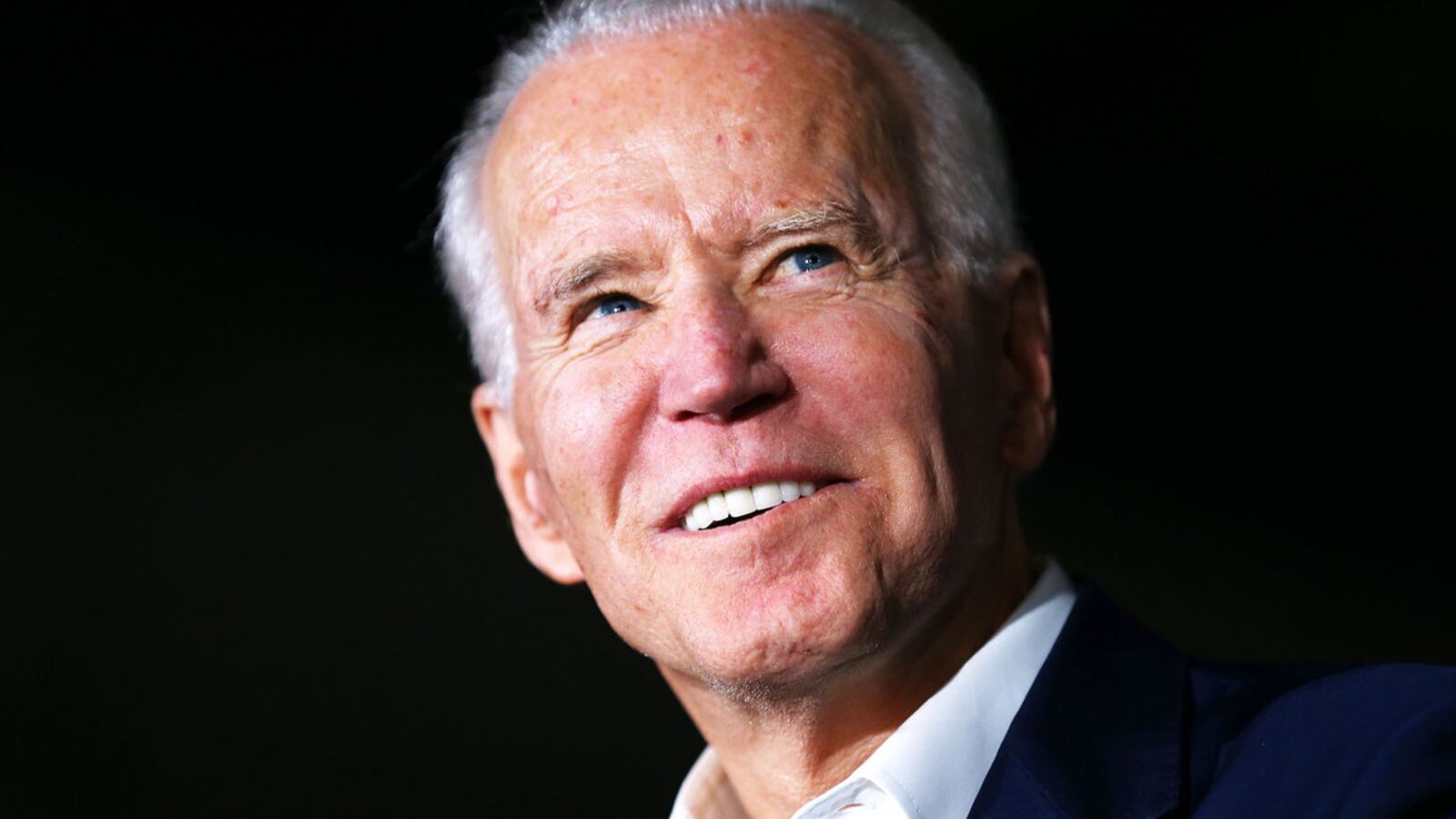

For the man who hopes to replace President Donald Trump at the helm of the federal government, the president’s fumble has presented an opportunity to fill the leadership void left by the president, who insisted that there are enough tests for the novel coronavirus, that the stock market is fine, and that all evidence to the contrary is a Democratic “hoax.”

