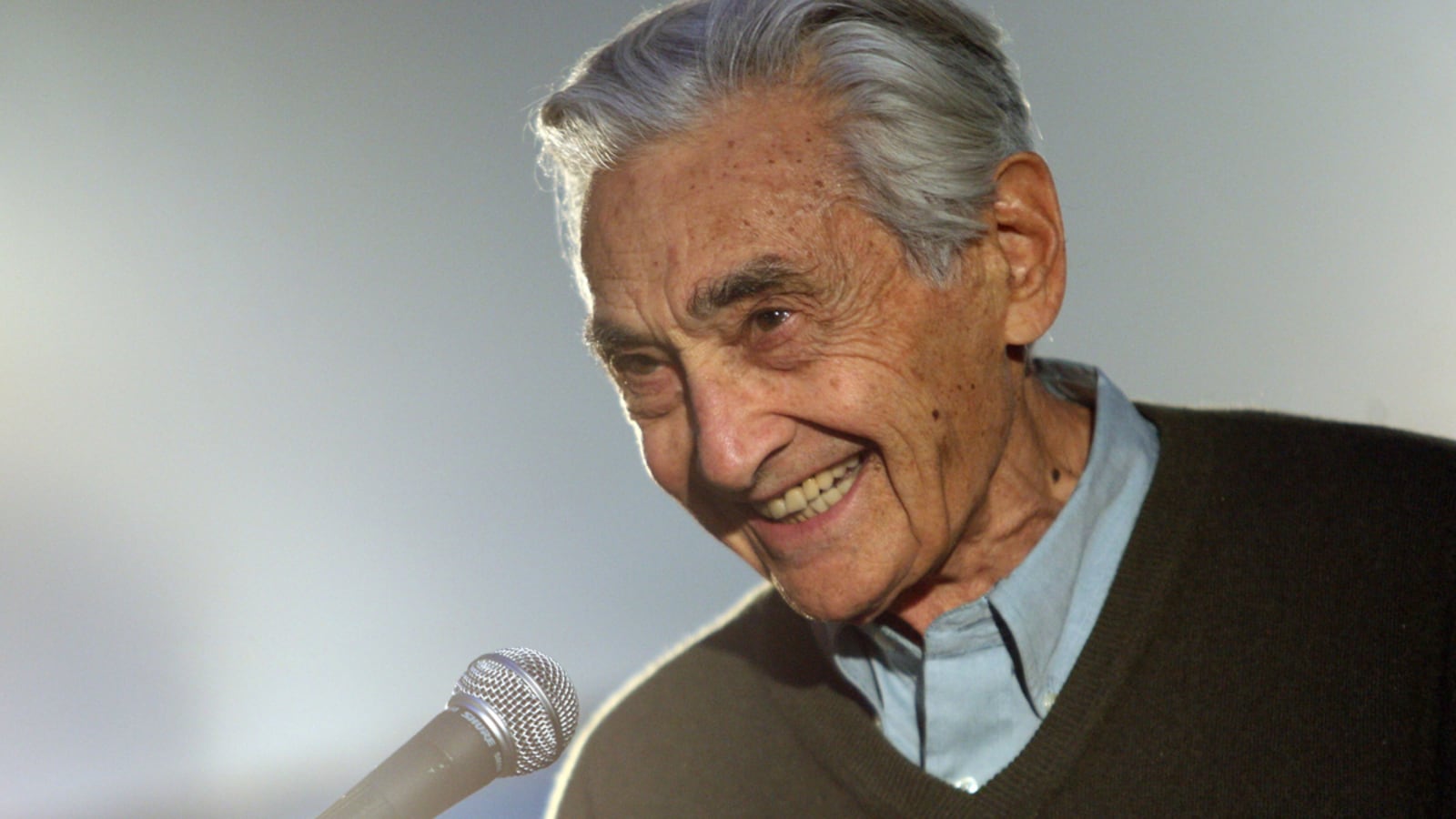

Howard Zinn would have been 90 years old on Aug. 24. Widely and affectionately known as “the people’s historian” during his lifetime, he was a prolific scholar and prodigious activist. To many of us, myself included, he was also a mentor and friend. He taught us all. Few historians write and make history, and for more than half a century, Howard Zinn did both.

