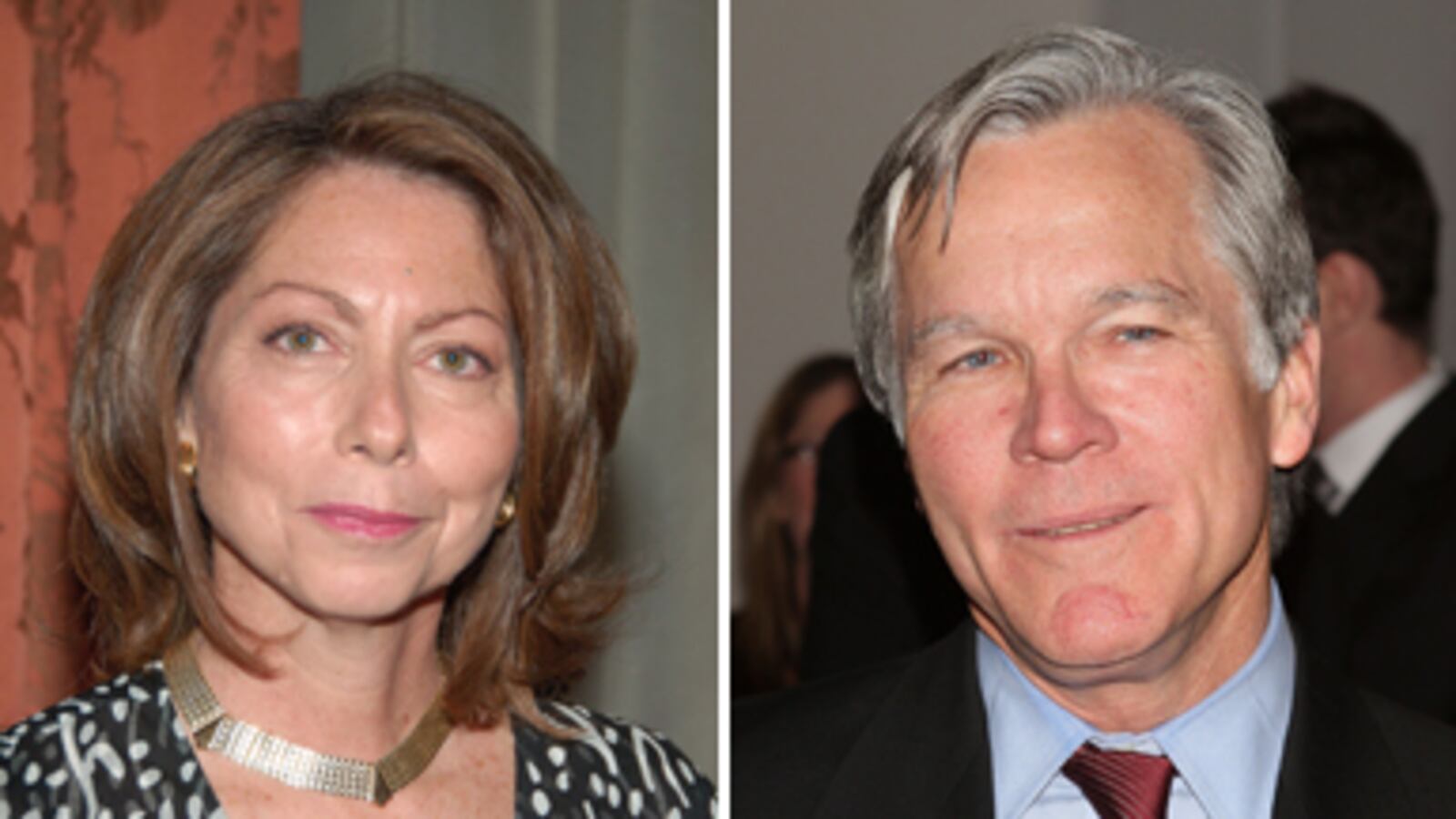

A year ago, as Jill Abramson recalls it, Bill Keller took her to dinner and told her he was thinking of stepping down as executive editor of The New York Times.

That, of course, would mean that Abramson, Keller’s deputy for eight years, would have a shot at his coveted job. But her reaction was instinctive.

“I said, ‘That is ridiculous.’ He seemed completely passionate about his job and still getting a kick out of it. I talked him out of having those thoughts, and his wife did, too.”

Keller recalls his managing editor and his wife, Emma Gilbey Keller, putting it this way: “They said you can’t leave until the digital stuff is finished.” By that he meant the integration of the paper’s print and digital newsrooms and the creation of a gradual paywall for online content. He told publisher Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. of his decision a month ago, saying it was best to leave when things were going smoothly. But he acknowledges a twinge of regret during the newsroom announcement Thursday.

