Some time ago, I made a basic decision about the way in which I was going to live the little of life available to me. The idea was to place myself in the presence of only those people who give off the warm, friendly vibrations which soothe the coating on my nerves. Life never was long enough to provide time for enemies. Nor is it long enough for people who bore me, or for me to stand around boring and antagonizing others, or for all of us, the others and me, to get into these half-friendly, half-sour fender-bumpings of egos and personalities and ideas, a process which turns a day into a contest when it really should be a series of hours serving your pleasure.

So I gave up jobs which made me uncomfortable. I wrote a book and sold it for a movie without seeing one person involved. I began avoiding any bar or restaurant where there was the slightest chance of people becoming picky and arguing. I reduced conversation, even on the telephone, to the people I like and who like me. One night, my wife had a group of people for dinner and I was not sure of the vibrations around me at the table so I said, “Excuse me, I have to go to bed. I have paresis.” It worked wonderfully. I began to do things like this all the time and I wound up doing only what I liked when I liked doing it and always with the people I liked and who liked me.

“Do you want to go out to dinner tonight?” my wife asked me.

“Where?” I said.

“Well, I don’t know. We’ll go with my sister and her husband.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t think he had a good time with us last week and he might be a little cold tonight. I’m afraid he might strip my nerves. I’d rather just stay home.”

“All right,” she said.

So we stayed home. During the night I said hello on the telephone to Jerry Finkelstein, Jack O’Neill, Burton Roberts and Thomas Rand. We all talked nice to each other and I could feel the coating on my nerves being stroked and soothed. On Sunday I went into the office in my house and I spoke to nobody and saw nobody all day. So it was one of the most terrific weekends.

The first phone call on Monday morning was at seven o’clock.

“He’s asleep,” I heard my wife mumble.

“Wake him up?” she mumbled.

She kicked me and I reached over for the phone.

“Somebody named Joe Ferris,” she said. “He needs your correct voting registration for the petitions. What petitions?”

I sat up in bed, with the phone in one hand and my head against the wall and my eyes closed.

“What petitions?” my wife said again.

I knew what petitions Joe Ferris was talking about. I knew about them, but I never thought it would come to the point of an early morning phone call about them. You see, when it started, I was only in this thing for pleasant conversation with nice people. “Hello,” I said to Joe Ferris. I was afraid he would send cold waves through the phone.

“I’ve got to be at the printer with the petitions this morning,” Joe Ferris said. “So what I need is the exact way your name and address appears on the voting rolls. We don’t want to have any petitions thrown out on a technicality. Because they’re going to be looking for mistakes. Particularly when they see how much support you and Norman are going to get. That’s all I’ve been hearing around town. You and Norman. I think you’ve got a tremendous chance.”

“I’ll get the information and call you back,” I said to Joe Ferris. He gave me his phone number and I told him I was writing it down, but I wasn’t. Maybe if I forgot his number and never called him back, he wouldn’t bother to call me anymore.

“What petitions?” my wife said when I hung up.

“Nothing,” I said. I put my face in the pillow. Well, to tell you what happened. I really don’t know what happened, but I was in a place called the Abbey Tavern on Third Avenue and 26th Street at four o’clock one afternoon, when it was empty and I wouldn’t have to talk to anybody I didn’t know, and Jack Newfield came in. Jack Newfield is a political writer. He writes for the Village Voice and Life magazine and he does books and we got to know and like each other during the Bobby Kennedy campaigns last spring. Anyway, I’m having coffee with Jack Newfield and he says, “Did you hear me on the radio the other night? I endorsed you. I endorsed Norman Mailer for mayor and you for president of the City Council in the Democratic primary.” I did two things. I laughed. Then I sipped the coffee. While I did it, I was saying to myself, “Why is Mailer on the top of the ticket?”

And a couple of days later, I had lunch in Limerick’s, on Second Avenue and 32nd Street, and here was Newfield and Gloria Steinem, and she likes me and I like her, and Peter Maas, and he is all right with me, too, and we got to talking some more and they kept saying Norman Mailer and I should run in the Democratic primary and finally I said, “Has anybody talked to Norman?”

“No, not recently,” Gloria said.

“Give me a dime,” I said.