Like so many young people of my generation, I first encountered Howard in the opening pages of A People’s History of the United States. The book did indeed knock me on my ass, as Matt Damon’s title character exclaims in the 1997 Oscar-winning film Good Will Hunting. Howard’s groundbreaking revisionist work was first published in 1980, just as the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s and 1970s was about to be steamrolled by the Reagan counterrevolution. I will never forget those opening paragraphs, unleashed without any introduction or warning:

Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the island’s beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts ...

These Arawaks of the Bahama Islands were much like Indians on the mainland, who were remarkable (European observers were to say again and again) for their hospitality, their belief in sharing. These traits did not stand out in the Europe of the Renaissance, dominated as it was by the religion of popes, the government of kings, the frenzy of money that marked Western civilization and its first messenger to the Americas, Christopher Columbus.

Here was Howard flipping the script on history, making it known that the narrative we had all been taught to revere and recite as schoolchildren—of Columbus’s “heroic” “discovery” of the so-called New World—could be told from a radically different point of view. Indeed, it must.

No one who reads the first chapter of A People’s History can miss the point: that this view of history, “a people’s history,” is the best antidote we have to the nationalist mythmaking that so often serves to justify the interests of the privileged and the powerful. And that’s the thing about Howard Zinn—he wore his politics on his sleeve. For him, history was not merely an investigation or illumination of some distant past, but also an intervention in the present for the sake of our collective future. “If history is to be creative,” Howard wrote, “to anticipate a possible future without denying the past, it should, I believe, emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even if in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together, occasionally to win.” At the core of Howard’s writing was a relentless critique of those who hold and abuse power, but also a stubborn optimism about the capacity of ordinary people to make history.

His optimism was firmly rooted in and shaped by his own life experiences. For Howard, the personal and political were always deeply intertwined with the historical. Born in Brooklyn in 1922 to hardworking Jewish immigrant parents, Howard was the product of a modest upbringing in which he was exposed early on to the everyday struggles of laboring people. As a young man coming of age during the Great Depression, Howard was deeply influenced by the protest literature of Charles Dickens, Upton Sinclair, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and John Steinbeck. When he was 18, he began working in a naval shipyard. In his celebrated memoir, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, he described this experience as “three years working on the docks, in the cold and heat, amid deafening noise and poisonous fumes, building battleships and landing ships in the early years of the Second World War.” In 1943, having just turned 21, he enlisted in the Air Force and flew bomber missions in Europe, an experience that would later lead him to question the morality of war. Indeed, his subsequent antiwar activism—which reached a fever pitch during the Vietnam era and continued through the contemporary wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—was deeply informed by the feelings of regret he had from being a bombardier. After the war, Howard went to New York University and Columbia University on the GI Bill (he liked to brag that he “never paid a cent” for his education). While a graduate student in American history, he worked the night shift in a warehouse and taught part-time day and evening classes at several nearby schools to make ends meet. Newly married, Howard lived with his wife, Roz, and two small children in a housing project in lower Manhattan while he wrote his Columbia dissertation, a well-regarded study of Fiorello LaGuardia, whose legendary congressional career during the 1910s and 1920s was, Howard argued, “an astonishingly accurate preview of the New Deal.” In 1956, before completing his doctorate, Howard secured a faculty position at Spelman College in Atlanta, where he taught a number of remarkable black women, including Alice Walker, the award-winning writer and activist, and Marian Wright (later Edelman), the founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund. His seven years at Spelman—he was fired for “insubordination” in 1963 because of his activism—coincided with the emergence of the black freedom struggle in the South. The rest, we might say, is history. Howard’s deep involvement with movement work inspired a lifelong commitment to civil rights and racial and socioeconomic justice. During the 1960s and 1970s, he was one of the leading voices of opposition to the Vietnam War; in 1967 he called for the “immediate withdrawal” of troops from Vietnam. From 1964 to his retirement in 1988, Howard was a professor of political science at Boston University, where he earned a reputation—richly deserved—as a beloved teacher, a prolific scholar, and first-class troublemaker.