“You’re surrounded by all these people. Your life has been entangled with theirs in 100 different ways. You’ve collaborated on stories with them. You’ve been with them when their kids were sick. You’ve tried in some cases to get them out of dangerous situations. You’ve argued with them. You’ve cut their budgets. Realizing how much they mean to me gave me a lump in my throat.”

Still, he says, “you can overstay your welcome at the pinnacle.” Keller will return to fulltime writing and launch a column for the new Sunday opinion section.

Abramson will become the first female executive editor in the 160-year history of the Times, but she downplays the importance of that milestone.

“I’m hard-charging and a competitive news person, but this is a big place,” she says. “Most of the great things we publish don’t pop out of editors’ heads, they bubble up from the reporters.”

When prodded, she adds: “I certainly feel a sense of history and I’m acutely conscious that I stand on the shoulders of a lot of other women.” In fact, Abramson was thinking of leaving the paper a decade ago—she was Washington bureau chief and felt she was being mistreated by Executive Editor Howell Raines—until she got a call from company executive Janet Robinson, now the company’s president.

Abramson deflects criticism that the Times newsroom is liberal: “Journalists in the newsroom play it straight.”

“You will quit over my dead body,” she recalls Robinson saying.

The sisterhood was also at work in 1997 when Abramson was deputy Washington bureau chief at The Wall Street Journal and met Maureen Dowd at a party. The Times columnist asked if she knew any good women that her paper could hire.

“I kind of said, ‘What am I, chopped liver?’” Dowd got the ball rolling.

Some Times insiders say the blunt-spoken Abramson was getting impatient with the long apprenticeship. Indeed, the Harvard graduate was recruited as a candidate to run the Nieman Foundation. But rather than using the approach as leverage, she told no one at the paper except Keller before declining to be considered.

Abramson, 57, has long been viewed as Keller’s heir apparent, but there was a plausible rival in the person of Dean Baquet, the Washington bureau chief, who moves up to managing editor. Baquet was a dynamic editor of The Los Angeles Times before resigning amid the wreckage of Tribune Co. budget cuts. He may still become the first African-American editor of The New York Times.

Some staffers wonder about Abramson’s forthcoming partnership with Baquet, given that the two sometimes clashed as part of the usual friction between the New York and Washington offices.

Keller, 62, had been expected to stay in the job for another couple of years, so the timing came as a surprise.

Abramson says a top priority is retaining talent at the Times, which has had a number of recent defections. “Sometimes I can feel like I’m playing whack-a-mole against many organizations, from the Huffington Post to Bloomberg to ESPN. People are hiring up and they’re coming for stars at the Times. Rooting people here, being out talking to staff, making them feel we are guardians of their full careers, is more of a challenge.”

Keller, a Pulitzer-Prize winning foreign correspondent, was managing editor in 2001 when he was passed over for the top job in favor of Raines. He went into what he calls “happy exile” on the editorial page, but Sulzberger gave him the job two years later after Raines was forced out over the Jayson Blair fabrication scandal and his imperious management style.

“It sounds like a smart-alecky thing to say, but there’s some advantage to having an easy act to follow,” Keller says. “After a period when people felt badly treated, I was welcomed into the newsroom in a way I might not have been if I’d followed Joe Lelyveld,” the previous editor. “When you try to impose an autocratic leadership style, over time you do serious damage. It didn’t take an advanced degree in management to let the place heal.”

Keller recalls a number of highlights, such as publishing stories on the Bush administration’s domestic surveillance program over the president’s objections. But he is equally proud of “avoiding debilitating budget cuts,” though there were some layoffs, and “organizationally, culturally, psychologically bringing us into the digital age.”

Keller’s rockiest period came in 2005, when Times reporter Judith Miller was jailed for 85 days for refusing to testify in the leak investigation involving CIA operative Valerie Plame. Keller, who had defended Miller, later wrote in a memo that she seemed to have misled the paper about her involvement and that he didn’t fully understand her role in the case.

The job of defending the paper now falls to Abramson. She deflects criticism that the Times newsroom is liberal, saying whatever the paper’s editorial philosophy, “journalists in the newsroom play it straight.” But she acknowledges that “there’s a lot of cynicism toward the media. It does worry me.”

Abramson’s husband, sister, and two children joined in her in the newsroom for the announcement. In what is undoubtedly a first for a Times executive editor, her 25-year-old son has a record label, manages several groups and plays in a rock band. She caught his act last week in Brooklyn—“and I was the oldest one there.”

Howard Kurtz is The Daily Beast and Newsweek's Washington bureau chief, and writes the Spin Cycle blog. He also hosts CNN's weekly media program Reliable Sources on Sundays at 11 a.m. ET. The longtime media reporter and columnist for The Washington Post, Kurtz is the author of five books.