In 2007, when President George W. Bush sought to create a pathway to citizenship for the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States, his push ended with a whimper, a Hail Mary pass by an unpopular second-term president whose approval ratings were already on the verge of collapse.

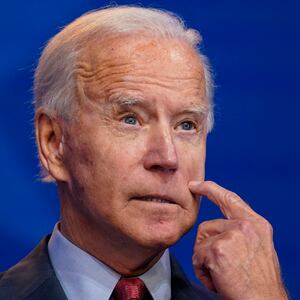

Nearly 15 years later, President Joe Biden is wagering that the increasingly apparent unviability of the current system—as well as the disastrous immigration policies of his predecessor—may make comprehensive immigration reform a palpable possibility for the first time in decades. On Thursday, Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) and Rep. Linda Sánchez (D-CA) are set to introduce the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, Biden’s wide-ranging bill that would provide millions of undocumented people the ability to earn U.S. citizenship.

“The American people know that our immigration system is not working the way that it should,” a Biden administration official told reporters on a briefing call ahead of the bill’s introduction. “The legislation is a common-sense approach to solving the immigration challenges that we’re facing… We’re taking a new and more comprehensive approach, whereas the prior administration was solely focused on the wall and did nothing to address the root.”

The bill, coming nearly a month after Biden’s “Day One” promise, would be the greatest expansion of access to citizenship for undocumented immigrants since President Ronald Reagan granted amnesty to more than 3 million undocumented immigrants in 1986. The legislation would allow undocumented people living in the U.S. to apply for temporary legal status, with a five-year window for obtaining a green card—permanent legal residence—for those who pass background checks and pay back taxes. For those brought to the U.S. as children, immigrant farmworkers, and those who have Temporary Protected Status, green card eligibility would be immediate.

The legislation would also streamline naturalization for a variety of current visa holders, and permanently prohibit barring immigrants from entry into the United States based on their religion.

But like Bush’s doomed proposal years ago, Biden’s bill has already drawn criticism from both immigration hawks and immigrants-rights advocates, as well as skepticism that legislation so sweeping has any shot of passage through Congress.

“We have lived through many broken promises on immigration,” Erika Andiola, chief advocacy officer of the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), said in a statement. “Comprehensive immigration reform and the DREAM Act have failed in Congress time and time again, even when Democrats had the majority. Passing legislation this year will be no easy task given the extreme wing of the Republican Party and moderate Democrats who want to appeal to Republican supporters.”

Critics of the plan, meanwhile, say that Democrats’ razor-thin margin of control in the U.S. Senate means that the legislation is a nonstarter.

“The bill that Joe Biden sent… I think, will be dead on arrival,” Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) said on Fox News last month, once details of the bill’s main components were released by the administration. “It’s far to the left of any immigration bill that Congress has considered.”

Administration officials said that the bill’s expansive nature is appropriate to the size of the issue, particularly after four years of hostility by the Trump administration to any changes to the immigration system that didn’t result in making access to the United States more difficult, expensive, and limited.

“You have to address all aspects of the system to fix it,” one administration official said, when asked whether Biden would consider breaking up the bill in order to help facilitate its passage through Congress. “[Biden] was in the Senate for 36 years and he’s the first to tell you that legislative process, you know, can look different on the other end than where it starts. He still thinks that these are all the elements that should be in the package, but again, is willing to work with Congress to get something done.”

But immigration advocates, wary of Biden’s slower-than-hoped-for rollbacks of his predecessor’s policies on the “Remain In Mexico” and family separation policies, say that those assurances are cold comfort for past failures to allow the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States to pursue legal status.

“The path to victory on legalization is clear: Ending the filibuster, legalizing as many people as possible through the next reconciliation package, and using executive action are all tools that can be used to protect the immigrant community without compromising anyone’s humanity,” Andiola said. “It can be done, and it must be done.”