Though Howard certainly had loyal defenders, including many of the leading intellectuals, artists, and activists of our time, his academic pursuits and political commitments also earned him harsh critics. One need only look at the 423 pages of his FBI files, released under the Freedom of Information Act in 2010, to understand what a threat he posed to the powers that be. An unapologetic radical, his civil rights and antiwar activism made him a prime target for federal surveillance, starting in the late 1940s, when the FBI sought to “obtain additional information concerning this subject’s membership in the Communist Party or concerning his activities in behalf of the party,” and continuing through at least the 1970s. (For the record, Howard always denied membership in the Communist Party and preferred to describe himself as “something of an anarchist, something of a socialist. Maybe a democratic socialist.”) His academic work, especially A People’s History of the United States, likewise attracted fierce opposition. In an article titled “The Left’s Blind Spot," historian Rick Shenkman, editor of the History News Network, indicted Howard for playing “the role in a self-satisfied often-uncritical mainstream culture of the seemingly attractive dangerous rebel.” Daniel J. Flynn, executive director of Accuracy in Academia, a conservative nonprofit that monitors college campuses because it “wants schools to return to their traditional mission—the quest for truth,” accused the “unreconstructed, anti-American Marxist Howard Zinn” of having a “captive mind long closed by ideology.” For Flynn, A People’s History was “little more than an 800-page libel against his country.”

Not all of Howard’s critics came from the right. In a searing critique published in Dissent in 2004, the distinguished social historian Michael Kazin wrote: “A People’s History is bad history, albeit gilded with virtuous intentions. Zinn reduces the past to a Manichean fable and makes no serious attempt to address the biggest question a leftist can ask about U.S. history: why have most Americans accepted the legitimacy of the capitalist republic in which they live?” The award-winning Columbia historian Eric Foner was more sympathetic. In his New York Times review of A People’s History, Foner praised Howard for “an enthusiasm rarely encountered in the leaden prose of academic history” and predicted that “historians may well view it as a step toward a coherent new version of American history.” Still, in a Nation tribute to Howard the week after his death, Foner also acknowledged that “[s]ometimes, to be sure, his account tended toward the Manichean, an oversimplified narrative of the battle between the forces of light and dark.” In a February 2010 New Yorker blog post titled “Zinn’s History,” Harvard historian Jill Lepore compared the experience of reading A People’s History in high school with reading J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye at the same age: “It’s swell and terrible and it feels like something has ended, because it has.”

While Foner and Lepore (though not Kazin) could forgive these limitations as perhaps a natural consequence of writing one of the first comprehensive “bottom up” social histories of the United States, others saw in Howard’s work clear evidence of ideological manipulation—or worse, political treason. In an article published the day after Howard’s death in January 2010, Ron Radosh, professor of history emeritus at the City University of New York, seemed to delight in dancing on Howard’s grave, writing, “Zinn ransacked the past to find alternative models for future struggles.” The right-wing pundit David Horowitz went even further the same day on National Public Radio, calling the book a “travesty” and arguing that “there is absolutely nothing in Howard Zinn’s intellectual output that is worthy of any kind of respect.” Two days later, concerned that NPR had edited his interview down to an inadequate sound bite, Horowitz used his blog to elaborate on his main point: “Zinn’s wretched tract, A People’s History of the United States, is worthless as history, and it is a national tragedy that so many Americans have fallen under its spell ... All Zinn’s writing was directed to one end: to indict his own country as an evil state and soften his countrymen up for the kill. Like his partner in crime, Noam Chomsky, Zinn’s life work was a pernicious influence on the young and ignorant, with destructive consequences for people everywhere.”

