Three men sit inside the entrance of the Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn on a recent Saturday in September, having a conversation about the infamous hip-hop magazine The Source.

“They ended up going bankrupt because of what’s his name…” one of them says.

“Benzino?”

“Yeah, Benzino. Then that feud with Eminem...”

The show they’ve come to see is the crown jewel of The Source’s first ever SOURCE360 Expo, a three-day festival consisting of panels, contests, movie screenings, and music. Streaming past the trio is a diverse crowd—blacks, whites, Latinos, Asians, all here to soak in the sounds of ‘90s and early ‘00s rap. They arrive in orange sweatshirts and camouflage pants, baggy jeans and black windbreakers, white tees and flannel shirts, short skirts and flat-brimmed hats. The lineup features such hip-hop luminaries as Lil’ Kim, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, Dipset, and the Wu-Tang Clan.

But what is supposed to be a celebration of the genre soon feels like the last gasp of a golden era gone by. Each act steps into a half-filled arena ripe with blunt smoke, performs for 30 minutes, then abruptly drops off the stage to half-hearted, half-confused cheers. Lil’ Kim signs off her set by saying “I am out here on some favor shit,” a comment that makes it sound like she has come here not by choice, but by obligation. By the end of the evening, concertgoers—weary from the audio issues during several performances and the extended time it takes for acts to get on stage—are only slightly more enthused to throw up their Ws. It’s not the energy level you’d expect from a hometown crowd.

The entire weekend was billed as a celebration of “the cultural community inspired by the legacy of Hip Hop [sic].” What you didn’t see on the advertisements: this expo was as much about community as it was about putting The Source back in the cultural conversation after years of distrust and incongruity.

The Source launched 26 years ago at a time when hip-hop was still coming into its own. Back then, the idea of rap journalism was a pipe dream. The genre itself was reserved for a niche audience—at least comparable to the one it would spawn years later, when the music began infiltrating mainstream radio and other corporate entities. The Source was initially created to help serve that niche, covering the industry with commentary, reviews, and reported features.

The brand soon came to epitomize both the best and worst parts of the culture. While it became one of the bestselling titles in the country, it also fell prey to the same needless feuds that occurred between the rappers they were writing about.

Now The Source finds itself in the unenviable position of having to reinvent itself again, this time in a volatile publishing world where one of its main competitors, VIBE, has shut down its print edition, and rival rap mag XXL has been sold to another media conglomerate. The Source is looking to recapture the buzz they once had, when rappers were still gunning for the Hip-Hop Quotable or Unsigned Hype columns, when the magazine would get shout-outs in songs, when The Source was the source for all things hip-hop. But can a rap industry giant return to glory if no one is listening?

***

“We’re still here, we never stopped printing, even through all the bullshit and drama,” says a boastful L. Londell McMillan, the publisher of The Source, three days before the start of the expo. McMillan sits at a short table inside the magazine’s current third-floor office, a long, narrow space located in midtown Manhattan, where large posters of previous Source issues line the wall. The office is split into several sections. On one end, employees sit at a table banging away at computers. On the other, there’s a conference room. Connecting the two is a compact reception area and hallway. Like any once-successful magazine, The Source is no longer swimming in money. Gone are the days of corner suites, an on-staff barber, and diamond medallions given to employees. Now, it’s all about producing a magazine that doesn’t break the budget.

“We’re a tight, lean, mean machine,” says McMillan. “I outsource and use a lot of independent writers. I try to continue to produce a quality product, try to give the artists what they want, and get back to the basics of establishing relationships so people can get better stories.”

Getting back to being a top-tier magazine would be difficult for any publication in this environment, let alone one with such a complicated history. Shrinking ad revenue in the digital era has caused outlets to scale back on everything. For The Source, things are even more challenging, as it is in the awkward position of not having an editor-in-chief. The current barebones masthead only lists McMillan as publisher, Don Morris—who left in July—as “contributing creative direction,” Khari Nixon as music editor, 12 staff writers, and a copy editor. The last editor-in-chief, Kim Osorio, stepped down in April 2013, with no official announcement regarding her departure. Since then, the magazine has been run by committee, with more senior staff guiding the content, and McMillan representing the overall face of the brand.

“We don’t actually have anyone that runs it,” says McMillan, when asked about the current editorial process. “Different people have different departments. We do it by group. We don’t have a head honcho.”

