“Because I deal in extremes,” utters Brian De Palma, “I always get extreme reactions.”

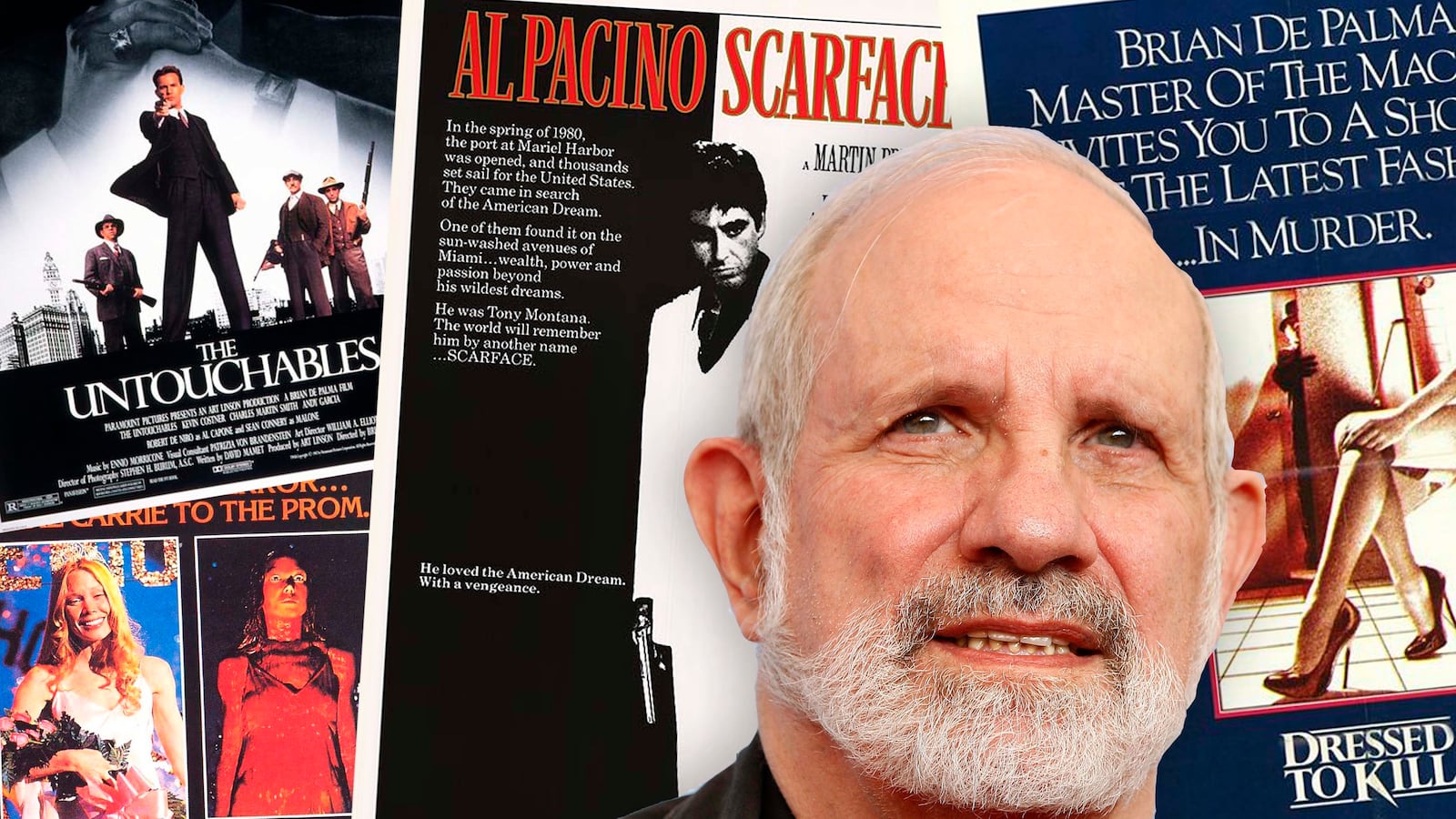

He ain’t kidding. Despite birthing a host of celebrated films, including Carrie, Scarface, and The Untouchables, and receiving heaps of praise from the late New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, who likened him to his “New Hollywood” contemporaries Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, De Palma remains arguably the most polarizing filmmaker in cinema history. He’s been nominated for 5 Razzie Awards for Worst Director—the most ever—and has sparked furious debates about cinema artistry and violence. His thriller Dressed to Kill was even branded “a master work of misogyny” by Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media.

