Daniel Torday’s The Last Flight of Poxl West is a debut novel about honoring the past, even if it means exposing its mistruths. It’s about loving your family, even when your family isn’t family, and even when war stories turn out to be inflated. It’s also about love and lust, about the darkness in all of us, and about how admiring our heroes too much is bound to leave us disappointed in the end. Winner of the 2012 National Jewish Book Award for his novella The Sensualist, Daniel Torday spoke to us about his remarkable novel, so full of generosity, even as he gives a pass to Brian Williams.

You have written a provocative novel about the relationship between a teenager in Boston in the ’80s, whose Jewish Czech uncle—who is not really his uncle—has published a memoir of having been forced to leave his home north of Prague before World War II, and ends up flying RAF bombers, killing thousands of German civilians. How did you manage to cover that territory in an entire novel without using the word “Holocaust”? Was this your intention from the beginning, and if so, why?

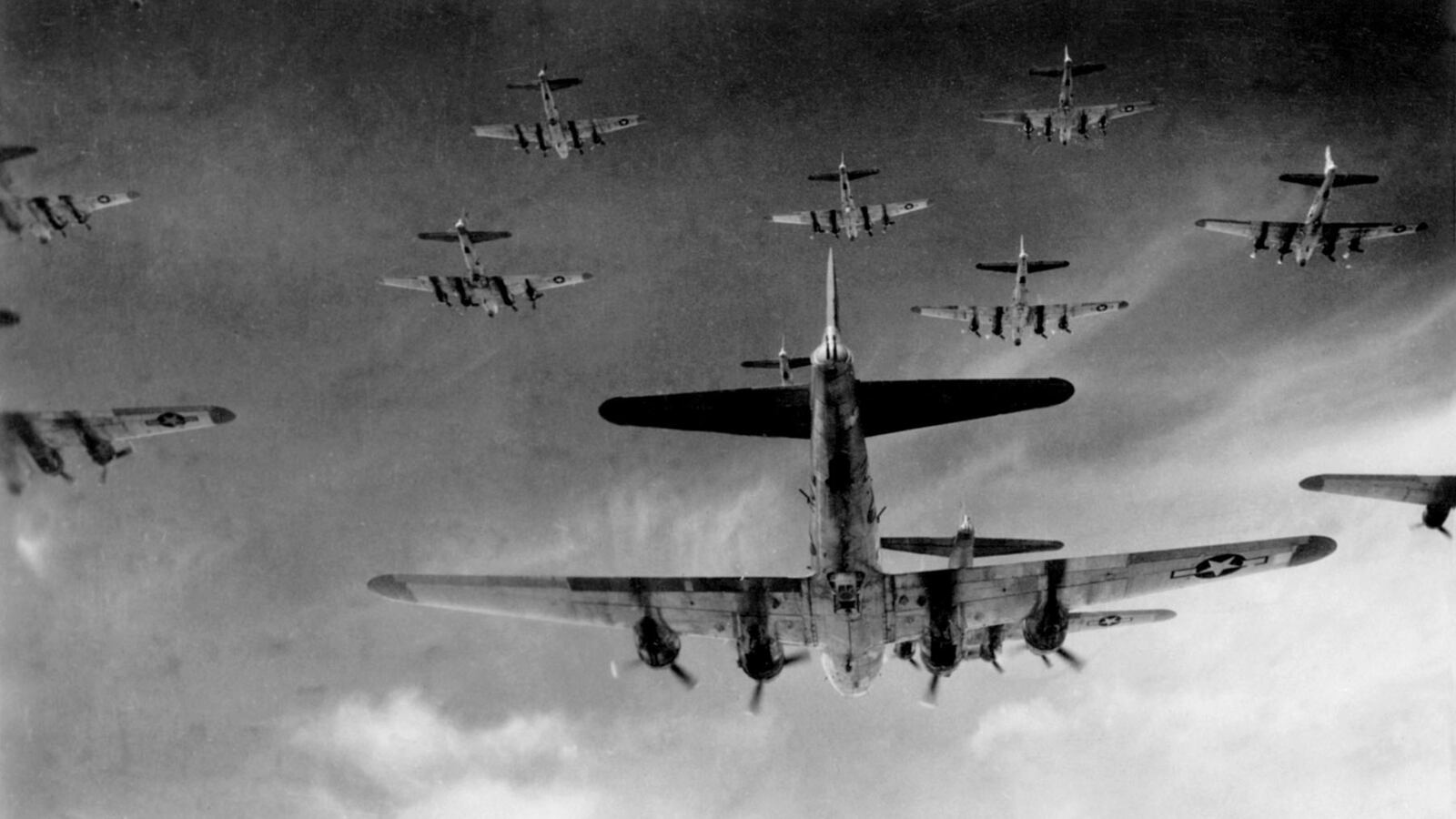

Ah, starting with the third rail question! I like it. Well, let me preface this question by saying first: Almost every member of my father’s Hungarian and Czechoslovakian family was killed in death camps during the war. So I hope all my answers here are taken with that caveat—that I was raised in the shadow of that awful history, and I’m deeply sensitive to it. Formed by it, even. But in writing this book, I was hoping to really look at those war years afresh when I took up this character of Poxl West. All of what I read in the buildup to writing this book, about the Allied bombing of Germany in the last years of the war, was news to me. My grandmother had a first cousin who had trained for the RAF, and when I started talking to him, and then reading up on it, there was just this whole other version of the war I’d never heard. Those conversations coincided for me with reading W.G. Sebald’s On the Natural History of Destruction, which was translated and published right around the time I started writing—Sebald provides a history that, to my understanding, hadn’t really been discussed, in Germany or elsewhere, about the more than one hundred cities that were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of German civilians who were killed, by Allied bombing.

Which is all to say: I want to be very sensitive in the way I say this, because I think there were very good reasons for the way the language and the thinking that accompanies it about the war have developed since the ’60s. But in some way, just putting that capital-H word on a conversation could come to shut it down, to flatten it—and perhaps to keep us from thinking about the complicated particularities of a long, complicated war. I just wanted to take that on, to look at the life of this single character during a war that lasted half a decade. Or let me keep this more personal, I guess: in some way, applying one big proper noun might have kept me at times, especially when I was a kid, from understanding my family's history during that period. I wanted this book to be similarly open to the specificity of that period.

Your novella, The Sensualist, won the Jewish Book Award, and your work is steeped in Jewish themes in the tradition of Bellow and Roth. Yet your own Jewish background is complicated. What is the story behind that and how did that affect your predilection for literary Jewishness?

