The esteemed actor Gabriel Byrne is a wonderful storyteller; truly you could listen to him for hours. A “Gabriel Byrne Story Hour” to send us off to sleep would be just as effective as Golden Girls re-runs.

It is why our audience listened, utterly rapt, as he recited stories from his life in his one-man autobiographical play, Walking With Ghosts, which opens tonight at Broadway’s Music Box Theatre (through December 30). But some of the stories Byrne tells us, as beautifully distilled and performed from his bestselling memoir as they are, also feel not fully told. They touch on serious subjects, and things that have reverberated in his life—but the deeper ones feel too glancing in the telling. Unlike perhaps the full book, the stage show feels like a peekaboo exercise in memoir, and the reticence, or self-editing, or whatever it is, ill serves some of the material.

Directed by Lonny Price with apposite delicacy, Byrne—who won a Golden Globe for his role in In Treatment—takes us through slices of his life, seeing himself until the very end as a “ghost boy” progressing through times and incidents. The best moments of the play are suited to precise, close-ended moments in time. And then there is Byrne’s lyrical writing. As he begins the play: “So here I stand on a grey Dublin day, looking at the house we called home for so many years. The man I am now longing to see the world as a child again, when every sight and sound was a marvel. I can see myself, a ghost boy, running among the trees, and along by the river, past the chapel, the cinema, the factory, and up to the fields where the plough horses turned the black earth to the sun.”

He has an author’s eye for detail. Of one adult he recalls from his youth, he notes, “She always wore black, and a locket at her throat that had hairs from her dead husband’s mustache inside. She wore an eyepatch over one eye and her other eye rolled around like a big marble.” A Mrs. Woods is remembered “leaning on her gate with her new teeth like a row of fridges.”

Byrne remembers his mother taking him to a posh afternoon tea at a hotel; he quotes her precisely, a small portrayal of escapism in a life where she never felt fulfilled. “Would you look at the little tongs they have for putting the sugar in the tea,” the mother says to her son. “Pure silver. Look on the back, you can see the mark. That’s how you know. You can always tell the good thing. O this is the life. Isn't it lovely to have a day free?”

He recalls the delight of spending time with his grandma, from where his love of cinema sprang. “Every time I stayed with Granny, we went to the pictures and for dinner we had a big bowl of cornflakes. Soon the characters on the screen were as familiar as real people, and Granny would talk back to them.”

Byrne tells these stories on a relatively unadorned stage. There is a table, some chairs, a kind of scored background. They are mini-portraits of a life, vignettes charmingly told. Because of his skills as an actor and writer, they sometimes rise to the level of poetry. The loveliest moment of the play comes in the second act, when Byrne recalls his journey into acting, after a short stint in the construction industry, via local amateur dramatics—the productions, characters, and the pubs full of camaraderie; the mugging of how to do a double-take, triple-take, and quadruple-take.