While McMillan’s method might be a more democratized way to run an outlet (it’s certainly cheaper), whether it produces a better product or not is debatable. In fact, sometimes it doesn’t produce one at all, at least on the print side. As of this writing, The Source has published only three issues in 2014—low even for the magazine’s current bimonthly status—making the “never stopped printing” comment a bit of a misnomer. The extra time this year has been devoted to both online content—according to McMillan, the website, which is mostly made up of aggregated articles, reviews, and song premieres, averages over three million unique visitors a month—and the planning of the expo, which the publisher and owner hopes to turn into an annual event. The current print circulation, also provided by McMillan, stands somewhere between 175,000 and 250,000, depending on the issue. However, I was unable to verify that number independently.

To McMillan’s credit, he has been able to keep the magazine afloat after several ugly, high-profile incidences that occurred before he arrived. But he is also the first one to tell you that the product isn’t where it should be right now. Current and former staffers I spoke to had similar things to say.

“Real talk, the shit is really bad, but I want to hopefully paint a better picture of what it could be,” a Source staff writer tells me.

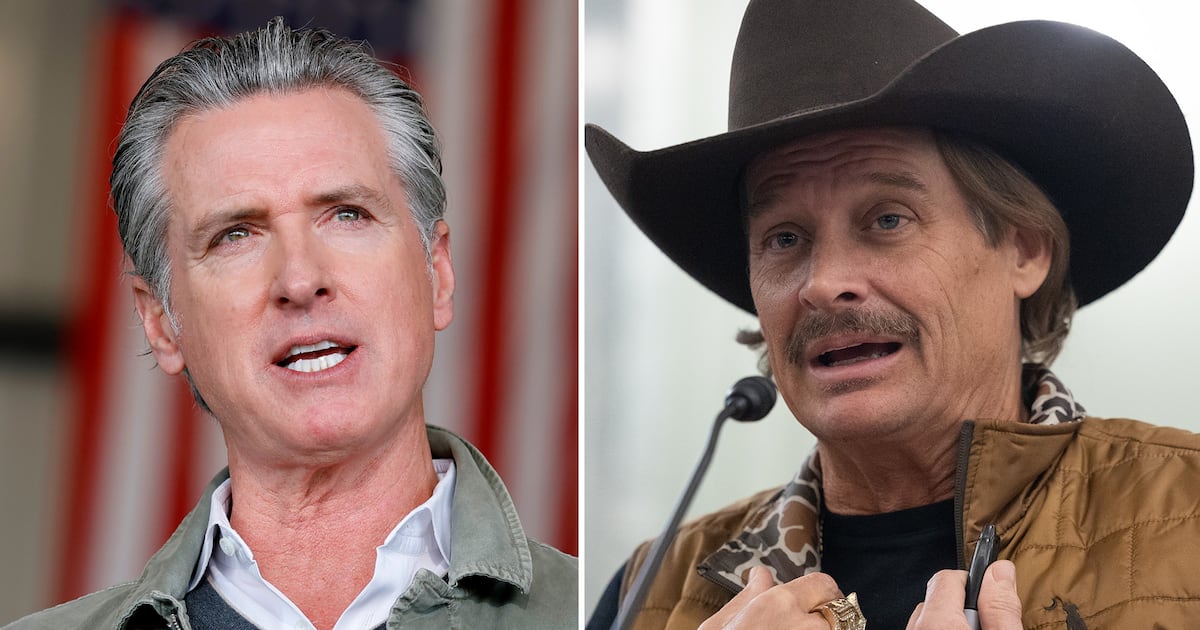

“If we did a list of top hip-hop magazines, I wouldn’t put The Source in it because I can’t do what my predecessors did, which is celebrate themselves,” says McMillan, referencing infamous Source founder Dave Mays and his confidant Raymond “Benzino” Scott, who were thrown out of the magazine in 2005. “I think we’re getting it right,” adds McMillan. “It’s just taking longer than it should. We made a lot of errors but we learned a lot. I like our chances to be honest with you.”

The Source wasn’t always the underdog. On the contrary, it used to be the be-all, end-all of hip-hop journalism. If you were a rap fan, this was your magazine. It didn’t matter if you were black, white, from the suburbs or the city, The Source spoke with authority on a genre of music a sizeable and dedicated group of fans cared about. It was written by hip-hop fans, for hip-hop fans. At its height, The Source had a reported circulation of 500,000 and was outselling Rolling Stone on the newsstand. Releasing a new issue was like dropping an atom bomb on the industry.

So how did a popular magazine that was considered a pioneer of the genre end up getting left in the dust? The dawn of online journalism certainly played a part, as did hip-hop’s evolution, when the genre transformed into something different from what The Source had initially championed. But if you were to blame one thing it would be the magazine’s ugly history—what McMillan referred to earlier as “bullshit and drama.”

