As the world watched an insurrectionist mob storm the U.S. Capitol earlier this month, eagle-eyed observers noticed that a handful of frontline rioters wore near-identical lower-face masks depicting skeletal jaws contorted into what writer Talia Lavin calls a “vicious Cheshire grin.”

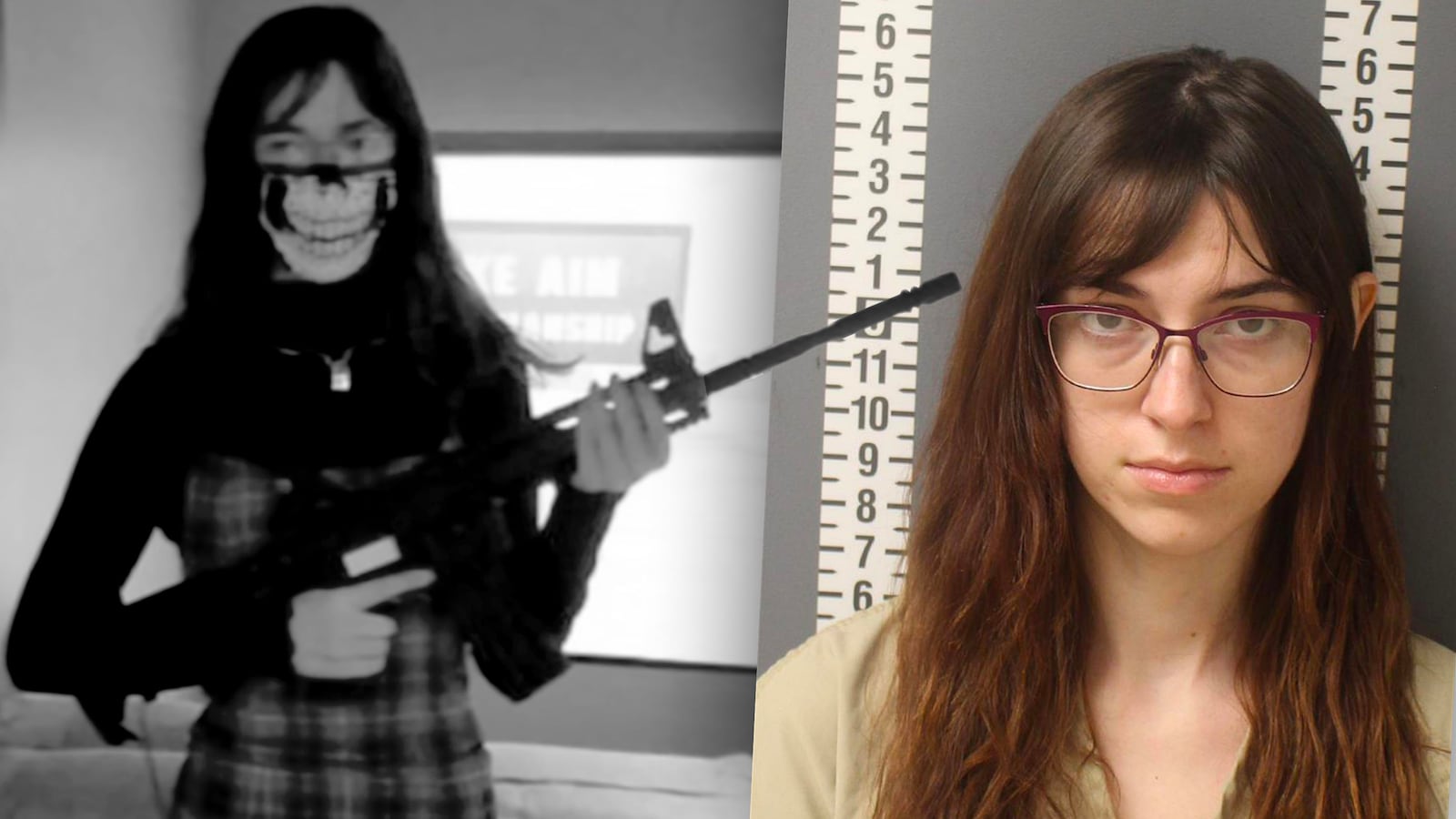

In the days since that attempted coup, images have surfaced of more Capitol rioters, like alleged Nancy Pelosi laptop thief Riley Williams, wearing the same skull mask in other contexts. (Williams’ attorney, Lori Ulrich, told The Daily Beast that neither she nor her client would comment on this story.) These skeletal grins have also popped up at subsequent pro-Trump state house protests nationwide, and in the avatars of numerous openly far-right individuals on social media platforms like Twitter.