“Let me be crystal clear: the coronavirus does not have a political affiliation,” former Vice President Joe Biden said in an address on Thursday afternoon in Wilmington, Delaware, remarks that effectively functioned as a rejoinder to Trump’s address to the nation from the Oval Office the night before.

“Protecting the health and safety of the American people is the most important job of any president,” Biden continued, adding that the U.S. government’s response to the pandemic “has laid bare the severe shortcomings of the current administration,” compounded by “a pervasive lack of trust in this president.”

If empty grocery store shelves, massive stock market sell-offs and the widespread suspension of public events across the country are any indication, Trump’s response to the pandemic has been seen as a disastrous failure of his administration to rise to meet the challenge of the moment. In contrast, Biden’s message emphasizing the importance of collaboration with global partners and local governments for a unified response to the novel coronavirus was well received—and is in keeping with his past actions during similar public health crises.

An analysis of Biden’s decades-long career as a lawmaker and a vice president shows that he has a mixed report card on issues relating to public health crises. Biden has won credit for his work during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), but occasionally gave in to public hysteria and scapegoating during other emergencies, such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic and swine flu.

The Trump campaign, eager to deflect from the perception that the president is out of his depth on an issue of grave importance, responded to Biden’s critiques by assailing the former vice president’s own record on public health issues, accusing him of having shown “terrible judgment and incompetence” in similar cases.

Biden’s campaign, however, is more than happy to draw contrasts between the former vice president’s past work during public health crises and Trump’s.

“Whether it was an early vote in 1987 authorizing critical funding for medication that prolonged the life of people with AIDS, his 1990 efforts passing the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Care Act, or his work as vice president helping lead the 2014 Ebola epidemic response, Joe Biden has exemplified throughout his career what disciplined, trust-worthy leadership grounded in science looks like—a sharp contrast with Donald Trump,” said national press secretary Jamal Brown. “That’s why Joe Biden released a plan this week to combat the global coronavirus epidemic. We hope President Trump will adopt it.”

As a senator and as vice president, Biden emphasized the importance of international cooperation and coordination in tracking and combating infectious agents, as evidenced by his repeated—and unsuccessful—introduction of the Global Pathogen Surveillance Act. The act would have created a biological threat detection system and improved the United States’ ability to detect, identify, contain, and respond to both pandemics and bioterror attacks.

“We should make no mistake: in today’s world, all infectious disease epidemics, wherever they occur and whether they are deliberately engineered or are naturally occurring, are a potential threat to all nations, including the United States,” Biden said upon the bill’s introduction in 2002.

In a report submitted by Biden urging the bill’s passage, the Delaware senator wrote that nations with underdeveloped healthcare systems were “weak links in a comprehensive global surveillance and monitoring network.”

“It is vital to give these countries the capability to track epidemics and to feed that information into international surveillance networks,” the report stated—a far cry from the Trump administration’s current policy of containment by way of involuntary quarantine.

In 2003, Biden hammered that point home during the outbreak of SARS, when the Chinese government attempted to cover up the illness’ origins and rapid spread.

“A comprehensive surveillance network might have picked up the unique symptoms of this epidemic earlier. It might have led to quicker diagnosis,” Biden told the Orlando Sentinel at the time, calling nations like China “weak links” in monitoring global disease that needed American assistance to prevent their spread.

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa—the most recent major public health crisis, and the only one to occur in the era of social media—Biden again stressed the inability of national borders to constrain the spread of disease, and called for international cooperation to fight the virus to the same degree that international cooperation was needed to fight the Islamic State or Russian aggression in Ukraine.

“Each one in its own way is symptomatic of the fundamental changes that are taking place in the world,” Biden said at the Harvard Institute of Politics in October 2014, one day after Trump—then a fading reality TV personality and self-described billionaire—tweeted on the United States to halt all flights from West Africa into the country.

Far from Trump’s isolationist response to disease, Biden warned that “threats as diverse as terrorism and pandemic disease” were crossing borders “at blinding speeds,” and said that such crises demand a global response involving more players “than ever before.”