I went to the phone and called Norman. While I was dialing, I began to compromise myself. Norman went to college, I thought. Maybe it’s only right that he’s the mayor and I’m the president of the City Council. But that’s the only reason. He has a Harvard diploma. On ability, I should be mayor.

“Norman?”

“Jimmy, how are you?”

“Norman, let’s run.”

“I know, they spoke to me. But I have to clean up some business first. I think we could make a great team. Now here’s what I’m doing. I’m going to Provincetown for a week to think this over. Maybe we can get together for a night before I go. Then when I come back, we can make up our minds.”

“All right,” I said.

So two nights later there were about 40 people in the top floor of Mailer’s house in Brooklyn Heights. They were talking about the terrible condition the city was in, and of the incredible group of candidates the Democrats had in the mayoralty primary, which is on June 17. Norman Mailer began to talk about the right and the left mixing their flames together and forming a great coalition of orange flame with a hot center and I looked out the window at the harbor, down at a brightly lit freighter sitting in the black water under the window, and I was uneasy about Mailer’s political theories. I was uncertain of the vibrations. Then I turned around and said something about there being nine candidates for mayor and if New York tradition was upheld, the one who got in front in the race would be indicted. When I saw Norman Mailer laughing at what I said I decided that he was very smart at politics. When I saw the others laugh, I felt my nerves purring.

Then he began to talk casually, as if everybody knew it and had been discussing it for weeks, about there being no such thing as integration and that the only way things could improve would be with a black community governing itself. “We need a black mayor,” Mailer said. “I’ll be the white mayor and they have to elect a black mayor for themselves. Just give them the money and the power and let them run themselves. We have no right to talk to these people anymore. We lost that a long time ago. They don’t want us. The only thing white people have done for the blacks is betray them.”

There hasn’t been a person with the ability to say this in my time in this city. I began to think a little harder about the prospects of Mailer and me running the city.

We had another night at Mailer’s, with a smaller group, and he brought up the idea of a “Sweet Sunday,” one day a month in which everything in the city is brought to a halt so human beings can rest and talk to each other and the air can purify itself. When he got onto the idea of New York taking the steps to become a state, he had me all the way. The business of running this city is done by lobster peddlers from Monauk and old Republicans from Niagara Falls and some Midwesterners-come-to-Washington-with-great-old-Dick such as the preposterous George Romney. I didn’t know what would come out of these couple of nights, but I knew we had talked about more things than most of these people running in the Democratic primary had thought of in their lives.

Mailer was leaving for Provincetown the next morning, and we agreed to talk on the phone in a few days.

I stayed around the city and somewhere in here I had a drink with Hugh Carey. He is a congressman from Brooklyn and he is listed as a candidate for mayor. I told Carey I was proud the way he turned down a chance to make a lot of headlines with an investigation into the case of Willie Smith, a poverty worker in New York who had been convicted of great crimes in the newspapers. Carey announced that Willie Smith not only was clear, but also was doing a fine job for the poor. Endorsing the poor is not a very good way of getting votes these days. So I thanked Carey.

“What did you want me to do?” Hugh Carey said.

“Well, I just wanted you to know,” I said.

“I wish to God I’d been right on the war when I should have been,” he said. He had, from 1965 until only a short time ago, been a Brooklyn Irish Catholic Hawk, of which there are no talons sharper. But now he could look at you over a drink and tell you openly that he had been wrong. “It’s the one thing in my life I’m ashamed of,” he said. “And I’m going to go in and tell every mother in this city that I was wrong and that we’re wasting their sons.”

Pretty good, I thought. Let’s have another drink.

“How’s it look for you?” I asked.

“Well, it’s up to The Wag,” he said.

“The Wag?” I said.

“The Wag. Bob Wagner.”

“What the hell has he got to do with it?”

“Look, if he comes back and runs and I can get on the ticket with him, then in a year he’ll run for the Senate against Goodell and I can take over the city and we’ll start putting the type of people in…”

Well, I told him then what I’m putting down here now. If Robert Wagner, who spent 12 years in City Hall as the representative of everybody in New York except the people who had to live in the city while he let it creak and sag, if this dumpy, narrow man named Robert Wagner, by merely considering stepping back into politics, could have a Hugh Carey thinking about running on the ticket below him, then there was something I didn’t like about Hugh Carey. Not as a guy, but as a politician who would run a city which is as wounded and tormented as New York.