Truth be told, I am among the “young and ignorant” who have fallen prey to Howard’s “pernicious influence.” But I prefer to characterize myself, as Foner has elsewhere, as one of those “many excellent students of history” who “first had their passion for the past sparked by reading Howard Zinn.” The numbers, of course, speak for themselves. To date, A People’s History of the United States has sold upward of 2 million copies, making it the bestselling work of American history in American history. According to Hugh Van Dusen, Howard’s editor at HarperCollins, the book has increased its sales every year since its original publication in 1980, a trend that has only continued since his death. Writes Van Dusen: “I have never heard of another book, from any publisher, fiction or nonfiction, on any subject, of which that can be said—and I have asked a lot of people at other publishers whether they have heard of such a book.” There are many factors that have contributed to the runaway popularity of A People’s History: it was the first “bottom up” history of the United States; it embodied the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s while eschewing the reactionary soullessness of the Reagan counterrevolution; its lively narrative style served as a refreshing alternative to traditional academic scholarship; it articulated a bold point of view about the power of history; and it advanced a blistering critique of powerful people and institutions. More than anything else, however, it was a book that allowed so many Americans—workers and women, farmers and feminists, socialists and students, immigrants and indigenous people, communists and civil-rights activists—to see themselves as agents of history for the first time. The book is by no means perfect. In a later edition, Howard admitted that he “neglected groups in American society that had always been missing from orthodox histories,” including, crucially, Latinos and queer people. As an openly gay man, I remember talking to Howard about these omissions, and I appreciated his forthright acknowledgment that “my own sexual orientation ... accounted for my minimal treatment of the issue of gay and lesbian rights,” something he tried to make up for in the 1995 edition of the book. That was the thing about Howard—as with history, he saw himself as a work in progress. He was neither static nor set in his ways. As the title of his memoir suggests, though never neutral or “objective,” he was always on a moving train.

Howard’s critics—and there are many—have voiced three principal objections to his work. First, they accuse him of ideological extremism, of allowing his leftist politics to corrupt the more noble pursuit of historical “objectivity.” Second, they accuse him of oversimplification, of inverting “heroes” and “villains,” “winners” and “losers,” to construct a Manichean narrative of the American past. And third, they accuse him of celebrity, as if his entire career were driven more by the stroking of ego than the struggle for equality. Let me address each one of these criticisms in turn, beginning with the last.

In his later years, Howard was indeed something of a celebrity. Nothing helped to underscore this more forcefully than the scene in Good Will Hunting where Matt Damon’s working-class character invokes A People’s History. Following the film’s runaway success, Damon, who shared the 1997 Academy Award for best original screenplay with costar Ben Affleck, was determined to bring Howard’s bestselling book to the big screen. After Rupert Murdoch’s Twentieth Century Fox withdrew from a potential deal, Damon worked with Howard to get the film made through other channels, culminating in the 2009 History Channel documentary The People Speak, featuring an impressive list of A-list collaborators. Still, critics of Howard’s relatively recent “celebrity” miss several key points. First, Howard knew Damon when he was a young kid growing up in Cambridge, and their relationship predates either man’s celebrity. Second, Howard was infamous long before he was famous. One could easily make the case that his “celebrity,” such as it is, was forged not in the late-in-life embrace by liberal actors but in the relentless attacks of his conservative critics—from J. Edgar Hoover, who called him a “communist,” to Boston University president John Silber, who considered him a “menace.” If Howard became a media darling—and a lifetime of public caricature and criticism tends to constrain such a thesis—it is because he eventually earned a more favorable reputation by being on the right side of history for more than half a century. Finally, it is worth remembering that Howard spent half his life toiling away—as a worker, soldier, student, and adjunct instructor—in relative obscurity before he ever garnered any fame or fortune. He understood poverty because he came from it, and he appreciated the struggles of ordinary people because he was one of them. He may have achieved celebrity later in life, but he certainly didn’t start with or expect it.