“The international order that we painstakingly built after World War II and defended over the past several decades is literally fraying at the seams right now,” Biden, whose former chief of staff, Ron Klain, spearheaded the Obama administration’s response to the crisis and is currently advising him on the coronavirus pandemic, said at the time. “Take Ebola… a horrific disease that is now a genuine global health emergency. Our Centers for Disease Control, USAID and our military have taken charge of that world epidemic, [and] we are organizing the international response to this largest epidemic in history.”

But there have been exceptions to Biden’s “we’re all in this together” response to global public health emergencies. In those cases, either in public remarks or in Senate votes, Biden unintentionally fanned the flames of public anxiety and prejudice—the same accusations that have been lodged against Trump and other Republicans for referring to the novel coronavirus as “Wuhan flu” or a “foreign virus.”

In May 2009, fresh into his new role as vice president, Biden appeared on a popular breakfast show amidst growing anxiety over the nascent swine flu outbreak that he would “tell members of my family—and I have—I wouldn’t go anywhere in confined places now.”

“It’s not that it’s going to Mexico—if you’re in a confined aircraft and one person sneezes, it goes all the way through the aircraft,” Biden said on the Today Show, contradicting the government’s public stance that it was safe for healthy people to travel. “I would not be at this point, if [my family] had another way of transportation, [be] suggesting they ride the subway.” The Trump campaign has latched onto that statement, noting that Biden was later forced to walk back his comments.

But beyond his (somewhat characteristic) gaffe, Biden’s past challenges during public health crises were most notable in Biden’s response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a member of the U.S. Senate, at a time when public information about the virus and the syndrome was relatively limited and bigotry against HIV-positive people was rampant both in and out of government.

In 1987, in the runup to his first of three campaigns for the White House, Biden voted in favor of an amendment sponsored by Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC)—an infamous figure among activists fighting for the rights of LGBT people and people with AIDS at the time—that amended an appropriations bill to list HIV among “the list of dangerous infectious diseases that would prevent immigration to this country.”

The amendment was deeply unpopular with public health experts—when President Ronald Reagan endorsed the measure during an AmFAR dinner that year, the proposal had been met with boos and hisses from HIV/AIDS experts and medical health professionals—but passed the chamber unanimously.

Six years later, Biden joined 75 other senators in voting for Oklahoma Republican Sen. Don Nickles’ reauthorization of the ban on HIV-positive immigrants and tourists, then known as the “Helms Amendment,” against the wishes of President Bill Clinton, who had campaigned against the policy. The amendment’s passage as a rider on the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993 was considered a major embarrassment for Clinton, and the policy remained in place until 2009, when President Barack Obama lifted the ban.

Then-freshman Rep. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) was one of the few members of the House of Representatives to vote against the amendment in the House, though he did vote “yea” on the final conference report on the bill.

While Biden condemned proposals for quarantining those with HIV, requiring a broad public testing program 0r criminalizing the donation of HIV-positive blood—in a roundup of candidates’ positions on HIV in the St. Louis Dispatch in August 1987, Biden was quoted as saying that “quarantining AIDS victims would be an unreasonable violation of their basic civil rights”—some of the measures he did support were deeply unpopular with scientists and doctors.

But as public understanding of HIV/AIDS changed—and as major appropriations finally opened up fund research and treatment—so too did Biden’s approach to the crisis. In 1990, Biden was one of 66 co-sponsors of the landmark Ryan White CARE Act, which funded emergency assistance to areas disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic and has since become one of the most important funding mechanisms for the development and implementation of HIV/AIDS treatments.

In the 2000s, Biden used his perch on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to help advance and later reauthorize legislation that extended American assistance to anti-AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis initiatives in the developing world, co-writing the legislation with Sen. Dick Luger (R-IN). President George W. Bush, who signed the bill into law, thanked Biden by name for delivering the legislation to his desk.

“I want to thank the members of the House and the Senate who are here,” Bush said. “Bill Frist has been a leader on this issue and he, along with Senator Richard Lugar and Senator Joe Biden, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, delivered.”