You see, the condition of the City of New York at this time reminds me of the middleweight champion fight between the late Marcel Cerdan and Tony Zale. Zale was old and doing it from memory and Cerdan was a bustling, sort of classy alley fighter and Cerdan went to the body in the first round and never brought his punches up. At the start of each round, when you looked at Zale’s face, you saw only this proud, fierce man. There were no marks to show what was happening. But Tony Zale was coming apart from the punches that did not leave any marks and at the end of the eleventh round Tony was along the ropes and Cerdan stepped back and Tony crumbled and he was on the floor, looking out into the night air, his face unmarked, his body dead, his career gone. In New York today, the face of the city, Manhattan, is proud and glittering. But Manhattan is not the city. New York really is a sprawl of neighborhoods, which pile into one another. And it is down in the neighborhoods, down in the schools that are in the neighborhoods, where this city is cut and slashed and bleeding from someplace deep inside. The South Bronx is gone. East New York and Brownsville are gone. Jamaica is up for grabs. The largest public education system in the world may be gone already. The air we breathe is so bad that on a warm day the city is a big Donora. In Manhattan, the lights seem brighter and the theatre crowds swirl through the streets and the girls swing in and out of office buildings in packs and it is all splendor and nobody sees the body punches that are going to make the city sag to its knees one day so very soon. The last thing, then, that New York can afford at this time is a politician thinking in normal politicians’ terms.

The city is beyond that. The City of New York either gets an imagination, or the city dies.

A day or so after seeing Carey, I came into Toots Shor’s on the late side of the afternoon, when the place is between shifts—empty. Paul Screvane was finishing lunch. He was sitting with Shor. I tried a cautious drink. The vibrations among the three of us were all right. I settled down to talk with them. For weeks, Screvane had wanted to announce his candidacy for mayor. But he had been waiting until he heard what Wagner was going to do.

“Why wait?” I said.

“Well, because all the financial support I normally would get would go to Wagner,” Screvane said.

“Well, what’s he going to do?” I asked.

“I’ve called him for a week. I’m waiting to hear from him right now,” Screvane said.

“He’s next door in the 21 Club. He knows I’m here. I’ll just wait.”

Screvane waited. He waited while Wagner came out of the 21, walked slowly down the sidewalk to Shor’s, stopped and chatted with somebody in front of Shor’s, nodded to Shor’s doorman, probably looked through the doors and saw Screvane inside, and then ambled off.

“That’s a real nice guy,” I said to Screvane.

He said nothing. A few minutes later, the headwaiter handed him the phone. Screvane came back muttering, “Wagner just had his secretary call me. ‘Where will you be at seven and at nine tonight in case Mr. Wagner wants to get in touch with you?’ How do you like that?”

“Why don’t you just say the hell with this guy and go ahead and announce you’re in it?” I said.

Shor slapped his hand on the table. “Go ahead,” he said.

“The hell with it,” Screvane said. He got up and went to the phone. He came back smiling. “All right, I called my secretary and told her to start calling the papers and television for a press conference tomorrow morning at eleven o’clock.”

“Terrific,” I said.

“Are you going to be there?” Screvane said.

“Absolutely,” I said.

Well, what happened was, I walked out of the place feeling so good about Paul Screvane standing up and not letting somebody push him around, and this is the way it should be because Screvane is a tough, extremely competent man and nobody should try to take advantage of him. Well, I felt so good about all of this that two hours later I called up Norman Mailer and I said, “Norman, the hell with it. Let’s make up our minds right now.”

“We’re doing it,” he said.

The Village Voice promptly came out with pictures of Mailer and myself on the front page. The type underneath the pictures said that we were “thinking” of running for office.

I don’t know about the rest of the paper’s circulation, but I know of two people who looked at the front page very closely.

One was Paul Screvane.

The other was my wife. “This is a joke, of course,” she said.

“Oh, sure,” I said.

“Well, if you’re that sick for publicity,” she said.