In this writer’s mind, however, De Palma is often misunderstood. He artfully combined the psychological suspense of Hitchcock with the operatic gore of Argento, and like Tarantino, is a remix-artist of the first order, from the 360-degree shot in Blow Out to the Notorious-esque staircase shot in Scarface to The Untouchables’ Odessa Steps sequence. His split-screens, strident scores, and long Steadicam shots all amplify the moviegoing experience, not diminish it.

“You’re reviewed against the fashion of the day, and when the fashion changes—as it has on many of my movies—and they live forty years later, they’re something that transcends the fashion of the day,” he says.

The 75-year-old director is the subject of De Palma, a new documentary by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow. It basically consists of De Palma analyzing and deconstructing his past movies, and provides a fascinating peek at one of cinema’s most intriguing filmmakers.

The Daily Beast sat down with De Palma in New York to discuss his storied career.

One anecdote I found fascinating in De Palma is that perhaps your most autobiographical character is Keith Gordon’s nerd in Dressed to Kill.

Keith had played me in Home Movies, so I wrote this character into Dressed to Kill. But I’d build computers as a teenager and won a couple of science fairs in high school.

And like Gordon’s character, you engaged in a voyeuristic hunt of your own when your mother tasked you with trailing your father in order to catch him in an affair.

I was in a difficult situation. My mother was very unhappy, and she charged me with following my father when I was about 16. I would never do it of my own volition. It was very odd. I was acting as a surrogate for my mother, basically. She wanted to get out of this marriage, and I was the catalyst that got her out of it.

Did that experience of watching—observing—your father’s affair at such an early age inform your interest in voyeurism?

Maybe. It’s a basic tool of cinema, watching something. We watch things through a camera, follow people, use point-of-view shots, we girl-watch. I’m always very interested in what are the most basic elements of cinema that make it different from other art forms, and the most stunning thing is that what you see is the same thing as the character sees. This observing is something I use quite a lot.

Another experience you had as a teen was regularly watching your father perform surgeries on patients. I imagine those images were hard to shake. When you grow up in a hospital, believe me—and I used to watch my father operate, I used to hang out with the interns and the orthopedic residents summer after summer. I saw a lot of blood. I saw people die, people in terrible pain, limbs being cut off. I saw my father saw off a leg. Tremendous amount of blood. There’s a leg, take it away. My father was a carpenter almost in a sense of, hey son, this is the job. But images are powerful. War coverage drives me crazy because the images we saw out of Vietnam, you see nothing like that today. If you’re dropping a bomb and killing people, or your army is over there doing horrendous things, you’ve got to see what they’re doing.

You don’t get enough credit for a lot of things, but one of the things you really don’t get enough credit for is discovering Robert De Niro, who made his first film appearance in your 1969 movie The Wedding Party—which was shot in ’63.

No question. He auditioned for The Wedding Party, this movie I made out of graduate school, and I cast him. That absolutely happened. It was the spring of ‘62 that I first cast Bob out of the Sarah Lawrence acting program. Bob just came in to read for one of the groomsmen, and Bill Finley was playing one of the other groomsmen in the room. Wilford [Leach], who’s a great theater director and won two Tonys, looked at each other and said, “This guy’s really good.” Then he said, “I want to show you something,” and he went out of the room. This was over at a loft around 6th Street and Broadway, and it’s 6 p.m. He comes back in and is ranting and raving. He’s doing a scene from Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty. Before, he was a funny comic, and here he was showing this incredible power in this impassioned speech. We were blown away. Needless to say, he had the part before he left the room.

You’re also credited with introducing De Niro and Scorsese. I believe you’re even given a “special thanks” in the credits of Mean Streets for it.

Marty [Scorsese] and Bob were introduced at a party at Jay Cocks’—a Time film critic who’s now one of Marty’s screenwriters. I believe that’s where Bob and Scorsese met for the very first time. I took a class at NYU film school for two semesters, and I saw him there because he was already a bit of a star, and we started to hang out, especially when he was working on Woodstock. That’s how that particular group got together.

It’s the 40th anniversary of Carrie, and one of the things I never knew about the film until seeing the documentary is that you shared casting with Star Wars, so you and George Lucas were looking at a lot of the same young actors for your films.

We shared an office and looked at every young person that came through. Amy Irving was almost Princess Leia, and you can see her audition online, but she ended up in Carrie. We saw every young actor in New York and L.A.

Now, Carrie has been remade a few times and none of them have worked. Do you have any control over this?

Exactly. I know Kimberly Peirce, because I used to hang out with her and she talked to me while she was making it. But… I don’t know. I was in the right place at the right time with the right cast, never to be done again. It was the first commercial film I had, and the first one in the studio system.

Back to Star Wars. You will forever be a part of Star Wars lore, and it’s probably all Peter Biskind’s fault. In his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, he wrote about how you gave some harsh criticism to George Lucas after a test screening of the first Star Wars movie.