***

The great irony of The Source is that this bastion of rap journalism and street life was launched in 1988 by two Jewish white guys named David Mays and Jonathan Shecter, from the cozy confines of Cabot House, an undergraduate residence at Harvard University.

“At one point, Dave and I each took $100 out of our pockets and put it into a fund for launching The Source,” Shecter, now an editor at Medium, tells me. “That was literally our budget in the very beginning. As it grew and as the project took on a broader scope, we began to realize what it could be.”

The first issue ended up being closer to an industry newsletter than an actual magazine. Mays and Shecter eventually brought on two black Harvard students, H. Edward Young, who handled the business side with Mays, and James Bernard, who took charge of editorial with Shecter. Young began traveling around the country, convincing wholesalers to stock the magazine. His goal: get it in the hands of suburban kids.

“I had meetings with these old white guys and explained to them, the new pop music was [hip-hop],” says Young. “And they were like, what are you talking about? Here was this young black guy from Harvard telling them that this magazine with angry black men’s faces on the cover was really appealing to the white kid audience. None of them believed me.”

They should have. As Jeff Chang writes in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, two years after The Source’s first issue, it had a readership of 15,000. The editorial staff named themselves The Mind Squad—a label that sticks to this day—as the magazine became a tastemaker for everything in and around hip-hop culture. It soon broadened its scope to include essays and reported features on a wide range of topics, from the Anita Hill scandal to the Los Angeles Riots to the portrayal of women in rap videos. It featured Puff Daddy and Tyson Beckford in their first photo shoots, and then-unknown artists DMX, Common, Mobb Deep, and Notorious B.I.G. in the Unsigned Hype column, which highlighted up-and-coming talent. One of the most popular sections was the infamous Record Report, which rated new albums on a scale of one-to-five mics, five being a certified hip-hop classic.

By 1991, The Source had become the industry bible, building a circulation of 40,000, with nearly $1 million in total revenue. At the same time, tension was rising within the company. Editors and writers were being threatened over negative reviews, and sponsors were thinking of pulling their ads. Then there was the relationship between Mays and Raymond “Benzino” Scott, an aspiring rapper Mays had befriended while he was at Harvard. Scott had a group called the Almighty RSO, and Mays became their manager, a job he continued during his tenure as publisher of The Source. Eventually, Scott began stopping by the offices and intimidating editors into covering his music. As Bernard told Chang in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: “My main problem was that there were a lot of people who were armed at The Source. My fear was that things could get really out of hand.”

Things came to a head at the end of 1994 when Mays inserted a last-minute, three-page feature on the RSO without telling anyone on the edit side. Editors were apoplectic, and they showed it by quitting en masse, leaving Mays to pick up the pieces.

By the late ‘90s, the magazine continued to grow in circulation and influence. But The Source was also starting to develop a bullying reputation within the industry. The rap feuds the magazine had been writing about began spilling outside the pages and into the office. They were soon blackballing anyone who wanted to write for a competitor, particularly XXL, the magazine Bernard created after leaving.

“When I started at XXL so many people that I was trying to work with were like, ‘We can’t work with you. The Source will never work with me again,’” says Don Morris, who was at XXL before becoming creative director at The Source, in 2006. “Same thing with Vibe. Everyone was told, ‘If you work with XXL, you’re not working with us.’ So I would have people who would work with me for a minute and then get a contract with Vibe and I would never see them again. It was just dumb.”

Andre Torres, the former editor of Scratch Magazine, which began as an imprint of XXL, remembers similar hostile situations.

“XXL really strengthened their position once [former Source staffer] Elliott [Wilson] got in there and became a thorn in their side,” says Torres. (Full disclosure: I briefly worked for Torres at his current magazine, Wax Poetics.) “It became a war. Right after we got to XXL, they had security out front because Benzino had showed up with some dudes at the office and they were trying to get in the back. I am like, This is a magazine! Are the guys from Vanity Fair and Time battling it out and trying to get gangster with each other? No. Like, y’all are stupid. This is how serious this shit was getting. Luckily nothing really happened, other than the fact that this brand lost all its credibility.”

Other alleged issues at The Source at the time include (but are not necessarily limited to): freelancers not getting paid, favorable album reviews being given to friends of the publisher, missing payroll for full-time staffers, using company funds to support Scott’s albums or photo shoots, and Scott (again) threatening writers with violence.

