first installment of what would become known as “The Pentagon Papers,” it showed that multiple presidents had lied to the American people about the prospects of success in Vietnam.

The downstream effect was disastrous. Nixon responded by suing the New York Times and launching an ill-fated assault on leaks – including a presidential-proposed break-in at the liberal-leaning Brookings Institution – executed by a shadowy group of staffers and hangers-on, known as “The Plumbers.”

The first amendment showdown in the Pentagon Papers case showed that the Nixon administration’s claim that the publication compromised national security was largely baseless, despite the high-stakes intimidation attempt of their action. In their 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court declared that the government had failed to meet the “heavy burden” to justify blocking the publication. They also set a high-standard for any future publication cases, determining that the disclosures would “surely result in direct, immediate and irreparable damage to our nation and its people.”

Arguably the more lasting legacy of the Pentagon Papers came directly from Nixon’s fury. He ordered presidential aides to destroy Ellsberg’s reputation – ironically, in the press. “I want to destroy him in the press. Is that clear?,” Nixon told his senior staff, kicking off a campaign of harassment that included a plot to assault Ellsberg at a protest and break into his psychiatrist’s office in a hunt for embarrassing information.

One year later, well on the way to a landslide in the summer of 1972, the same team of burglars deployed to break into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist were caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex.

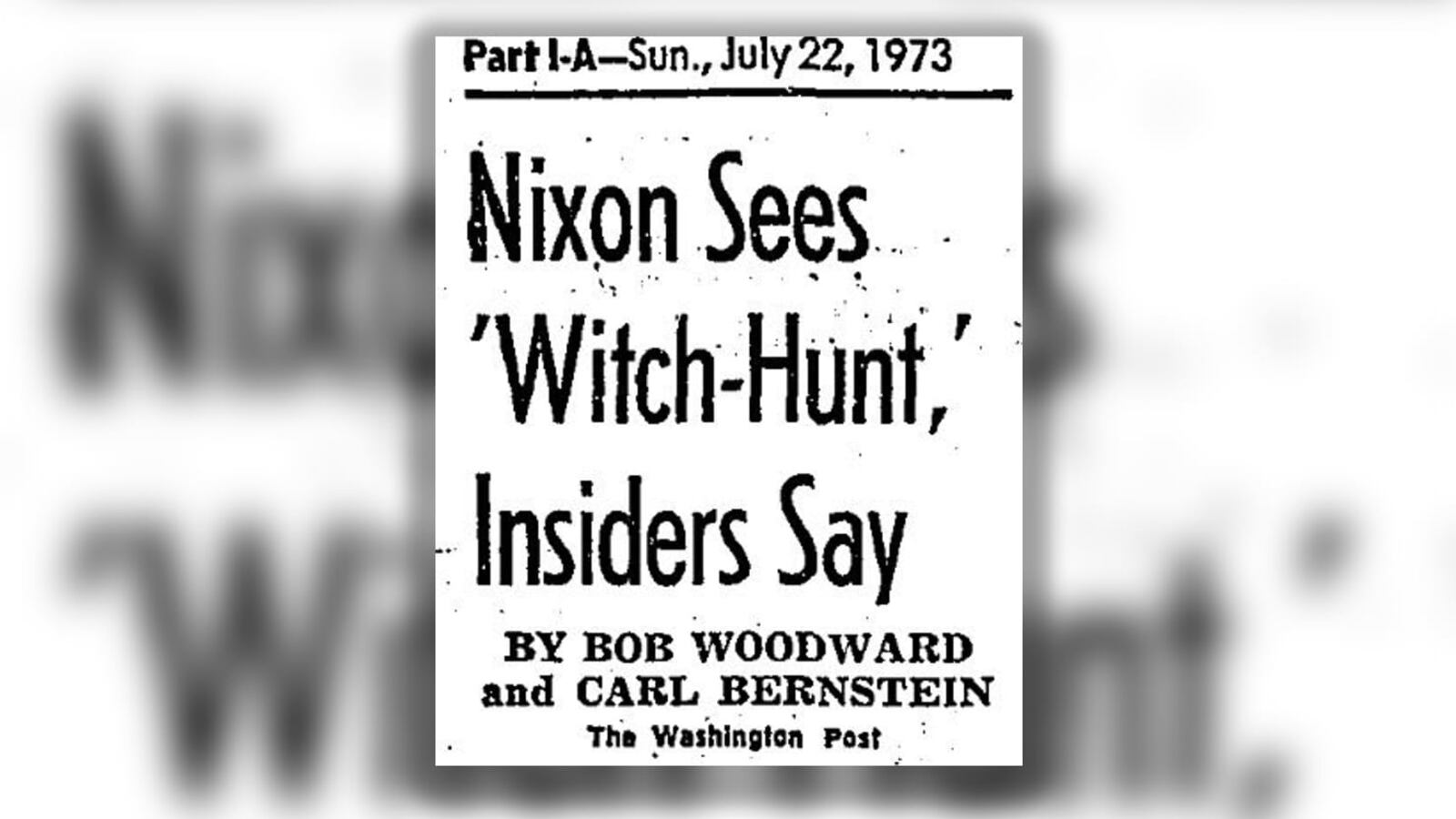

Two young Washington Post reporters assigned to the police beat, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, took up the investigation, facing accusations that they were politically motivated and making too much of what appeared to be a two-bit burglary that the American people did not care about. The Washington Post was attacked from the White House podium as being biased and threatened with lawsuits. President Nixon accused the investigation of being a “witch hunt.”

Over the next 18 months, Nixon would spur a constitutional crisis by firing a special prosecutor and ultimately resigned under Republican pressure as he prepared to face impeachment proceedings for obstruction of justice. Ultimately, his campaign manager and former attorney general as well as senior white house aides would receive prison sentences for their roles in the cover–up.

As Nixon and Agnew’s former speechwriter William Safire reflected from his post-White House perch as a New York Times columnist, President Nixon said “exactly what he meant: ‘The press is the enemy’ to be hated and beaten, and in that vein of vengeance that ran through his relationship with another power center, in his indulgence of his most combative and abrasive instincts against what he saw to be an unelected and unrepresentative elite, lay Nixon’s greatest personal and political weakness and the cause of his downfall.”

Or as Nixon himself said on the day of his resignation: “Always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don't win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”

Hear diverse perspectives from the war when PBS presents “The Vietnam War,” a new film from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Premieres Sunday, September 17, 2017 at 8/7c