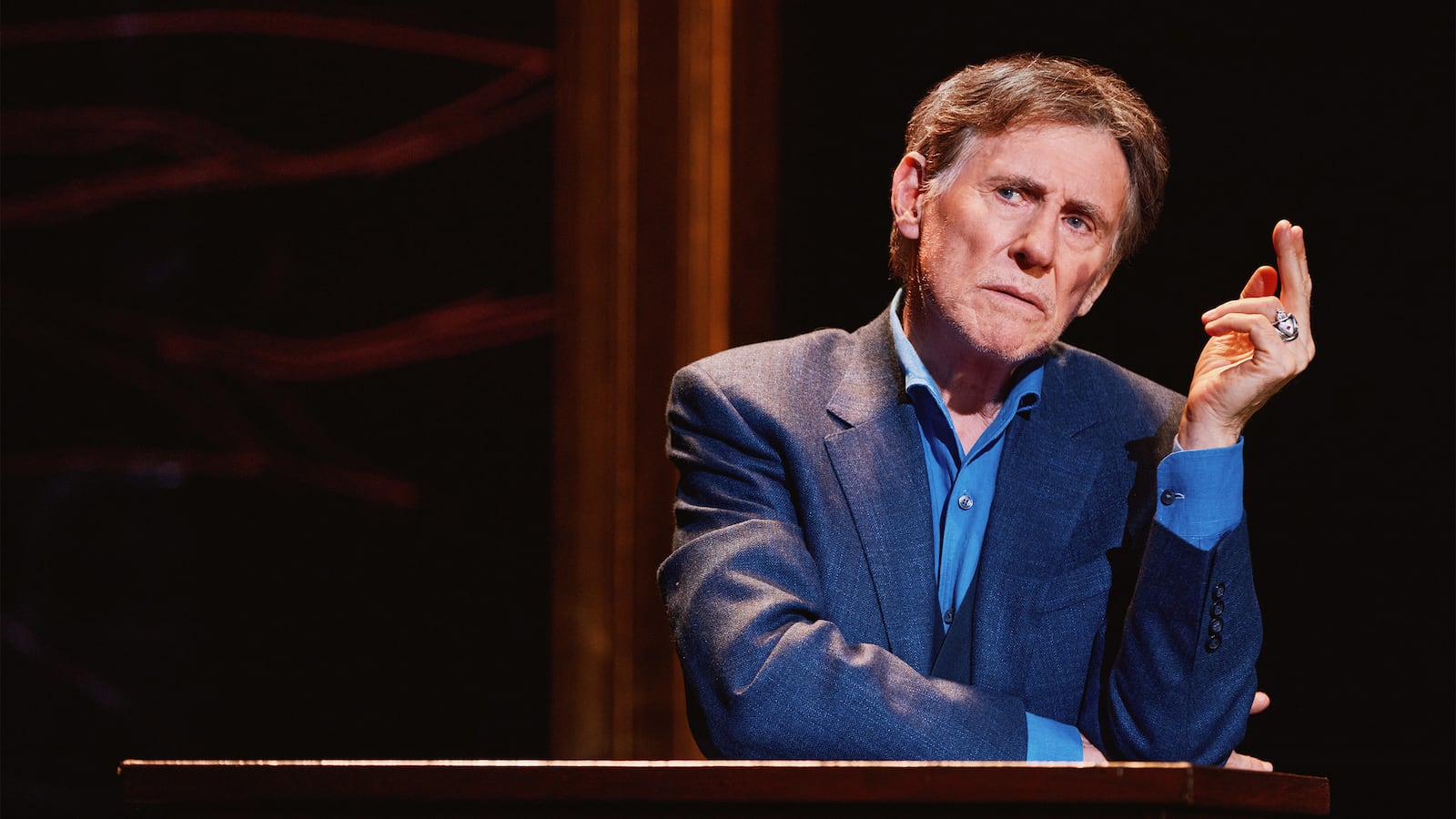

Gabriel Byrne in “Walking With Ghosts.”

Emilio MadridAt the end of this slalom of pure narrative pleasure came this critic’s first frustration. What happened after his first flush of success with an Irish soap opera? How did fame come? How did his career grow? All is left untold. Instead, we are told of the time he was excited to get a role that gave him just one line—“This way, please”—which he tried to endow with more scene-stealing drama than it merited. It’s hilariously related, but again the fuller story eludes us. Still, there is a lovely anecdote of going from penury to filming—and drinking—in a glamorous hotel with Richard Burton.

Byrne also tells us in graphic detail about the abuse he endured at the hands of a priest as a boy. “There was a rip in the side of my trousers from where I’d been roughhousing in the gym. When he put his hand into the tear I was mortified that he’d know I wasn’t wearing underwear. His breath was sour and hot as he moved toward me. Then there was blackness.” Again, this is beautiful writing, but what happened next? How did he come through the experience of the abuse? What presence or not did it exert in his adult life? Is it just a story to be told, or did its scars run deeper?

Byrne speaks of a mentally ill sister. “A clamp was set between her teeth, electrodes on her temples. A switch was clicked. Her body shuddered and jerked violently as the electricity coursed through her.” The detail again is perfect, and the delivery is searing and deeply felt. But questions again recur: What was the cause of the illness, what happened next?

His experience of alcoholism is more fully expanded upon. “The first time I became aware of alcohol it was Christmas morning. I was 8 years old, it was whiskey in a glass on top of the piano. The firelight shone in the yellow liquid.” However, what was lying beneath this addiction? Were there demons, or terrible things, at the root of it? Whatever, “I was tired of slashing my own soul, and I was sick of the roaring life.”

The writing is lovely, but incomplete and frustratingly partial, when more complete story arcs or detail are required given the import of what has been discussed. Time is likely against this, but such are the perils of putting a memoir on stage. Byrne is divulging very personal things, but his deepest confessions raise questions that go unaddressed—on stage at least. Perhaps they are in the memoir, but we shouldn’t have to know the memoir to see the stage show, or to fill in its gaps. Too often you are left thinking: Why did you do that? What caused this? There is a convincing intimacy to Walking With Ghosts, but that intimacy is also slightly deceptive. Byrne keeps us close and also at arm’s length.

Still, an evening of seductive storytelling ends in the smooth spirit of the whole, with Byrne speaking about his parents. It is moving and funny. Byrne recalls taking his dad out for a fancy dinner, now that he’s a successful actor. “You did well for yourself, you’re in the films,” his dad says. “You’re as well known as Doran’s donkey. But I thought you would have stuck at the old plumbing game.”

Then, when he sees the check, his dad exclaims, “Seventeen pounds. Lord Jaysus. At least when Dick Turpin robbed people, he had the courtesy to wear a mask.”