By 2003, Scott began feuding with Eminem, then the biggest and most powerful rapper in the game. The two would jaw back and forth in mixtapes and in the press, with Scott using his power as Source “co-owner” to write stories and cover lines that said things like “Benzino Sets the Record Straight and Sparks a Revolution.” One feature had an illustration of Scott holding Eminem’s decapitated head. (Years later, Scott would apologize for his role in the feud.) For readers who had become familiar with The Source’s earlier transgressions, this was the last straw. Circulation began to decline and Eminem’s label, Interscope, pulled all of its advertising from the magazine. (Things between the label and the magazine appear to be better now; the group Slaughterhouse, which is under the Interscope imprint Shady Records, was featured on the cover in 2012.)

At the same time, Kim Osorio, the magazine’s first female editor-in-chief, was running into issues of her own. As she details in her book Straight From The Source, Osorio began getting unwanted sexual advances from Scott. (Scott did not respond to repeated requests for comment.) She also claimed that male employees were being treated better and getting higher wages than their female counterparts. In 2005, she filed a lawsuit against The Source and its owners for sexual harassment, gender discrimination, retaliation, and defamation. She won on the latter two and was awarded a reported $8 million settlement.

By 2006, after more than a decade of mismanagement and bad press, Mays and Scott were finally forced out of the magazine, and the company was thrown into bankruptcy. The tipping point? The duo had defaulted on a loan from Textron Financial for $18 million.

With Scott and Mays gone, the magazine looked to the future. That’s when McMillan stepped in. He had already been involved with The Source, having been a creditor of the company. Four years later, after becoming publisher and owner, he hired back Osorio as editor-in-chief of The Source and vice president of content and editorial for NorthStar Group, the company that owns the magazine. It was a cathartic moment for the brand, though far from a guarantee to help restore it to its glory days.

***

“When I came back I wasn’t surprised at myself,” says Osorio. We’re driving through Manhattan as she discusses her tenure at The Source and why she inevitably returned to a place that had treated her with such disrespect. “I always felt like leaving on bad terms left this hole in me professionally. I had done so much and accomplished so much, I hated the fact that I split from the brand. Again, forgetting about the owners and everything they did, I was in love with The Source. I was in love with being there.”

Osorio got her start at the magazine in 2000 as an associate music editor. She quickly rose through the ranks and was soon given the reins by Mays and Scott. However, the working environment had grown contentious. As she states in Straight from the Source, Osorio allegedly witnessed employees being sexually harassed by the Boston-based rapper:

I’d seen Ray [Scott] pursue her heavily. The touching and groping was obvious. He would pull her toward him, hug her, kiss her, and stroke her hair. Then when he looked away, she would make a face as if she just drank a cup of sour milk. She always resisted. But like many women at their jobs, resisting doesn’t always mean you tell your boss to fuck off.

At some point, Scott would turn his advances toward Osorio. But complaining to human resources got her nowhere. Her personal life also began getting pulled into work discussions. The romantic relationships she had with Nas and 50 Cent while she was an editor of the magazine became water-cooler gossip, particularly for Scott. Not helping matters was Eminem calling her out directly in a Benzino diss song: “We are not killers, my vato will have you shot, though/Dragged through the barrio and fucked like Kim Osorio’s/Little sorry ho ass, go ask B-Real/We burn Source covers like fucking Cypress Hill,” he raps in “We All Die One Day.”

Osorio was eventually fired in 2005, after sending an email to HR regarding Scott's inappropriate behavior. When Scott and Mays pressured her to retract the allegations, she didn’t, so they got rid of her. Then she filed the lawsuit. After The Source, Osorio became an executive editor at BET.com before McMillan came calling. She was able to bring the experience she learned at BET to help with the magazine’s digital arm. But The Source she returned to had been decimated by the recession, the Internet, and Scott and Mays’s handiwork.

“When I got there the resources were so limited,” she says, candidly. Still, it was without the two people who had made her job a living hell. “The brand is not evil," she adds. "It’s been in the hands of evil people before, but when you’re detached from it like that, it’s like, Oh I still care.”

Later, she talks about The Source’s attempts at digital integration. “I think they’ve done a good job in trying to catch up, but they are so behind. And I think that really comes back to the voices you have and the people you have working there. You’ve got to find that crowd, even if it’s in today’s generation. And you need leaders as well. But hip-hop spans so many different generations now.”

The most recent issues attempt to help bridge that age gap. Wiz Khalifa and Young Jeezy were on the cover; April's issue had Schoolboy Q and Ice Cube. But the actual writing is lacking the same bite from the publication’s glory days. The current issue is also filled with dozens of grammatical errors and spelling mistakes. And while the story selection itself isn’t bad—features on credit card scams and international coverage of the protests in Ferguson are both in the spirit of what The Source used to be; a section called Her Source, devoted to females in hip-hop, also deserves extended praise—the magazine lacks the overall resources it needs to help build it back up.

