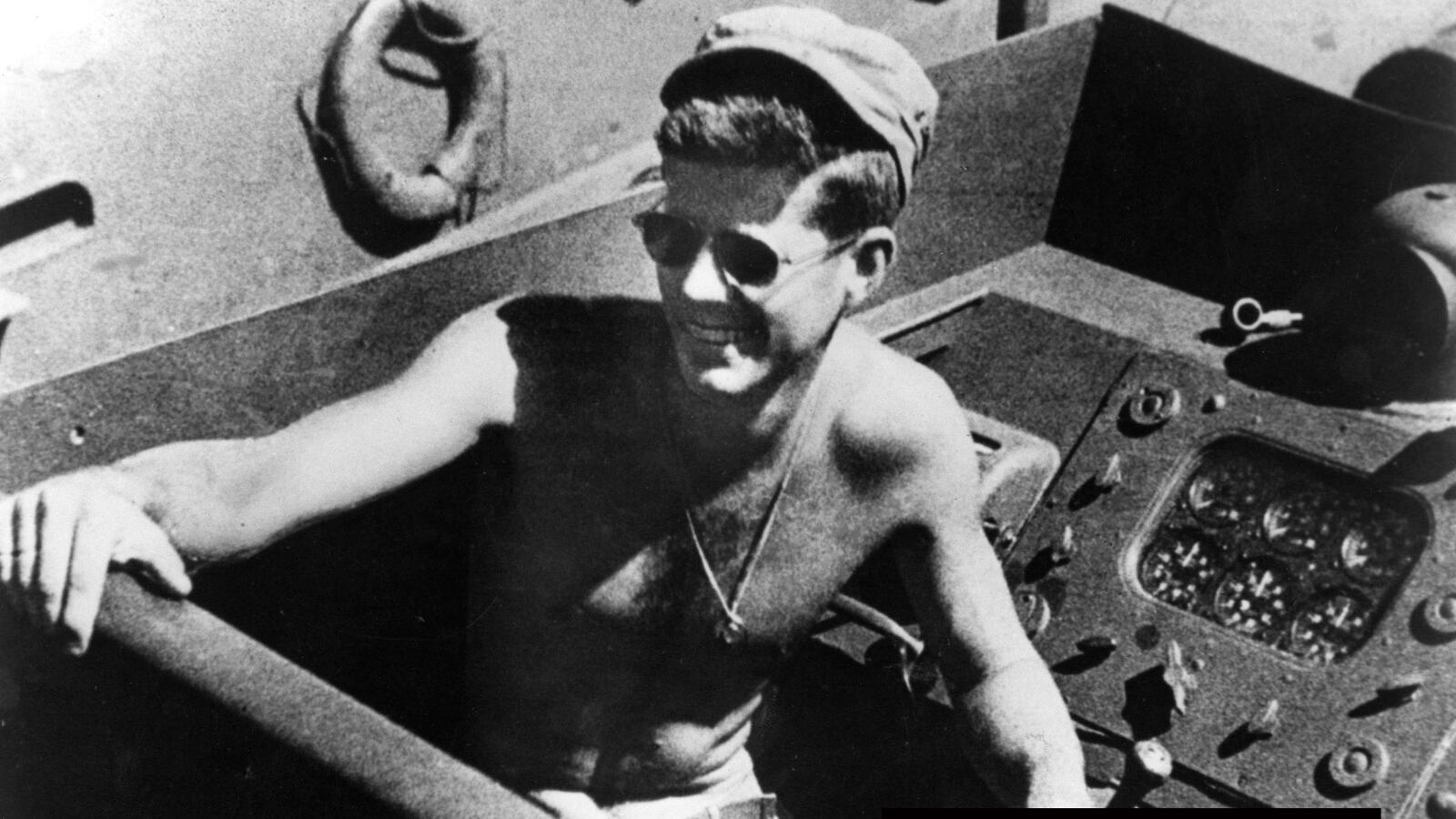

In 1941 and 1942, John F. Kennedy had an intense romantic affair with Danish journalist (and Hitler’s guest during the 1936 Olympic Games) Inga Arvad, who was married at the time. The affair ended when Kennedy went to the Pacific to serve during World War II, and in 1943 he became a war hero after his boat, PT-109, was rammed by the Japanese, and he rescued his crew by towing them with a life-jacket strap clenched between his teeth. Shortly after, he wrote one of his most candid letters to Arvad, whom he nicknamed Binga.

Dear Binga,

The war goes slowly here, slower than you can ever imagine from reading the papers at home. The only way you can get the proper perspective on its progress is put away the headlines for a month and watch us move on the map. It’s deathly slow. The Japs have dug deep, and with the possible exception of a couple of Marine divisions are the greatest jungle fighters in the world. Their willingness to die for a place like Munda gives them a tremendous advantage over us. We, in aggregate, just don’t have the willingness. Of course, at times, an individual will rise up to it, but in total, no….Munda or any of those spots are just God damned hot stinking corners of small islands in a group of islands in a part of the ocean we all hope to never see again.

We are at a great disadvantage— the Russians could see their country invaded, the Chinese the same. The British were bombed, but we are fighting on some islands belonging to the Lever Company, a British concern making soap. I suppose if we were stockholders we would perhaps be doing much better, but to see that by dying at Munda you are helping to secure peace in our time takes a larger imagination than most possess….The Japs have this advantage: because of their feeling about Hirohito, they merely wish to kill. An American’s energies are divided: he wants to kill but he also is trying desperately to prevent himself from being killed.

The war is a dirty business. It’s very easy to talk about the war and beating the Japs if it takes years and a million men, but anyone who talks like that should consider well his words. We get so used to talking about billions of dollars, and millions of soldiers, that thousands of casualties sound like drops in the bucket. But if those thousands want to live as much as the ten I saw, the people deciding the whys and wherefores had better make mighty sure that all this effort is headed for some definite goal, and that when we reach that goal we may say it was worth it, for if it isn’t, the whole thing will turn to ashes, and we will face great trouble in the years to come after the war.

I received a letter today from the wife of my engineer, who was so badly burnt that his face and hands were just flesh, and he was that way for six days. He couldn’t swim, and I was able to help him, and his wife thanked me, and in her letter she said, “I suppose to you it was just part of your job, but Mr. McMahon was part of my life and if he had died I don’t think I would have wanted to go on living.”

There are many McMahons that don’t come through. There was a boy on my boat, only twenty- four, had three kids, one night, two bombs straddled our boat and two of the men were hit, one standing right next to me. He never got over it. He hardly ever spoke after that. He told me one night he thought he was going to be killed. I wanted to put him ashore to work. I wish I had. He was in the forward gun turret where the destroyer hit us.

I don’t know what it all adds up to, nothing I guess, but you said that you figured I’d go to Texas and write my experiences. I wouldn’t go near a book like that. This thing is so stupid, that while it has a sickening fascination for some of us, myself included, I want to leave it far behind when I go.

Inga Binga, I’ll be glad to see you again. I’m tired now. We were riding every night, and the sleeping is tough in the daytime but I’ve been told they are sending some of us home to form a new squadron in a couple of months. I’ve had a great time here, everything considered, but I’ll be just as glad to get away from it for a while. I used to have the feeling that no matter what happened I’d get through. It’s a funny thing that as long as you have that feeling you seem to get through. I’ve lost that feeling lately but as a matter of fact I don’t feel badly about it. If anything happens to me I have this knowledge that if I had lived to be a hundred I could only have improved the quantity of my life, not the quality. This sounds gloomy as hell. I’ll cut it. You are the only person I’m saying it to. As a matter of fact knowing you has been the brightest point in an already bright twenty-six years….