There were a couple of calls at the house in the next day or so and my wife handled them, although not too well. “The publicity stunt is tying up our phones,” she said. “I don’t want these phones tied up. I have real-estate people calling me from the Hamptons. We’re going away on a vacation this year. We haven’t had one in three years.”

“Uh huh,” I said. I was looking over the messages she had taken during the day. One was from Gloria Steinem. I knew what that was about. She had a meeting scheduled with some good, young Puerto Rican guys who were interested in politics and wanted to see what Mailer and I looked like. There would be no warm, friendly vibrations from them. These guys would snarl and snap a little, particularly if I said something stupid. So what? I’d learn something from them while I was at it.

So now here we come to this one morning, and this is how I got into what I am into, and I am in bed with my face in the pillows and I am trying very hard to forget Joe Ferris’ phone number, and the phone rings again and my wife answers it.

“Yes,” she says.

“Oh, I don’t know if he’s doing that.”

“You know that he’s doing that? How do you know?”

“Gloria Steinem said what?

“You’re going to write a story? Here, you better talk to him.”

She handed me the phone. “This is Sarah Davidson from the Boston Globe and she is going to write a nice big story for the first page about you and Mailer running for office. Tell her to make sure she puts in that you’re a dirty bastard.”

I take the phone and I say hello to Sarah Davidson. A gentle, restrained, cautious politician’s hello.

“Sarah, dear, how are you, baby? When are we going to get together for a drink?”

Ten minutes later, the call that makes the whole thing official comes.

“Gabe Pressman,” my wife muttered.

“Oh, he’s just a friend of mine, you know,” I said.

“Hello, Gabe, how are you, baby?” I said.

“Running? Well, we have been talking about it. You know what I mean, Gabe. How many times did we speak about this over a drink? You know how thin the talent is in this city. Look at the names, Scheuer. He says he’s going to spend a million dollars for his primary campaign. Well, let me tell you, Gabe. Scheuer has to spend a million-two, just to get known in his own neighborhood. And look at these other guys. Mario Procaccino. How do you like it? How do you like the Democratic party going with Mario Procaccino for mayor in an election? Mario for waiter, yes. For mayor? Good Lord. And the guys they got running in my column, the City Council president, hell, we can’t afford to have a thing like this.

“Wagner? Forget Wagner. He’s an old man. He won’t win a primary.”

“Shut up,” my wife said.

I held the phone away. “Hey, what are you telling me to shut up for?”

“I said shut up,” she said.

I went back to the phone. “Lindsay? Gabe, you know better than I do that Lindsay came into this city like a commuter. He doesn’t…”

“Shut up,” she said again.

“What do you mean, shut up?” I said.

“Because he’s going to put down what you say and make you sound like a sour dope.”

“What do you mean? Gabe and I are good friends.”

“You’re not supposed to give long answers to a reporter,” she said. “You’re going to make yourself look like a jerk and the whole family is going to suffer because of it.”

I’m holding the phone against the pillow so Gabe Pressman won’t hear.

“Hey, this is a friend of mine calling up. It isn’t like an interview. This is personal.”

“No it isn’t. He’ll put down everything you say. He’s unethical.”

“What do you mean he’s unethical? Gabe Pressman is not. He’s a friend.”

“Hey,” she said, “all reporters are unethical. Who knows better than you? You wrote the book.”

I made a date to meet Pressman and a camera crew at noon. When I hung up, the phone rang immediately. It was Alice Krakauer, who is handling the scheduling for our college appearances. She told me to write down a date for City College. While I was doing this, my wife got up, got dressed and went out of the bedroom. She called up to me from the front door. “I’m going with my sister to look at houses. We’ll be back tomorrow. When I come back, if the phone rings once with this business, I’ll have to ask you to leave.”

She left. I got up and started for the subway. At the newsstand, the woman said, “Don’t I see your picture some place? Are you running for something?”

I stood there and thought for a moment. Thought very deeply. Newsstand Dealer for Mailer and Breslin! My right hand shot out so fast the woman nearly fell over backwards.

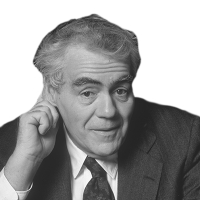

“Hi, I’m Jimmy Breslin,” I said to her.