That’s right. It wasn’t really a “test screening,” but just for friends. I was there, Steven [Spielberg] was there. Jay Cocks and I rewrote the scrawl at the beginning of the movie, because the first one we saw, you didn’t know what the hell was happening in the movie. Jay was a film critic at the time so he and I fixed it up so it made some kind of sense.

But you didn’t like that cut of Star Wars, right? No! That’s completely wrong. I have a caustic, sarcastic wit, and if people ask me about something I’m going to tell them the truth. We were there to tell George what we thought, and what we thought didn’t work. But we were knocked out by this movie.

Steven Spielberg seemed to be the most knocked out. I read that he and George Lucas made a bet on the set of Close Encounters where they basically swapped points because each thought the other’s movie would do better. And Spielberg has made over $40 million from Star Wars.

Yes, that’s true. It’s all true. They switched points. There was no question that everybody thought it was great. There was nobody saying, “This is a catastrophe.” That’s ridiculous, and nobody should ever be given that impression. It was a rough cut, so we’d tell him, ‘This doesn’t make sense, blah blah.” We were just giving out input.

You have this line in the documentary where you say that, more than probably any other director, you’ve had these huge blow-ups in your career where you have to start from scratch. Why do you think this happens to you?

I think it’s the case with every one of us. You’ve got to recover from the catastrophes. Believe me—they’re not going to all be hits. You have to start over again. And a lot of times, the movie you made is very good just not received well, and you have to keep going. Blow Out was a catastrophe when it opened. It goes all the way back to Citizen Kane. And what about the famous Christmas movie that finished Capra’s career? It’s a Wonderful Life. Catastrophe! Didn’t make any money, the company [RKO] folded. For me, Bonfire may have been the toughest. I also got married, had a child, and moved north. And Get to Know Your Rabbit, having a film on the shelf that they’re not releasing for a year and re-cutting it and god knows what they’re doing with it, which is torture.

There’s a story you tell in the documentary about Sean Penn getting into a fight with Michael J. Fox on the set of Casualties of War that I hadn’t heard before. And Michael J. Fox seems like the least punch-worthy person on the planet.

Sean shoved him to the ground. Just shoved him. Sean I guess felt [Michael] wasn’t giving what he should be giving, and there was such tension built up in him over the month that we were there. Michael was just livid. Michael is the sweetest guy in the world, and he was absolutely livid when he got shoved to the ground. And that’s the scene that’s in the movie.

You also had to throw Oliver Stone off the set of Scarface.

Well, Oliver wanted to be a director and you can only have one director on the set. He was talking to the actors, so he had to leave. You can’t have him talking to the actors!

Throughout your career, you’ve worked with two of the premier Scientologists of the world in John Travolta and Tom Cruise. I read that on your pal Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, Cruise had a fully-staffed tent set up during production where they’d lecture people about the benefits of Scientology. Did you witness any of that on Mission: Impossible?

No. Definitely not. My experience with Scientologists is that they’re very honest. There’s no duplicitousness in a Scientologist—they pride themselves on being direct and honest—and that, for me, makes them very easy to deal with.

Scarface, too, is a film that has only grown more and more popular with age. And in the documentary, you say that Universal asked you to give the movie a hip-hop soundtrack but you turned it down. It’s pretty ironic as it’s since become very popular within the hip-hop community.

Nobody could have predicted how popular it would become. And that’s correct—they wanted to put a hip-hop score on the movie. They could probably sell a lot of DVDs. They come back to me every 10 years and ask me to put a hip-hop score on it, but that’s the advantage of having final cut. It’s like when they wanted to colorize Citizen Kane. They can’t do it because Orson has final cut. Believe me, if they could do it they would have. But with Scarface, it’s the immigrant’s rise to power, and many people in the hip-hop community identify with that.

What are your thoughts on the state of cinema nowadays? It’s become such an international business and there’s so much many at stake that everything is a tentpole. Studios see these high returns on these superhero and franchise properties, and it seems we’re nearing a bubble.

That’s why I watch the Turner channel a lot. Obviously at my age, there wasn’t going to be any way I was going to be interested in comic book heroes or seeing endless sequels, although I thought that the last Star Wars was quite good. They basically just remade the first Star Wars. [J.J.] is a very skilled director. It was fine. But you think of the time and money devoted to that, and you think, “Why?!” It’s repackaging old ideas.

I read your next film is called Lights Out. What’s that about?

I’m working on this thing with a blind Chinese girl that’s sort of a combination of Mission: Impossible and Wait Until Dark. She’s in her twenties, and like Wait Until Dark, all these people are coming after her because there’s something that they want in her house.

Wow.

Wow indeed.