Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge is Peter Orner’s second story collection, closely following the reissue of Esther Stories, Orner’s first, originally published in 2001. Like Esther Stories, this new book is divided into a four parts. These 51 new stories, from magazines like The Paris Review, Narrative, A Public Space, McSweeney’s, Zyzzyva, and Third Coast seldom span more than five or six pages, with a few mutations that metamorphose to more than ten. Orner objects, in general, to calling a short story anything else but a short story. I don’t. So—most of these stories are vignettes: short shorts, sketches, lightning flashes of fiction that last only a paragraph or two. Like poems entitled by their first few words, eight of the shorter pieces read like bookish diary or journal entries: they’re entirely italicized and stamped with a place and a date, maybe Orner’s crack at prose poetry. Anyway, Orner first published some of them as “Five Shards,” in the online magazine Guernica.

But no matter what their length, Orner finds idiosyncratic stories and tales to tell, and fascinating people and places to sketch: from Boston to Buffalo, Wyoming; from Chicago to Lincoln, Nebraska; from Minneapolis to Gastonia, North Carolina, from Moscow to Joslin, Illinois, in times that range from after Lincoln’s assassination to the digital age of the early 21st century.

Characters, or their relatives, from Orner’s previous stories drop by; other stories portray the personal reminiscences of new characters. Orner is a devotee of the short story and writes the column “The Lonely Voice,” named after Frank O’Connor’s book, over at The Rumpus. In this book, Orner pays literary props and shout-outs to writers he admires and shares writerly bonds with like Isaac Babel, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and John Cheever; although Eudora Welty, whom Orner considers America’s greatest, most bad ass short story writer, can’t fight her way into these stories. (See) The stories here are plenty bad ass.