Law enforcement officials, extremism experts, and even some mask wearers say these face coverings amount to “an aesthetic marker for those in the far-right culture,” as Cassie Miller, a research analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center, put it in a conversation with The Daily Beast.

However, recent coverage of masked protesters and rioters has not explained exactly what this skull means in the far-right world, where it came from originally, and why it seems to be growing increasingly popular. The spread of the Punisher skull, the Marvel anti-hero’s symbol, in far-right circles has been noted in recent years. But the skull masks seen at the Capitol use a clearly distinct design, and are embraced by different groups.

The Daily Beast recently spoke to about a dozen experts on the far right and combed through extremist materials to unpack the history and importance of this skull mask. What emerged was the story of a symbol that violent white nationalists use to wink and nod at each other—without courting widespread backlash or alienating potential converts.

Extremist watchers all agree this particular skull mask first gained traction in far-right circles in 2016, when members of Atomwaffen Division (AWD), a neo-Nazi group, started wearing it at public protests and in their carefully produced digital propaganda materials. Founded in the United States in 2015, AWD preaches accelerationism, the idea that America has been inexorably corrupted. Their deluded thinking maintains that the only way to save the white race from what they see as the slow genocide of multiculturalism is to stoke existing social tensions and commit isolated acts of terroristic violence. That, in turn, is meant to accelerate the supposedly inevitable death of the U.S. and birth of a new fascist ethno-state.

AWD members were active on IronMarch, a major accelerationist neo-Nazi forum that operated from 2011 to 2017. The forum incorporated the AWD skull mask into its own overarching iconography, declaring it “the face of 21st century fascism,” explaining that it symbolized a “rejection of individualism and egoism” in favor of fascist unity, and a commitment to “follow the Truth.”

Through IronMarch, the mask spread to other major accelerationist neo-Nazi groups worldwide, like Britain’s National Action or Australia’s Antipodean Resistance, according to Joshua Fisher-Birch, a researcher affiliated with the Countering Extremism Project. It became a powerful signal of their shared beliefs to insiders, as well as a tool for protecting their anonymity and projecting a sense of their intimidation. In far-right circles, “the mask is sometimes known as a Siege mask, after the book Siege by James Mason,” the father of modern accelerationism, Fisher-Birch added.

This deep and explicit neo-Nazi history explains why the reviews for grinning skull masks on even mainstream retail platforms like Amazon often contain coded white supremacist messages. One example: “would feel alright even when it’s 15 degrees F out or even 88 degrees F,” one customer wrote, a clear nod to 14/88, shorthand for the 14-word slogan neo-Nazis ascribe to, and for the 8th letter of the alphabet, H, two times in a row, which stands for “Heil Hitler.”

But why AWD adopted this skull mask in the first place remains somewhat opaque. Experts all stressed that numerous subcultures, like bikers and soccer hooligans, used similar skull masks as in-group symbols long before Nazis got their hands on them. So it’s possible that neo-Nazis lurking within these subcultures made a conscious choice to port the image into their white-supremacist activism, in part to appeal to others in those circles, Fisher-Birch argued.

However, experts disagree on which subculture AWD most likely drew from.

Christian Picciolini, a self-described de-radicalized neo-Nazi, argued that “the mask came from Call of Duty,” the popular first-person-shooter video game series, which released an installment called Ghosts featuring ace soldiers wearing skull masks in 2013. “As many people in Atomwaffen Division were gamers, and recruited [new members] while playing games, it became a symbol for them,” he told The Daily Beast. (Activision Blizzard, the company behind the game, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Joan Donovan, a Harvard media and politics researcher who studies extremist symbols and memes, argued that AWD propaganda “looked like old punk flyers that used skulls and high contrast imagery.” She added that there’s always been a far-right, neo-Nazi element within—and eager to utilize the imagery and tools of—punk, heavy metal, and other musical subcultures.

It’s also entirely possible that, because skull masks are common, someone involved with AWD just saw one by chance in a store, thought it looked cool, and told their friends to buy it for their videos, argued Mark Pitcavage, an extremist group and symbol researcher with the Anti-Defamation League. Indeed, Peter Smith a researcher at the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, recalled in a conversation with The Daily Beast that a de-radicalized neo-Nazi recently told him he and his compatriots started wearing the masks as a random lark.

