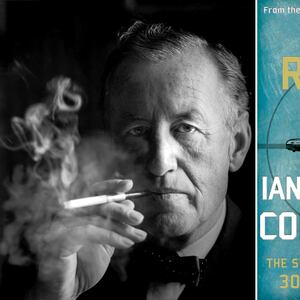

In 1946, seven years before the first James Bond novel was published, 007’s creator Ian Fleming built Goldeneye, a vacation home in Jamaica. Fleming was fascinated by the Caribbean island, with its history of seafaring, of pirates, of treasure lost and found.

One slip of land and sea that particularly obsessed him was the underwater ruins of Port Royal, the city once so notorious it was nicknamed the “wickedest city on earth.”

In Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born, historian Matthew Parker writes that Fleming, “was fascinated by the idea of the houses, brothels and bars of the buccaneers lying like buried treasure under the water nearby. On one visit he brought his snorkel, mask and flippers and swam down to inspect the old brickwork.”

Today, Port Royal is a small town known for fishing and the remnants of its British naval past. But during the second half of the 17th century, it was a thriving trade hub and port for the buccaneers who were first officially, and then unofficially, sanctioned to maraud and plunder on behalf of the British empire.

But its heyday only lasted 37 years. Around 11:40 a.m. on June 7, 1692, a vicious earthquake struck the southern coast of Jamaica; within minutes, two-thirds of the city that was built on a precarious spit of land slipped right under the sea where it can still be found today.

The settlers of Port Royal were asking for trouble—and not just because of their notoriously wicked ways. The city was established on the tip of what is basically a long sandbar known as the Palisadoes that juts out from the Kingston coast and winds its way through the harbor, providing something of a barrier for the capital.

While there is evidence that the indigenous Taíno people were familiar with the area, possibly using it as a fishing village, it was the British who first began to build a flourishing settlement on the unstable speck of land. By the time God’s proverbial lightning struck, Port Royal had become the second most populous city in the New World (losing the title to Boston).

According to UNESCO, around 2,000 buildings, many four stories tall, were packed into just over 50 acres of loose, sandy land and were filled by somewhere between 6,500 and 7,000 inhabitants (2,500 of whom were slaves).

One account of the thriving city from the 1670s succinctly sums up the state of affairs, describing Port Royal real estate as “dear-rented as if they stood in well-traded streets in London; yet it’s situation, is very unpleasant and uncommodious, having neither Earth, Wood, or Fresh-water, but only made up of a hot loose Sand.”

But who wants to worry about dubious feats of engineering or vulnerability to natural disasters when there are plundered riches flowing into town and plentiful taverns and brothels at which to spend it?

When the British conquered Jamaica in 1655, stealing it away from the Spanish, they chose Port Royal as a strategic defensive location. But finding the perfect plot of land on which to build forts wasn’t enough.

The British also needed muscle and their slim naval presence at the time wasn’t cutting it. So they did the next best thing: they invited the local piratical element to ply their nefarious trade on behalf of the British government.

The buccaneers were charged with harassing the Spanish (and French and Dutch) fleets, raiding rival colonial settlements, and bringing the riches back to their home base of Port Royal.

Even when the British naval forces became more plentiful, the buccaneers continued to raid and rob on behalf of the colonizers, effectively working side by side with sailors. Parker describes the arrangement as “state-licensed piracy.”

“The difference between the buccaneers and the English naval commanders, although [the latter] sometimes went rogue, is that the buccaneers did go rogue and they did perform these spectacular feats of basically murder and theft and robbery and arson,” Parker tells The Daily Beast, describing the “crossover” between the two groups. “I think we can’t see [the buccaneers] as entirely on the dark side because everyone was really on the dark side.”

The spoils of working on the dark side were irresistible. According to the BBC, one in every four establishments in Port Royal was a bar or brothel, and even though more “legitimate” tradesmen settled in town—goldsmiths and gunsmiths, sailmakers and hat makers, architects and cooks—everyone was enjoying the prosperity and debauchery established by the buccaneers and the wealth they brought.

“Almost every House hath a rich Cupboard of Plate which they carelessly expose, scarce shutting their doors in the night, being in no apprehension of Thieves for want of receivers,” Francis Hanson wrote in 1682.

It was thanks to the buccaneers that the economy of British-controlled Jamaica took off. Before the sugar plantations were established, the British were having a hard time getting their agricultural production up and running. Food was scarce and “they were starving,” Parker says.

It was the buccaneers who got money and riches flowing into the country via Port Royal.

But they also brought along scandalous behavior. The pirates were known to sweep into town and spend so much money in a single evening that they could be found on the streets begging by morning. Another favorite activity, according to Parker in The Sugar Barons, was to “buy a pipe of wine or a barrel of beer, place it in the street, and force all the onlookers at pistol point to drink.”

The town became “more rude and antic than ‘ere was Sodom,” wrote John Taylor.

In 1670, the government back in England tried to rein in the situation after signing a treaty with the Spanish. They pardoned the buccaneers and outlawed their official role in the defense of the colony; but until doomsday struck Port Royal in 1692, the pirates would continue to be tacitly accepted. The religious leaders who lived in town staffing the four churches and cathedral that neighbored over 100 taverns were beside themselves.

Reverend Emmanuel Heath was one of these. On the morning of June 7, 1962, he visited his church to say prayers “to keep up some shew of Religion among a most Ungodly Debauched People,” as he later wrote. Naturally, he then went to the bar.

He was presumably sharing a pint and commiserating with fellow citizens when the earthquake struck just before noon. Heath and his fellow tavern patrons walked outside and saw the “Earth open and swallow up a multitude of People, and the Sea mounting in upon us over the Fortifications.”

Port Royal was almost completely devastated in a tragedy that many in the following years would attribute to the judgement and wrath of God.

But it wasn’t divine intervention that caused the destruction; when the earthquake struck, much of the loose sand on which Port Royal was heavily built almost instantly liquefied. Two-thirds of the city simply slipped under the water, preserved in situ like Pompeii, exactly as it stood when the land began to shake.

But the end was not so peaceful for the residents who were home at the time. Around 2,000 of Port Royal’s citizens were killed in the initial disaster. Those who didn’t die instantly by drowning or falling debris faced an even more horrific demise as the earth began to re-solidify.

“Some inhabitants were swallowed up to the Neck, and then the Earth shut upon them; and squeezed them to death,” wrote Heath. An additional 2,000 inhabitants were killed in the following weeks by disease.

Attempts were made to rebuild Port Royal in the decades that followed. But as the pirates in the Caribbean became ever more bold as the British finally gave up their state-sponsored support, natural disaster continued to strike the city.

There were a series of earthquakes and fires throughout the 18th century. The British continued to run naval activities from the harbor port until the early 1900s.

Today, a small fraction of the city still stands, but it is what’s under the sea that continues to fascinate archaeologists (and at least one novelist). Under the water just off the end of the Palisadoes, there can be found part of a 17th-century town whose streets once plied by pirates are now the domain of fish.

“It makes a great story that it was the wickedest town in the world, but probably there were other places that were basically provisional cities or towns for the naval or merchant navy [that were just as bad],” Parker says. “But [Port Royal] got that reputation, I think partly because of what happened with the earthquake.”