“The Source has a lot of work to do,” says Osorio. While she still contributes to the magazine, having written a cover story for the December 2013/January 2014 issue on Macklemore, she now sees herself as more of a motherly figure to the brand. “I still care. If I see something that I don’t think is appropriate, I will talk to Londell and say, ‘Oh you guys can’t do that.’”

That instinct pops up when we start discussing the magazine’s current output.

“I think we did some really good things. And I still see glimpses sometimes—like, oh The Source did that? That’s cool. You don’t see it as much. I don’t know how many issues have come out this year…”

At the time of our interview, only two had come out.

“Who was on the cover?” she asks, about the most recent issue.

“Ice Cube and Schoolboy Q.”

Osorio seems dumfounded by the decision.

“What? That doesn’t even make sense. See, that’s the problem. There’s no editorial vision in terms of…” she trails off. “I haven’t said I am not at the magazine but I hope people don’t think certain things represent me. Not because I don’t see the effort but it’s not what I would have wanted.”

I say I figured she wasn’t there just because her name is no longer on the masthead.

Osorio’s response: “Good!”

***

In 2006, Nas proclaimed that hip-hop was dead. Most people saw it as a way to boost album sales, which it kind of was. But it also helped promote an open discussion about the genre and whether it was actually still around.

So what is hip-hop in 2014? Is it Drake? Is it Kanye? Is it Jay Z? They are all certainly part of hip-hop culture, but are they actually making hip-hop music? That depends on your definition. Some older heads say Drake’s crooning disqualifies him, that Yeezus is more of an art project than a rap record, that Jay Z is too commercial and corporate to be “real hip-hop.” And that’s one of the major problems facing The Source right now. How do you court younger readers and keep your older audience when they may be into two different genres? More importantly: How do you stay true to the message and cover what’s hot in the industry when what’s hot may no longer be the thing you and your once-loyal fan base held sacred?

“I think Hip-Hop Weekly speaks more to this generation than The Source does,” says Torres, the former editor of Scratch, referencing the tabloid Mays and Scott founded after getting the boot. “And I think that has a lot to do with hip-hop’s evolution and what hip-hop means to a group of people like myself, who are in their 40s, and what hip-hop means to kids who are in their 20s. I have been talking with a lot of younger kids now and I am convinced that they aren’t even making hip-hop anymore, and so are they.”

Still, not everyone is as quick to write off The Source, particularly those who currently work there.

“The Source knows new talent when they see it,” says staff writer Brandon Robinson. “Twenty-five years and to still have longevity? I think that’s rare these days, particularly for magazines in general.”

“As long as we make this transition into the digital space, I don’t see The Source going anywhere,” says Bryan Hahn, another Source writer. “Because you will still have the older guys telling the younger guys, ‘You need to get in The Source, you need to be in Unsigned Hyped.’”

“I am actually encouraged by recent activities,” adds Shecter. “I think that Londell is a good guy. I like him a lot. I’ve met him and I think his head is in the right place. I’m glad that he is at the helm of it.”

As for those who doubt the brand’s durability, McMillan has a special message for them:

“I would just say 300 percent growth on digital over the past nine months, I’d say a multi-venue multi-sponsored arts culture and music festival in Brooklyn, I’d say major artists back on the cover and shouting us out in records, I am saying just get your head out the sand and just see what’s really going on.”

Times change, magazines come and go, that genre of music you once held sacred morphs into something else entirely. The recent sale of XXL, a magazine launched in the wake of The Source’s popularity, is an exclamation point on how unpredictable things have become for the godfathers of hip-hop journalism. After the sale, a report stated that XXL, like VIBE, would be stopping its print edition, but that turned out to be false. The initial rumor prompted McMillan to make a slight boast about his competitor’s move to digital-only content. “OK...We outlasted XXL in print with @THESOURCE, we are heavy in digital also, & just made history/herstory in BKLYN w/ #SOURCE360 #NorthStar,” he tweeted.

Yet without money, without access, and without readership, that history McMillan seems intent on making will be absent. All you’ll have left is a dying star of a magazine, devastated by recklessness and a transforming media and music landscape. At the very least, The Source needs to be on people’s minds again, even if the conversation skews negative. Take what Morris, the magazine’s former creative director, told me during our interview: “When I first got there, people were like ‘Fuck The Source.’”

When’s the last time you heard anyone say that?

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article stated that XXL would be closing its print edition, based on initial reports following the magazine's sale to Townsquare Media. That turned out to be untrue. XXL will in fact be continuing its print edition.