Well, this is a central question, isn’t it? But also complicated. I’ll try to be as succinct as I can: My father emigrated from Hungary with his parents in the early ’50s. My grandmothe’s family, out of fear of what was to come, had actually converted to Catholicism in the late ’30s. My grandfather had false papers created for himself during the war. Hungary’s Jews, as I understand it, were really the most assimilated in Eastern Europe since the turn of the century, so this was all not entirely uncommon. Which added up to my father growing up not quite knowing he was Jewish—even when I was a kid my grandparents went to Midnight Mass on Christmas. My grandmother died never admitting she was Jewish in the 40 years she lived in New York. And my grandfather never quite learned to be fluent in English.

But my father did have an aunt who lived on the Upper West Side, who had left Hungary before the war. And on weekends in the city, she told him about his background. So it was always this kind of ambient cultural identity for him. Then he married my mother, who had her own complicated but perhaps more common religious background—she grew up in Boston, her father was very devout, they went to a shul where the women sat up in the rafters and the idea of a “Bat Mitzvah” would have seemed impossible, so she had no Hebrew education, either. My father was Bar Mitzvahed the year before I was—he was a successful research scientist running a lab at Harvard, and at night he studied Torah. My grandparents came down from Long Island for my Bar Mitzvah, but not his. I made it all the way through confirmation when I was a teenager, and then didn’t discover Bellow Roth Malamud Singer until late in my reading life. Which is all to say: We’re Jewish! I am. But it’s very complicated.

And so is this book, more than the young Eli can grasp at first. The first thing Poxl says is, “Then today ... the deus ex machina,” and even though teenage Eli doesn't know what this means, the narrator does. How would you describe the deus ex machina of this book?

I’m going to take you very literally on this one. If there’s a god running the machine of Poxl, I think it’s one that seeks to value truth over fact. There’s a moment at the end of one of my favorite books, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, where the narrator, Ruth, just steps back and says: “All of this is fact. Fact explains nothing. On the contrary, it is fact itself that requires explanation.” And I guess I’d say if there was an impulse behind all of what’s in this novel, it was a fear that we’ve come to invert that equation of late. I mean, I think we’ve come by it in earnest—I remember all the fear we felt just after 9/11, and all I wanted was facts. I remember sitting up in my Brooklyn apartment all night for weeks watching the CNN crawl—that was still years before people had wireless at home, nearly a decade before the first iPhone. The Internet came along and just brought us all this information, and we’re hard-pressed to sort it out. And we went through so many iterations of it—is it a fact that Saddam has weapons of mass destruction? Is it a fact that you go to war with the army you have, not the one you want? And part of me wonders which facts we're nosed up against right now, missing the truth—is it a fact that fracking has cut oil prices in half? It is. But what truth does the fact of the corresponding flammable water in those rivers tell?