The charge of oversimplification is a more credible criticism, one that we hear most often from professional historians committed to more traditional academic careers and credentials. Then again, as the radical historian Staughton Lynd, Howard’s friend and colleague during the early days at Spelman, has written, Howard was never principally concerned with impressing the academic elite: “The most remarkable thing about Howard as an academician was that he was always concerned to speak, not to other academicians, but to the general public. Soon after arriving in Atlanta, I asked him what papers he was preparing for which academic gatherings. This was what I supposed historians did. Howard looked at me as if I were speaking a foreign language. He was one of two adult supervisors to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and was preoccupied with the question of how racism may be overcome.” That said, Howard did indeed juxtapose the experiences of “the people” against the interests of “the powerful” in much of his writing. As Foner rightly acknowledged in his New York Times review, “[t]hose accustomed to the texts of an earlier generation, in which the rise of American democracy and the growth of national power were the embodiment of Progress, may be startled by Professor Zinn’s narrative. From the opening pages, an account of the ‘European invasion of the Indian settlements in the Americas,’ there is a reversal of perspective, a reshuffling of heroes and villains. The book bears the same relation to traditional texts as a photographic negative does to a print: the areas of darkness and light have been reversed.” Then again, the same could be said of much early revisionist social history, where scholars interested in African-American history, immigrant history, labor history, women’s history, social-movement history, and gay and lesbian history sought to expand traditional interpretations of the American past beyond the experiences and perspectives of wealthy, straight white men. As with much of Howard’s work, A People’s History amplified and synthesized the contributions of ordinary Americans who had been left out of more traditional histories. The book was meant to be transformative, not definitive, an opening salvo rather than the final word. Still, as Howard knew as well as anyone, those who break the mold are often criticized for doing so.

The loudest criticisms of Howard’s work, both his scholarship and his activism, come from his political detractors—some of them conventional liberals, others far more conservative. One could easily produce another entire anthology (or several!) of writings denouncing Howard for his “pessimism,” his “left-wing bias,” his “Marxism,” his “lack of patriotism,” you name it. That he was called everything in the book, however, does not diminish the importance or influence of the nearly 30 books he produced. The root of the problem is that Howard committed the worst of sins: he was a historian who rejected objectivity, an activist who refused to sit down and shut up, a soldier who hated war, and a citizen who dared to criticize his country. In other words, he understood—and insisted that we understand—that the denial of one’s politics is a politics of its own. Those who hated Howard did so because they couldn’t stand the fact that he was always forthcoming about his values and beliefs.

The audacity of Howard’s political honesty became evident to me the first time I invited him to be a guest lecturer in one of my Harvard courses, “American Protest Literature From Tom Paine to Tupac,” in the spring of 2002. I had asked him to come speak on the 1960s to help my undergraduates understand the connections between the civil-rights and antiwar movements. Though he certainly didn’t need one—his reputation far preceded him at that point—I gave him a glowing introduction. My students were thrilled to have him there, and he was eager to engage with them after his remarks. Unfortunately, word had gotten out about his visit, and we had a number of people in attendance that we had not invited to the class. I was keen to have this be a special experience for those enrolled in the course rather than a public event. When Howard finished his lecture, one of the uninvited visitors—a misanthropic graduate student who had already earned something of a reputation among undergraduates for being a crank—piped up with a question. Unceremoniously, he launched into a direct criticism of me, particularly my introduction, which he likened to a “coronation.” He ended his comments with this question: “Professor Zinn, don’t you think it’s irresponsible to display such overt politics in a classroom setting?” I was furious. Notwithstanding the fact that this graduate student had hogged the limited airtime reserved for my undergraduates, I felt that I had offered a sincere and gracious introduction, one that displayed my gratitude to Howard for his influence on me, as well as his generosity with my students. Before I could interject (a good thing, too), Howard smiled and responded with this gem: “No, I don’t think it’s irresponsible at all. Politics are in every classroom. As far as I’m concerned, my life has been devoted to rolling my little apple cart into the marketplace of ideas and hoping that I don’t get run over by a truck.” The students laughed. So did I. And Howard Zinn had made his point.

