We bought the old farmhouse a decade ago, when we were a new family, buoyed on that promiscuous hope peculiar to young couples: everything will be all right as long as we have each other. And to not have each other was inconceivable. So when I heard the whispers about the woman who sold us the house—her husband met someone online, leaving her with their 5-year-old and a court order to sell their home, such a shame—I thought it must have something to do with her, this person whose desperate anger roiled the very air of the bank’s closing room. I was in the presence of something so dark and disheveled it repelled me, and I found its manifestation in the garden the next week: a chaos of weeds that, pulled apart, revealed stunted annuals planted in the promise of spring but now forgotten, all but dead. Who would allow things to come to this? I sniffed.

Six years later, it was me sobbing through the exchange of papers and checks in the same room. I understood now, suddenly and quite well. My garden had gone untended for months. Its heedless growth in directions I had not planned stood for the terrible waywardness of everything I had once thought predictable. A relentless carousel started revolving in my mind; if only I could find the explanation for what had happened, the infernal thing would stop and I would finally have some peace, finally eat again and sleep. One night I believed I had caught the ring at last: it was the house itself that had delivered to me and our 7-year-old the identical fate I had so sanctimoniously dismissed years before.

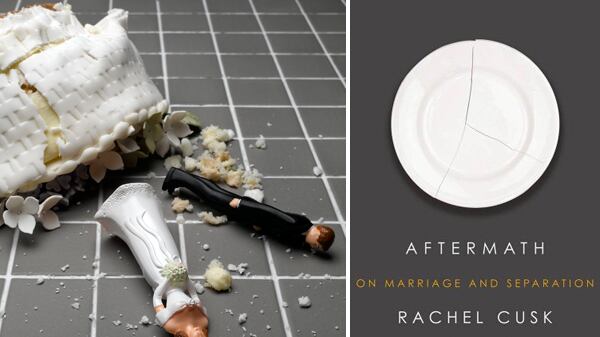

It was not the house. But the garden still represents something in the world-eating passage that is divorce: I met it again in Aftermath, the British writer Rachel Cusk’s brutal evocation of her divorce. “Lately our garden had become overgrown. The beds were drowning in weeds. The grass was long, like hair.”

Divorce is the mother of metaphor. It cannot be met head-on; describing that which it is like offers the only chance to grasp it. Alone, raw, it is a broken egg that drips through your fingers. (See? There I go again.) My own metaphor for destroyed marriage was the two-masted schooner suddenly requiring one to mind tiller and wheel, run up the sails and read the charts, all at once. Hence an impossibility whose only result could be insanity. For Cusk, it is “a jigsaw dismantled into a heap of broken-edged pieces.”

However it is imagined, it remains one of a few seminal events in life that perfectly cleave the world in two: either you are inside, or out. Either you have experienced its shuddering immensity, or it is still invisible, the crevasse that reveals its depths only after you have fallen in and now wait for the smack that signals bottom. It resembles childbirth, except that when you have a baby you climb, toward a peak obscured by clouds. All you know is that it is apparently endless, a walk of miseries and wonderments admixed.

Cusk took on the mountain first, in 2001’s A Life’s Work. I read it shortly after I, too, had had a child, and doing so was like finally letting go of a breath I had held for a year. Ostentatiously smart, fearless, the author displayed what almost seemed a compulsion to yank the threads of that impossibly pretty doily tatted by convention around motherhood. Of the common advice to “get in touch” with one’s unborn baby, she rejoins, “As my stomach gets bigger I realize that getting in touch with it is about as useful as a field getting in touch with the motorway being built through it.” No sentimental muck here; she forthrightly observes those minute sensations we dismiss as insignificant but are in fact the only truth we have.

Her memoir of divorce displays the same ferocity of intellect, humor, and occasional bad mood. Sometimes, it seems, this woman is simply in a nasty frame of mind. Her litany of complaint and fault-finding (“The blackness of hate flows and flows over me, unimpeded”) becomes tiresome, but so did my own to me over the first year when its whirlpool circled endlessly, reluctant to go down the pipes. Reading Aftermath is like having a flashback to the freakish experience of living through your own death.

Here we go, deep into the vertiginous spiral where the author seeks understanding of something that in its nature resists comprehension: good for phenomenology, not so good for narrative. Cusk knows this, of course; she is of the cerebral breed that is used to thinking their way out of any situation. “If someone were to ask me what disaster this was that had befallen my life, I might ask if they wanted the story or the truth.” Divorce, however, is no philosophical or literary construct: it is an animal one. It is not reeled back into painlessness if only your reconsideration of The Oresteia is especially brilliant, or if the poetry of your description of the bizarrely changed everyday (visit to the dentist, first attempts at dating, search for a nanny) is notably transcendent. That these all appear unhappily transformed does not mean the new world order is a profoundly broken one. Aftermath acutely demonstrates, however, that for a long while it certainly feels that way.

A long, long while, for some: Sharon Olds’s poem cycle Stag’s Leap (forthcoming from Knopf) covers many years during which she was stuck in the undried glue of love for the husband who left. PTSD in verse form, the poems consider, in a stunned tone, what was lost from every angle. “And at a party, or in any crowd, years / after he has left, there will come an almost / visible image of my husband… “ One awaits the poem describing a first date in vain; just for a change, it would have been a relief to glimpse someone else’s “cindery lichen / skin between the male breasts.” After all, it is the momentous “first date post-” that represents both our humanity in all its dunderheadedness—we don’t learn too well from our mistakes, eh?—and the vows we take with life itself, from which love is indivisible.

To the consummate writer (as Cusk spectacularly is), events like divorce issue a challenge: Own me, comprehend me—write me! The first year after my separation was spent feverishly endeavoring exactly that. “Oh, good,” friends said; “this will help you work through the trauma.” No, I thought, that’s what my therapist is for. I know the difference between “working through” and “making literature.”

It turned out I knew nothing of the sort. Only after I read another divorce memoir, Suzanne Finnamore’s Split, did I feel deep gratitude for my editor’s failing verdict on what I thought would be my own metaphysics of divorce: the lava had not yet cooled. Finnamore—who had also written about motherhood, making the two of them possibly the only authors of Nutshell Libraries for the Fifty Percent—waited years before approaching the subject that when fresh is simply too molten.

It is a testament to Cusk’s talent that she was able to make something of it that would not set fire to the reader, only raise the occasional blister; it was she, the newly divorced, who was rendered ash. That is how it always is. But sometimes a phoenix rises. Sometimes the bird takes the shape of a book.