All the recent debate about the future of Medicare is missing a fundamental truth: the odds of any major changes to Medicare are next to zero, no matter who wins this November. Oh, maybe there will be a little tweaking—some cost-cutting here and there, some minor reforms. But mark my words: nothing much is going to change.

Every 10 years or so, politicians attempt to mess with Medicare—and the public responds with a swift and clear “no.” Back in 1988, a Democratic Congress passed (by big margins) and a Republican president signed the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act, which called for substantial changes to Medicare. Sixteen months later, after a full-fledged revolt by seniors, the bill was repealed in the House by a vote of 360–66 and in the Senate by a vote of 99–0. It was the first time a major entitlement reform had been scrapped since President Roosevelt invented entitlement programs.

Then, in the winter of 1995–96, President Clinton and House Speaker Newt Gingrich came to a budget impasse over Medicare that led to a dramatic shutdown of the federal government. The episode was widely seen as a triumph for the defender of Medicare—President Clinton—who sailed to an easy reelection victory.

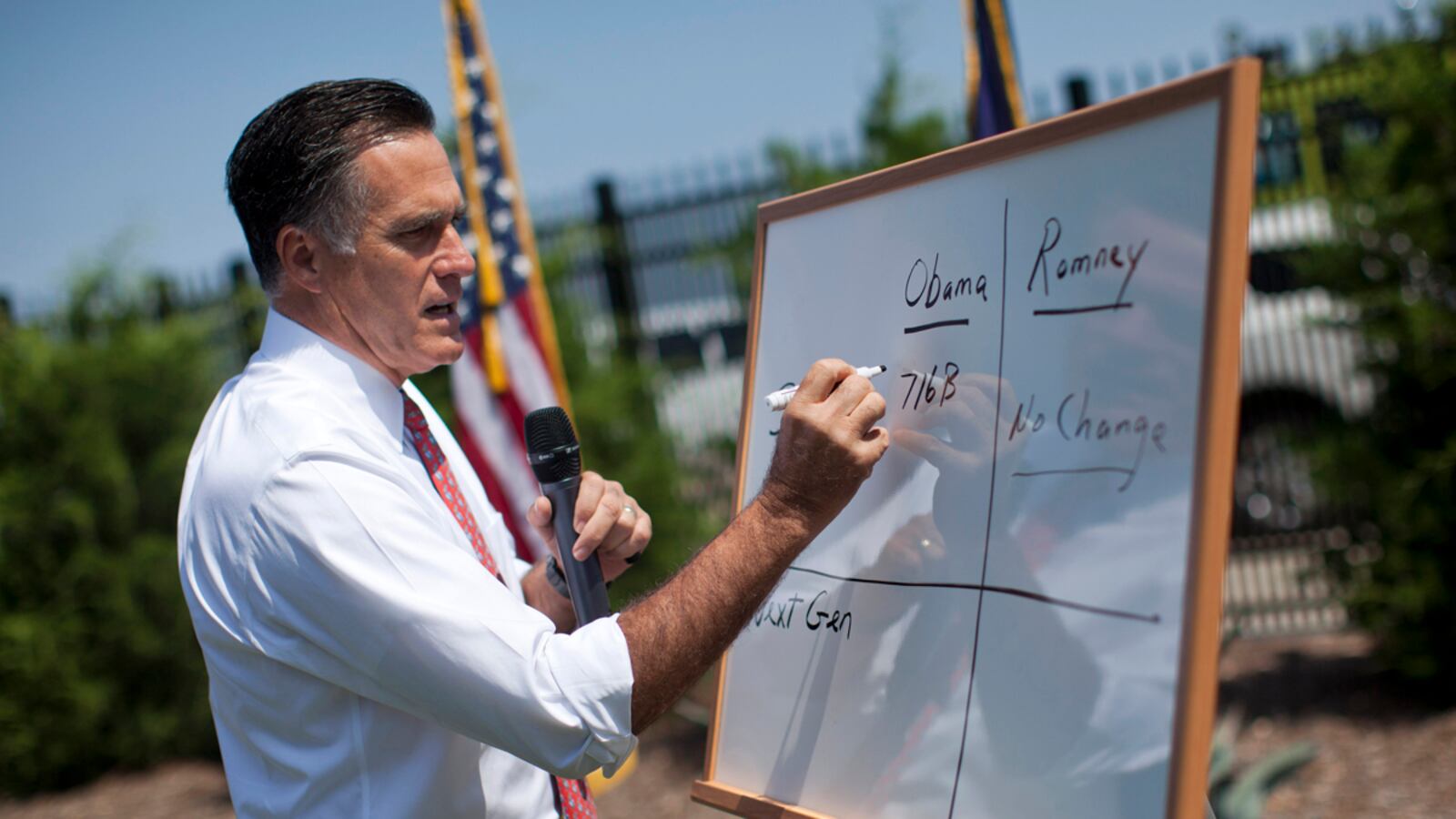

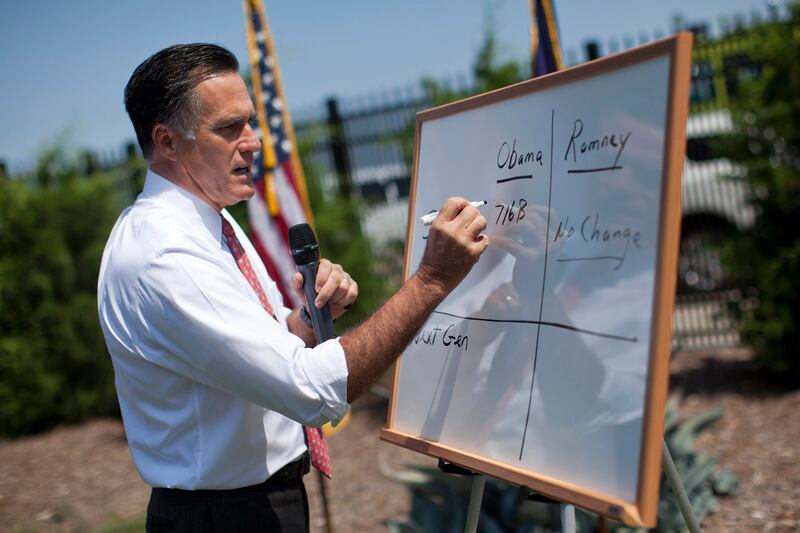

In 2010, President Obama did manage to push through major changes to Medicare, as part of the Affordable Care Act. But Republicans used this issue to help catapult themselves to victory in the 2010 midterm elections—once again illustrating that trying to reform Medicare comes at a steep political cost.

The current debate over Medicare is shaping up no differently. A recent Quinnipiac/New York Times/CBS poll of likely voters in the swing states of Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin found that 6 in 10 voters want Medicare to provide health insurance to older Americans “the way it does today.”