Though Howard was best known for his prolific writing and tireless activism, those of us who spent time with him beyond his more public persona knew him to be an exceedingly humble and generous man. The first time I met Howard, in the spring of 1999, I was still a graduate student. After defending my dissertation prospectus at Columbia, Howard’s alma mater, I moved back to Cambridge to become the guardian of a young man I had been mentoring since my days as an undergraduate at Harvard. This was a risky decision for me at that point in my graduate career. More than a few of my colleagues and professors warned that it would derail my “professional progress” (they were right, of course, but sometimes life gets in the way of one’s more selfish ambitions). I was lucky enough to secure a part-time teaching gig as a tutor in Harvard’s undergraduate program on history and literature, but I was still anxious about the daunting prospect of balancing dissertation writing with my new teaching and parenting duties. Whatever the reason, I sent Howard an email, totally out of the blue, asking if he’d be willing to have lunch with me. Having been radicalized at Columbia, I suppose I was looking for a suitable mentor who could stand in for Eric Foner and Manning Marable, my graduate advisers, while I was away. Within 48 hours, Howard responded with a date and time to meet at a favorite spot of his in Harvard Square. I brought my tattered first edition copy of A People’s History for him to sign, along with a bundle of nerves. Howard was, after all, something of a hero to me, but he owed me nothing. I worried that he would find me annoying or pathetic, or both. As it turned out, he was immediately disarming, listening carefully and patiently to my manic ramblings about history, politics, life, and graduate school. He was kind enough to affirm that there was room for yet another study of American abolitionism (my dissertation topic), and even kinder to affirm my decision to move back to Cambridge to help raise this young boy, to live life on my own terms. In retrospect, I was slightly embarrassed to have dominated the conversation so much, which made me even more grateful for his friendship that day. He even paid for my sandwich and iced tea. I left our lunch with a renewed sense of energy and purpose, as well as a deeper appreciation for the fact that some heroes have the capacity to be both human and humane. This was a vital lesson for me to learn at such an early age, and I haven’t forgotten it.

Over the years, our personal, professional, and political friendship deepened. Howard was a regular guest lecturer in my undergraduate course on “American Protest Literature,” and we spoke on several panels together. He helped John McMillian and me get our first book contract, for The Radical Reader, and then wrote a generous blurb. (It would be difficult to overstate how much that meant to us at such an early stage in our careers.) Over the years, Howard and I often found ourselves at the same protests and rallies—for a living wage, peace, and the like—and we were both cited by Lynn Cheney’s American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) for being “short on patriotism” because of our outspoken opposition to war in Afghanistan and later Iraq. In November 2001, when ACTA first published its report “Defending Civilization: How Our Universities Are Failing America and What Can Be Done About It”— which included a list of more than 100 “campus responses” in the wake of 9/11—I called Howard to joke with him about the fact that my protests had gotten me ranked No. 32, two spots higher than him. “Well,” he quipped, “it’s about time your generation stepped up.” Such laughter felt good, even liberating, especially during those dark times. As a young scholar-activist with no job security, I was comforted and strengthened to know that Howard was also on the front lines during a time when precious few Americans were willing to speak out against the accelerating pace of American imperialism in the first decade of this century. Then again, Howard was always on the front lines when and where it mattered.

