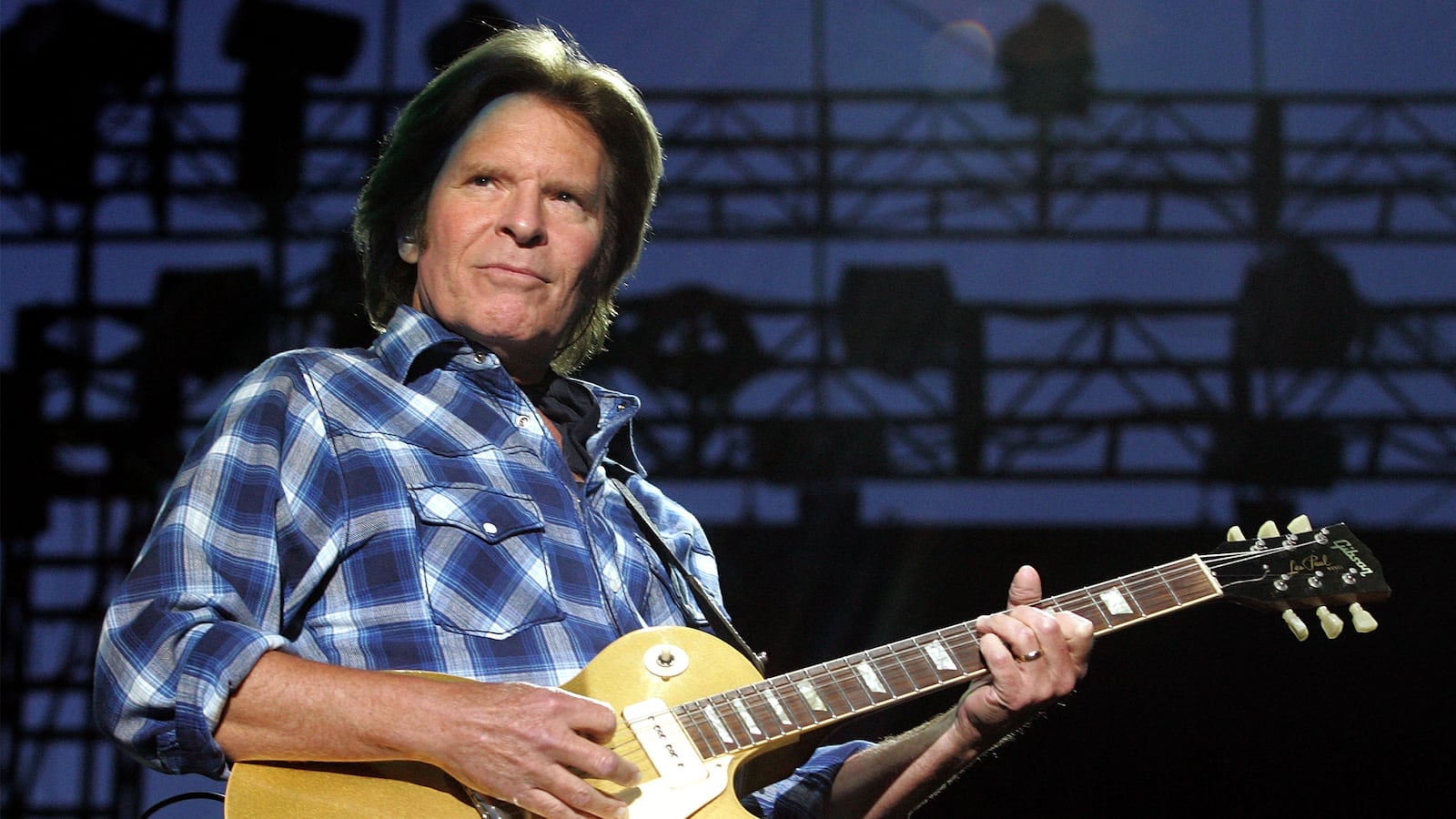

John Fogerty is ready to move on.

Despite having penned nearly a dozen Top 10 hits, sold millions of records, and earned a spot among the upper echelon of American singer-songwriters, the creative force behind Creedence Clearwater Revival has faced decades of public turmoil with ex-bandmates, vicious lawsuits with record labels, estrangement from his brother, and a battle with alcoholism.

His autobiography—titled Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music, after his iconic 1969 anti-war anthem—seeks to tell his life’s story. Hopefully, he believes, people will read through its pages and no longer feel the urge to ask him the same questions he’s faced for thirty years now.