Why is Medicare so politically difficult to reform? It is not like, say, the Federal Reserve or sectarian conflict in Iraq—issues that most Americans, most of the time, don’t have direct interaction with or strong opinions about. Medicare is what keeps middle-aged people from having to go bankrupt when their elderly parents get sick. It allows people to save for college for their kids instead of saving for sickness in old age. It keeps the elderly independent longer. In short, Medicare is not a program for the elderly alone. It has enormous intergenerational benefits.

The most difficult thing to do in a democracy is to take away or fundamentally alter a longstanding benefit that almost everyone values. As the above items illustrate, a cursory reading of history shows that voters punish politicians who threaten Medicare. That’s why, come January, either President Obama or President Romney is going to decide that this is not a battle worth fighting.

Of course, that doesn’t mean Medicare doesn’t need to be reformed. I am not at all unsympathetic to the concerns of deficit hawks in both political parties. As someone who worked for President Clinton and Vice President Gore on a project to shrink the government, I understand the importance of fiscal discipline. But cutting Medicare is a lot tougher than cutting midnight basketball programs from the juvenile delinquency section of the Justice Department.

So what is to be done? James Pinkerton, a veteran of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush’s administrations, has been thinking outside the box on health care for a few years now. His idea is to switch the paradigm: have the government focus on curing the diseases that cost so much to treat. Take Alzheimer’s, for example. “[I]f AD is handled the way we handle many other diseases—with an emphasis on paying for it, as opposed to curing it—then we face fiscal calamity, as well as medical calamity,” writes Pinkerton. His argument is compelling: imagine if, 70 years ago, the government had been obsessed with funding iron lungs for all the children expected to get polio, instead of funding the research on vaccinations that led Dr. Jonas Salk to find the cure.

Voters will support federal dollars to cure the diseases that cost us so much. What they will not support, after all this time, is a fundamental change to Medicare.