As committed as Howard was to political activism—or perhaps because of it—he always found time for young people. Several years ago, I asked him to come speak to a group of students I was taking down South to help rebuild an African-American church that had been destroyed by arson. Each spring break for the past 15 years, I’ve organized trips like these, and they always inspire deep conversations about race, religion, civil rights, and social justice. In my effort to provide an opportunity for education and reflection on these issues, I thought Howard would be a great person to talk with my students about how this work connected to the long history of civil-rights activism in the United States. We settled on a Sunday afternoon, and I promised to buy him brunch beforehand. Howard was late to meet us; he had been trying to find parking in Harvard Square. After circling the block several times, he decided to park illegally. “A little civil disobedience never hurt anybody,” he joked as I introduced him to the student leaders of the trip. During brunch my students listened intently as Howard regaled them with stories of his involvement in the civil-rights movement, war and peace, history and activism, and his friendships with Alice Walker and Noam Chomsky. After brunch, we joined the rest of the group, and he spent nearly two hours talking with them, answering their questions, and posing for some photographs. As I was walking him to his car, I thanked him for his generosity and offered to pay for his parking ticket. “They never give me a ticket,” he said devilishly. Turns out he was right. If only they knew it was Howard Zinn’s car!

I share these stories to underscore several things about Howard’s character that too many of his critics never really seemed to take the time to understand or appreciate: his tireless commitment to teaching and mentoring, his uncommon generosity, and his quick wit. (The rebellious spirit, of course, is amply documented!) Another quality I came to cherish was his love for the arts. A playwright himself, Howard was also a patron of the arts. He regularly attended poetry readings, plays, films, and opera performances all over Boston. “Artists play a very special role in relation to social change,” Howard argued in a 2004 interview with alternative radio journalist David Barsamian. “I thought art gave them a special impetus through its inspiration and through its emotional effect that couldn’t be calculated. Social movements all through history have needed art in order to enhance what they do, in order to inspire people, in order to give them a vision, in order to bring them together, make them feel that they are part of a vibrant movement.” Howard, too, made us feel “part of a vibrant movement” by insisting that art, history, and activism could be each other’s muse. He believed this in his bones.

It is altogether fitting, then, that the last time I saw Howard—on Thursday, Jan. 7, 2010—was at a play. We were sitting in the front row of the Underground Railway Theater in Central Square in Cambridge. We had been asked to take part in a public humanities program to coincide with the production of Lydia R. Diamond’s stunning new play Harriet Jacobs, inspired by the 1861 slave narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. This was the first time the autobiography had been adapted for the stage, and Howard and I were both eager to take part in a series of events that would help bring the remarkable story of Harriet Jacobs’s life and escape from slavery to a broader audience. My colleague John Stauffer and I were slated to lead a postperformance talk-back with the audience on opening night; Howard was scheduled to do a similar event the next week. The play itself was brilliantly written and conceived, superbly staged and acted, and profoundly moving. During the lengthy standing ovation at the end of the performance, I remember worrying that I would have little to add to what was obviously a great triumph of the stage and of history. As John and I moved to take our seats in the middle of the black-box theater, Howard turned to me and apologized for having to leave early. He was not feeling well. I told him that I had been meaning to get in touch to invite him to speak again at Harvard, and he said that he would come do an event with me as soon as he was on the mend. Then he put on his coat, reached out his long arm, and squeezed my shoulder. “Carry on,” he said, before turning and exiting through the left-hand door at the back of the theater. Howard died three weeks later.

“Carry on.” Those words still haunt me. In retrospect, I suppose I should have seen then that he was very weak, showing his age like never before. I’d gotten so used to Howard being so strong, almost invincible, that I was incapable of imagining an alternative, to say nothing of the inevitable. What I wouldn’t do to go back in time, to have that moment once more, to hug him and thank him and make sure he knew that I, too, was part of that great democratic chorus that had found its voice—and its roots—because of his life. That’s the thing about death: we never get a second chance. Howard knew that, and he lived accordingly. The people’s historian may be gone, but there is more history to write and more history to make. It is our turn now to do what he taught us to do: “Carry on.”