Does he regret the acrimonious split from his brother Tom and fellow bandmates Stu Cook and Doug Clifford? Why wouldn’t he perform with them at the band’s Hall of Fame induction? How does he feel about the latter two still touring on the “Creedence” name? It’s all there in the book.

The Daily Beast talked to Fogerty about the book, his storied career, overcoming his personal struggles, and whether the political warnings of “Fortunate Son” still ring true today.

For decades, you’ve been painted as a bit of a recluse. Reading the book, I was struck by how forthright you are about some of the darkest periods in your life. What made you decide to do this tell-all of sorts?

The simple answer would be meeting my beautiful wife, Julie. She just made me feel better about life in general. I went through a long, dark period because of the shenanigans of the music business and some of the events that happened with my own bandmates from the old days in Creedence. Writing the book, I knew I just wanted to be very honest. I’ve already lived my life’s story, so I wanted to be completely honest and open, with no hidden closets because that way I would feel that everybody—my own kids included—would see it all there and from then on I could tell people when they had a question, “Well, it’s in the book.”

You’ve always been painted in the media as the curmudgeon—especially after the 1993 Hall of Fame incident. Why do you think the media has been so quick to eat up the negative stories from Stu Cook and Doug Clifford?

I don’t feel like one of those athletes that start off on the wrong foot and then they’re in the doghouse from then on out. I feel like some of the things that happened between us were pretty difficult to understand because there was a lot of intrigue. And because it was a complicated story, the newspaper wouldn’t be able to put all that material into one article. And so I would end up sounding like some guy trying to plead his case, and you end up, you sound like you’re shouting. I know somewhere, maybe around 2000, I saw an article about myself in a magazine, and thought, “Wow, John, that doesn’t look very good. You’re trying so hard to say what’s important to you but it doesn’t come off, there’s just not enough time, and therefore you just end up looking like a crazy person shouting at the top of your lungs.”

The biggest political statement of your career was obviously “Fortunate Son.” It seems like we’re still dealing with the problems you addressed—perpetual war, corrupt and nepotistic leaders, diminished hopes. In some ways, Donald Trump embodies the “fortunate son” you railed against 46 years ago, no?

When Donald Trump first announced he was running for president, I thought that’d be like an eyeblink. This has happened before in our history where sorta off-the-wall folks will announce their candidacy and then, as we learn more about them, it becomes silly and they eventually leave.

But what’s fascinating about the Trump candidacy is not only that he became one of the players but that he became the highest-rated. I find that surprising at first, but now you wonder: What is going on here if that many people are still supporting his candidacy? I kinda thought we all knew what there was to know about Donald Trump. It is surprising to me that at this stage in his life he can say things that shock people.

I happen to be a lifelong liberal, I’m certainly not going to be voting for Donald Trump, but I find the candidacy and that story fascinating on the landscape of American politics.

I’m also fascinated and I am very happy that Jeb Bush didn’t find it as easy as his family probably thought it would be to have another Bush up in the higher ranks. He just doesn’t look very appetizing and most people feel that kind of way. I’m not a Republican or a conservative, so it’s not something that really affects me. I do find [Trump] especially fascinating and the rest of it is the same old stuff, as far as I’m concerned.

A few years ago, you told Marc Maron, “I realize I’m kind of a lot more like some kind of libertarian or something.” Do you still feel that way?

Well, I don’t entirely know their philosophy. I just feel that I’m pretty liberal in the Pete Seeger tradition. I still feel that way. It isn’t that I’ve gotten old and, oh, now I want to protect myself or my pocketbook. I’m always surprised, though. I’ll be riding in a car and I’ll think, “You know, John, economically you’re more in a place where all those Republicans are.” And I go, “Oh, well, yeah, but that doesn’t matter. I don’t like the Republican point of view.”

But I do try to keep an open mind to what people are saying. I definitely can understand how some folks think that Democrats only raise taxes. And it certainly looks that way a lot of the time. I think the thing I’m more tempered with is that our system, our government, our politics is so complicated. For instance, let’s use Mr. Obama as a good example. Boy, there was so much euphoria when he was first making those wonderful speeches and drawing big crowds in 2008. It all sounded like the new Jesus or something, and then he gets elected and us liberals are waiting for this cool stuff to happen. And then the first thing that happened was that he got very quiet about the stuff he said when he was getting elected. We’ve certainly seen a lot less of him.

