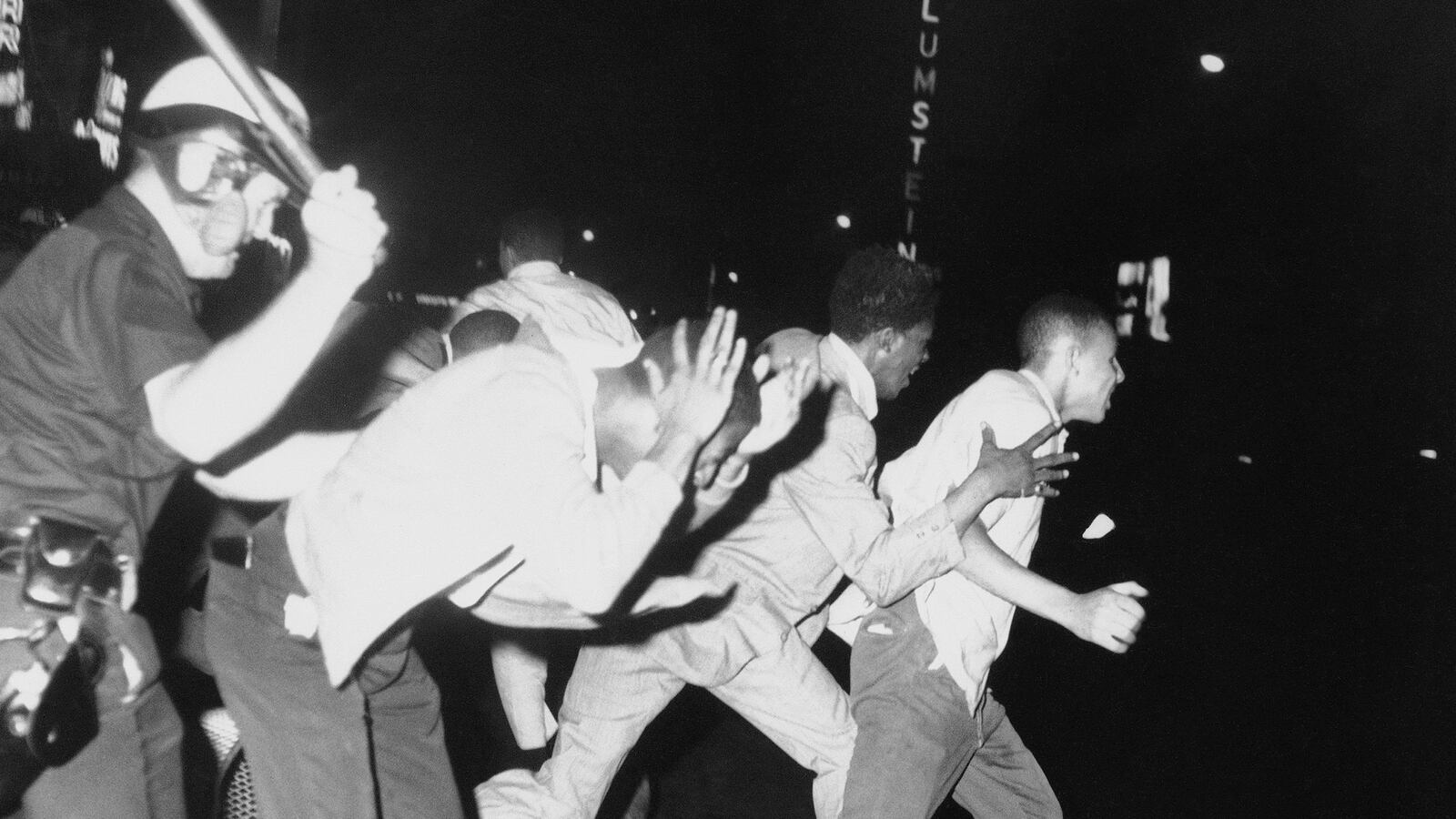

Editor’s note: On July 16, 1964, NYPD Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan killed 15-year-old James Powell, an African-American kid from the Bronx. What followed were six nights of rioting that roiled Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. More than 4,000 rioters took part in the mêlées, which left stores looted, 118 people injured, 465 arrested and one rioter dead. Legendary New York Herald-Tribune columnist Jimmy Breslin wrote the following column on July 20, and it is reproduced with his permission.

THE shirtless children ran through the gutters and played with the broken glass and the dull brass cartridge shells from the riot of the night before. The flat sky was an open oven door and its heat made people spill out of the tenements and onto the stoops, or onto milk boxes set up on the sidewalk, and they sat and watched the children pick up the brass shells and pocket them as if they were prizes.

They watched the cops too. The cops were everywhere, four and five of them on a street corner, wearing white steel helmets, and the people of Harlem watched them and hated them yesterday afternoon.