There’s this thing that Henry James said I’ve always loved, something like, “No superficial mind will ever create a first-rate novel.” I remember reading that and thinking, Oh, god, is my mind superficial? And the best I could come up with as a salve was to try to take that one literally, too: not the surfaces of things, not the facts on their faces. The stuff underneath, the truth running in the aquifers underneath. I can’t say if I got to it in this novel, but I know I aimed for it in earnest.

Henry James also said, “Be one of those on whom nothing is lost” and also, “Three things in human life are important: The first is to be kind; the second is to be kind; and the third is to be kind,” and I see both of these impulses in this book—its deft observation and its generosity.

I loved the way you brought in muscle memory with learning Bill Monroe and then later used it to describe Poxl making love to Françoise and then remembering it later. Did you know that you would use this musical part of yourself or did it just come up as something fortuitous?

It’s funny—there's the book you intend to write, and then there’s the book it becomes by necessity. For years I’d chosen to have Françoise a painter. My writerly desire was that there be a through line: Poxl’s mother and the painter she’s having an affair with, Françoise and her characteristic ability to see, and then what happens to her later in the war (no spoilers here). But somehow I couldn’t pull it off—technically I didn’t know enough about painting. That was part of it. But also it felt a little too thematically neat—like something you’d find in a novel, not something from life. So I had to give her something else to do.

After months of flailing around it hit me—just give her something you know about. I spent much of my 20s trying to be a semi-professional bluegrass mandolin player, and I still go to jams or help people out on records from time to time. At first that music seemed like it wouldn’t fit—it’s so American. But in doing some homework I saw that between Rotterdam being the biggest port in all of Europe, and these early bluegrass records coming out in the ’30s and ’40s, it was both viable—and a surprisingly good fit for Françoise, her character. So there she was, with a friend from the brothel, playing mandolin and guitar.

In her New York Times review of your book, Michiko Kakutani mentioned the Brian Williams story in relation to Poxl’s fabrication, and she probably won’t be the last. Bill O'Reilly’s name will likely come up, too. What will your strategy be when this oddly well-timed coincidence comes up? Do you want to take Brian Williams out for a nice dinner? I think his schedule is pretty open these days.

I’ve got two answers for this one, I think. First, I’m not sure that it’s a coincidence, quite. The seed of this book came in a moment when there was a spate of memoirs and reportage unveiled as different kinds of frauds: James Frey, then Jayson Blair, then JT LeRoy, then more. Just as I was leaving a job at Esquire, there was the case of this Native American memoirist Nasdijj, who’d written a number of successful memoirs—but turned out to be a white guy named Tim Barris. And that’s not even to mention all the false Holocaust memoirs, first among them the one by Swiss memoirist Binjamin Wilkomersky—the critic Ruth Franklin has written a whole excellent book on them called A Thousand Darknesses. I did wonder when I started if these were somehow of a moment, or if they were some atavistic, eternally recurring fact. I think I’m falling on the side of the latter. So I wanted to look at how trauma, fear, all kinds of motives can skew both how we tell a story, and how memory can shift over time—W.G. Sebald, again, is our great bard of that subject.

Part of me feels far more generous to Brian Williams than, say, the people at NBC seem to. I want to be very careful here—I’ve read the responses the soldiers who were on the helicopter that was hit had to his conflation of events, and I’m truly deferential to them, and their families, and their concerns. At the same time, in looking at how the Williams thing developed, it seems far more complicated than it’s been treated. In his initial report, you can hear how he says they were following a helicopter that took RPG and gunfire. How scary must that have been? If the D Train ahead of you one morning took gunfire, wouldn’t you be frightened almost as if it happened to you? Mightn’t your brain even conflate facts, allow you to misspeak in conversation? Years later his story changed, he conflated facts, and it’s not for me to say why. I’m not a news commentator. But I would say that trauma and fear can clearly affect our memory, and even if not, it affects how we narrate. When you’re asked to speak in front of people as much as a person like Brian Williams, stories must change in inflection and affect all the time. As I say: It’s not quite for me to say what the response should be. I only mean to say it feels somehow true—and somehow just the kind of emotional response I was trying to look at in a complicated way for Poxl West.