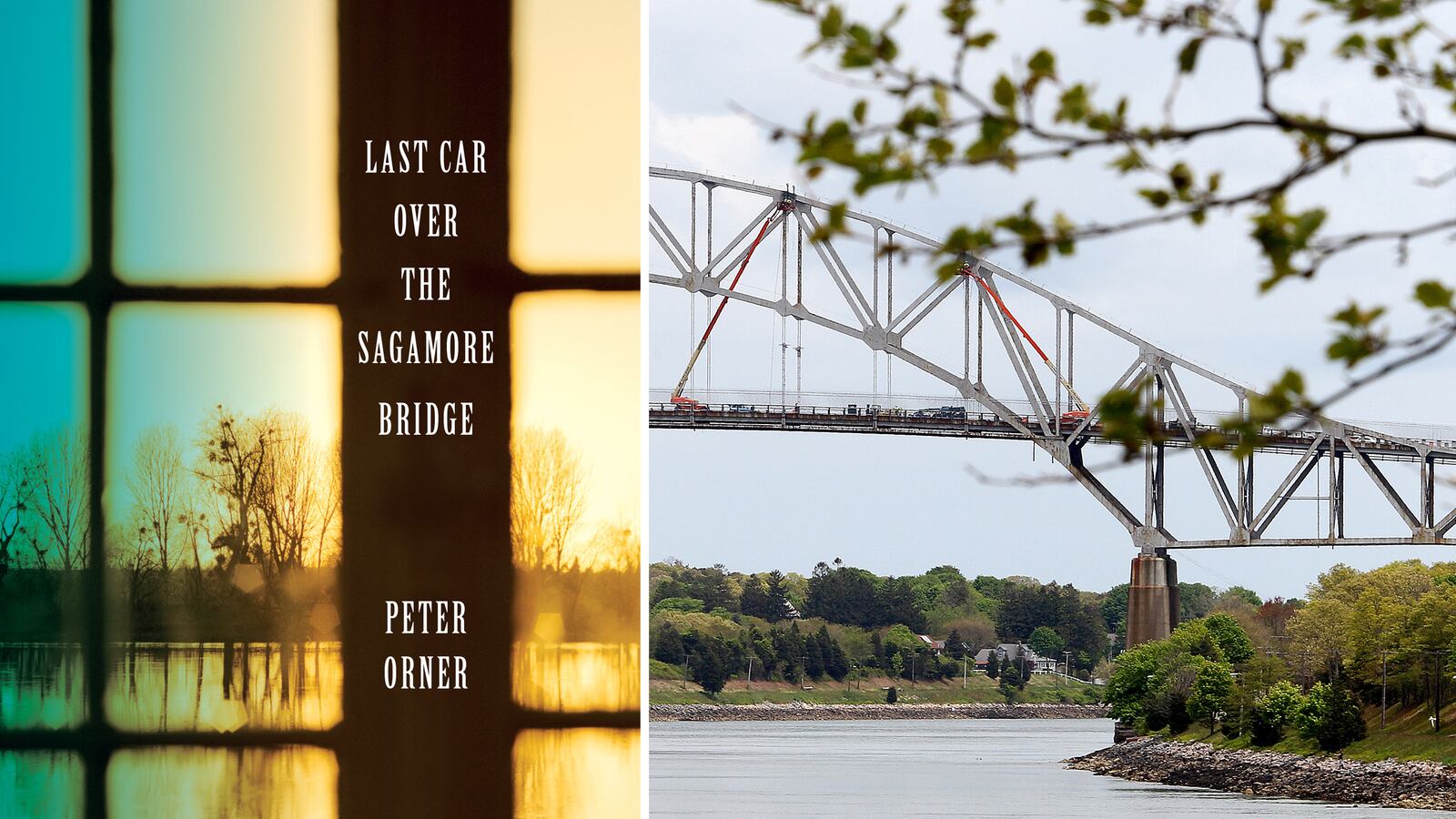

In the title story, Walt and Sarah Kaplan, characters from “Fall River Marriage,” Part 3 of Esther Stories, show up. Walt, “furniture salesman, daydreamer, reader,” sits in his shoe-box study thinking, “remembering lots of things,” he tells Miriam his daughter, in his head. He talks to Sarah, his wife, without talking: “He talks to the idea of her.” Neither wife nor daughter seems to be listening or even present. Conversing with his daughter Miriam (Walt does both sides of the conversation), he repeats for the 503rd time his story of saving her in his “Chrysler Imperial steed” when she was two years old from the New England Hurricane of 1938 “that sent half the cape into the Atlantic.” Saved! thanks to Walt, “hero of the Sagamore Bridge.”

Walt’s brother Arthur, unmentioned in Orner’s earlier Fall River stories, appears here as an accomplished academic in “Shhhhhh, Arthur’s Studying.” Walt went to work at father’s furniture store, but Arthur went to Brown and then to Columbia for his PhD in classics. He “came out of the womb speaking Latin.” When Arthur writes one seemingly innocuous history book, scandal spreads through Fall River.

In one of the longer stories, Herb Swanson tells a tall tale about being in Boston’s Cocoanut Grove in 1942 when the nightclub caught fire, one of the deadliest building fires in history. Later, Herb decides that the story about how he made up that story is just as good. In “Lincoln,” the narrator reminiscences about his and Samantha’s time together in Lincoln, Nebraska, and compares his loss to Mr. Ramsey’s loss in the “Time Passes” sections of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse,” where he “reaches out for Mrs. Ramsey in the dark of the morning corridor, not knowing she is already gone.”

A couple of pieces are historical vignettes. In Buffalo, Wyoming, during the 1912 state Republican convention, a married man has a brief affair with a maid at the Occidental Hotel. In Chicago’s Grand Pacific Hotel, Mrs. Lincoln suffers uncontrollable grief after the president’s assassination and faces, unbeknownst to her, commitment to an insanity asylum. We watch Babel beaten, just before his death, in “Lubyanka Prison, Moscow, 1940.”

A Fall River, Massachusetts, memory, one of the “Shards” called A couple years before I was born, recounts a time when the narrator’s older brother and mother ran away from Chicago and home to her parents, Grandpa Walt. Maybe the most imaginative of the “Shards” is told from the point of view of child remembering back before he was born. In I was six, maybe seven months old, the narrator remembers when his West Indian governess wrapped him in a towel and put him in the oven, comfortable as a new womb. A Highland Park sketch and prose poem called It may have been in The Wapshot Chronicle reminisces about the narrator’s mother and draws a comparison between her and those “heroically screwed up” characters in George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Whether you agree that short stories ought to be classified or you insist, like Orner, that a story is a story no matter how long, you’ll find all these realistic fictions intriguing, humorous, and sometimes poetic in a Turgenev-prose poetic sort of way. All sharp as the sword of a Babel Cossack. Though Orner organizes them by theme and they’re often linked by character, read them in any order you want—there’s something of the bad ass DNA of Babel, Cheever, and Welty here for everyone.