“When I see a white cop, I can’t help myself, I just can’t stand looking at one of them,” Livingston Wingate was saying. “I’m supposed to be a responsible person and I try to rub it from my mind. But right now, when I look across the street here and see those white cops, I get disturbed. I just can’t stand looking at them.”

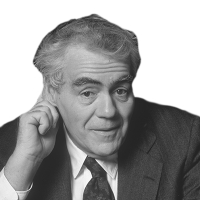

Wingate is an official. He is a lawyer who has worked for the government in Washington. He now is one of the major figures in running HARYOU-ACT, which has been formed to help young people in Harlem. When people of position talk the way he did, the trouble is bad. And yesterday afternoon, while everybody in Harlem waited for the sun to go down and night to cloak the streets and make moving around easier, you wondered just how bad it would become.

Some of them wanted to get at it in the daylight. The fire trucks had 129th Street, between Madison and Fifth, tied up during an alarm at 2:15 in the afternoon, and to make room for a hook and ladder coming through, the guy driving us pulled in to the curb in the middle of the block.

Right away, somebody moved off the stoop: a kid with a shaved head and a gold polo shirt. He was about nineteen and he went to another stoop, where three other kids were sitting. He said something to them and they looked at the car. Then they got up and came onto the sidewalk and the one with the shaved head walked across the street and spoke to a crowd on another stoop.

Then he came walking back, looking at the car; and when you stared back at him, his eyelids came down and made his eyes narrow.

“What are you lookin’ at, you big fat white bastard?” he said.

“Oh, come on, it’s too hot for this nonsense,” we told him.

“We’re goin’ to show you what’s nonsense,” he said. “We’re goin’ to stick some nonsense right into your fat white belly.”

A fireman, rubber boots flopping on the melting tar street, walked over from an engine. He had an ax in his hand. A new ax. Big, with a light yellow wooden handle. The kid with the shaved head didn’t even notice him. He just kept walking past the car and went back to the stoop where three waited for him.

“What the hell are you doing here?” the fireman said. “Don’t you listen to the newspapers?”

“We’re trying to get through.”

“They were stoning us last night,” the fireman said. “You don’t know what it was like here. They were trying to kill us. Get out of here if you got any brains.”

Then he went back to the truck. The other firemen came out of the tenement and climbed onto the trucks. There had been no fire and now the three trucks were starting to pull away.

“Hey, fat white bastard,” the shaved head called out. “Why don’t you stay around here till these trucks leave?”

“Oh, come on,” he was told.

Two trucks left, and then the hook and ladder moved by, and the minute it did, the guy driving us in the car pulled away from the curb and started up the block. The kids came out from both sides. They were walking at first, but then one of them ran and tried to get in the back door on the right-hand side, but now the car was moving too fast and he couldn’t make it and then, with the car heading up the block, you saw his bare black arm pull back and then come up and something came through the air at the car.

Whatever it was, it exploded when it hit the street behind the car. Who knows what it was? Molotov cocktails were all over the place Saturday night. Maybe it was nothing more than a firecracker. You couldn’t tell. If somebody snapped his fingers on 129th Street in Harlem yesterday afternoon, the noise made you jump.

It all came down to this in Harlem. All the talk and all the speeches and all the ignorance and all the history of this deep vicious thing of black against white which they classify under the nice name of civil rights came crashing down from the rooftops inside garbage cans. The symbol of a couple of hundred years of sinful history became a black arm pulling back and then coming around to throw something at a white cop.

And there seemed to be no way to talk to anybody. For a while the big main avenues of Harlem seemed quiet and police-state orderly yesterday afternoon the people sitting on the side streets with a bitterness which went right through you when you saw it in their faces.

There seemed to be nobody who could stop what everybody thought the night would bring.

At 4:15 p.m. we drove to the mount Morris Presbyterian Church with Judge James Watson to hear Jesse Gray address a rally. Gray is an irrational man who is a force in Harlem only because of the white press, which failed in its obligation to check out people it writes of. Publicity made Jesse Gray, and yesterday afternoon was to be his great chance for rabble-rousing.

Then Jesse Gray got up and this church turned into something you’ve never seen before.

“Before today is over, we’ll be able to separate the men from the boys,” Gray said when he got up.

“Only one thing can solve the problem in Mississippi, and that’s guerrilla warfare,” Gray said. “I’m beginning to wonder what’s going to solve the problem here in New York.”

He threw the line out into the hot airless church and he waited for the answer he knew would come. He got it.

“Guerilla warfare,” they shouted.

“Oh, my God,” Judge Watson said in the back of the church. “Oh, my God.”

It was a little before five o’clock on a Sunday afternoon. A long hot night was in front of everybody.