No matter where they found them, Holly Huffnagle, an anti-Semitism researcher at the American Jewish Committee, explained, these skull masks likely resonated with neo-Nazis because they harken back to the Totenkopf. That’s the smiling skull angled to one side and set over nubby crossbones which Nazi SS officers wore on their uniforms. But they achieve that resonance without directly referencing or copying that known hate symbol.

“It has a sense of ambiguity,” explained Miller of the mask’s backdoor ideology appeal. “It’s not a swastika. It does not have overt racism, obvious to the general public, attached to it.”

It also conveys a sense of menace to outsiders while appealing to “nihilistic young wannabes looking to do harm,” as Jason Blazakis, an extremism researcher at the Soufan Group, an intelligence and security think tank, put it.

“When you have a bunch of guys lined up in those masks, it’s like an intimidating wall of death,” added Smith.

However, the AWD has been falling apart over the last two years in the face of a wave of arrests and crackdowns on their media channels. And although some accelerationists from other groups still don skull masks on occasion, the movement as a whole has started to move away from them in recent months, Smith noted.

“Modern guides on making accelerationist propaganda say to wear black balaclavas instead, as everything should be uniform and nondescript,” he explained. “Skull masks look the same from a distance, but when you really break down the images, you can tell if one is a Call of Duty mask or another is from Wish.com. So it can be a distinguishing mark.”

That differentiation puts extremists at risk of doxxing or arrest and goes against their ostensible belief in the importance of erasing their own identities and presenting themselves as one large, anonymous, threatening group entity.

But just as skull masks started to lose currency in the accelerationist world, they gained traction in wider circles—and not just among non-accelerationist neo-Nazis. “Individuals with a broad array of political views have been wearing the mask recently,” Fisher-Birch pointed out.

“The first time I remember seeing the masks outside of the accelerationist neo-Nazi milieu was in the summer of 2019, during far-right protests against drag queen story hours,” recalled Miller. Those maskers appeared to be Proud Boys, which surprised Miller, because although members of the group often express deeply white-nationalist sentiments, she and many other researchers do not believe that the movement as a whole is explicitly organized around neo-Nazi ideas and tropes.

A Proud Boys Parler account also created some notable skull mask memes during the Capitol insurrection, like one photoshopping the symbol over Tucker Carlson’s mouth, and making his eyes glow red, above a blurred Fox News chiron reading, “Is force now more effective than voting?”

Some Boogaloos, the infamous, meme-drenched, quasi-ironic nihilists who oscillate chaotically between apparent support for Black Lives Matter and white supremacist rhetoric, also started to wear AWD-style skull masks in 2020.

Even a few (possibly very confused or ill-informed) antifa protesters have been photographed in recent years wearing AWD-adjacent skull masks, despite their opposition to everything that group and its ilk stand for.

“As I’ve watched this skull mask seep into the far right, what I see it showing is that a larger part of the far right has been adopting accelerationist beliefs,” Miller argued. A Boogaloo Boi in a skull mask who garnered some media attention in early 2020 actually called himself Big Siege.

There are always points of overlap or communication between conspiracy and hate groups, no matter how divergent elements of their idiosyncratic philosophies or tactics may seem. And in the aftermath of the 2020 election especially, hardcore accelerationists have actively been trying to recruit and radicalize disaffected Trump supporters, introducing them to back catalogues of hateful memes and videos chock full of skull masks.

However, Pitcavage cautions that you can’t always draw a direct line between AWD propaganda and skull masks popping up sporadically within the big, ugly tent of the far right. The masks have become so visible in the media in general over the past year or two that other groups may just think of them as broadly intimidating symbols that will get a rise out of people when they protest, and draw them media attention that they deeply crave. Skull masks have also gained traction through ostensibly ironic memes on sites like iFunny, added Huffnagle, so some wearers may just think of them as provocative trolling symbols. (Meme irony is often just a shield for presenting hate and bile.) One group of protesters at a pro-gun rally in 2020 actually explicitly claimed that they were from a shit-poster Facebook group, and were wearing skull masks to reclaim the symbol from the far right. For what, they did not say.

This ambiguity makes it hard to say what anyone in a skull mask actually believes, especially at a sprawling, deplorable event like the Capitol insurrection. And that is the real threat of the masks, Huffnagle argues.

“They blend in. But for those who know what to look for, they are clear dog whistles.”