The other thing is that as you get older, you start to realize, hmm, the candidates on both sides start to look more and more similar than when you were maybe 22 years old. The stuff they end up doing after they get elected starts to look more like each other than the difference that you once thought existed.

I look back to 2008 and Tim Geithner was the guy Obama selected for his cabinet and it turned out he was a big Wall Street guy who hadn’t paid his taxes for many years. Oh, that should tell you something. It’s exactly like what the other side of the aisle does. Maybe that’s symbolic.

A touching part of the book is when you describe how terrified you were of becoming a father again at age 46. “Oh my god, am I gonna be a good daddy?” you recall asking yourself. You talk a great deal about finding love years after your big success.

Yeah, I fell in love with Julie. And that was the best thing that ever happened to me. I didn’t really realize until much later that it had been always what I dreamed of. Before I knew Julie, I didn’t realize it; I thought I was a normal person looking for career. But what was far more important to me was falling in love and having love. And so when we had kids, I worried because I was a little bit older. But it turned out that I didn’t have to worry. It’s one of the greatest feelings in life, being a father. And, of course, in a lot of ways, it helped with my own healing. It helped me become a better person and get to a better place where I didn’t really worry about bad things.

That same section of the book describes your battle to kick alcoholism, which coincided with a long bout of self-doubt surrounding the recording of your Grammy-winning record Blue Moon Swamp. Why is it that successful artists, rock legends even, can suffer from so much self-doubt?

The short answer I think is the psychological torment of [Fantasy Records president and one-time rights holder to Creedence tunes] Saul Zaentz tormenting me and me thinking it would eventually be resolved. But it was never going to happen. He was a bad person. So he was running me through the legal system with all his lawyers, and while I was in it, I thought I was going to make some headway, but it turned out he was playing with me. Because he’s not me. He never cared. The light never went on in that guy’s head. All he cared about was cheating other people, acquiring other people’s money, and having some success in a public career. I have a bit of pity for people like that, but he certainly wasn’t getting anything out of life.

So there was a lot of scar tissue in my soul, and that was getting in the way of creativity. So when I had self-doubts about recording Blue Moon Swamp, it was—yeah, I can put together some rhyming words and make some kind of jingle or ditty, but it wasn’t going to be at the heart of who I am. And that was very frustrating. I found there were so many layers of scar tissue or protection or armor that I couldn’t get into my own heart where that innocent kid of 22 who wrote “Proud Mary” was living. That was so hard.

In the book, I tried to describe the idea that, frankly, I’d rather go digging around in some other guy’s crap because it wouldn’t be so personal. And when I started digging around in my own baggage, it gets very uncomfortable. You see a lot of bad memories and you confront a lot of times that you were being a jerk or coming off as mean, even though you weren’t trying to do that, you were just so inept. So writing songs, to me, is digging through your own layers. And I would go down in these layers of my soul and not find a very nice guy.

It seemed to be my own therapy, meaning I felt I had to instinctively go through that if I was ever going to be any good again; if I was ever gonna be that true artist again. But a lot of my recovery came from talking with Julie and having her be real with me. I feel that I’m really enjoying my life with Julie and my family because of her influence.

I think a lot us can get into moments where we’re flying down the road, our shirttail blowing in the wind because we’re moving so fast, and if you’re not careful you lose yourself and you lose the true connection with your soulmate. But Julie’s grounded, so we manage to keep it grounded most of the time.

Now obviously there’s no love lost between you and the surviving bandmates, but do you think you could have swapped them out and just as easily scored so many hits?

If I had gotten other people to record at the same, could I have found success? Yeah, I think so. I could’ve found out how to do it with other people. But that’s hypothetical. And I don’t need to live in some hypothetical place.

The real answer is, of course, the way they played on the records is theirs. I wish everybody had lived there; I wish everybody had been comfortable to just accept that. But a lot of the attention in the band came from the other guys trying too hard to be hip, to be seen like The Beatles, let’s say. I know there was this great need from the other guys to be seen as doing the same things I was doing, and that wasn’t the way it actually was. I wasn’t trying to be hip, though. I wasn’t embarrassed to have a Top 40 hit. But they allowed that whole underground hippie FM radio, “let’s smoke a reefer together” mentality to color how they viewed themselves. And that caused a lot of the tension.

Speaking of The Beatles, a WFMU radio host once described Creedence as the “American Beatles.” It’s an intriguing comparison, especially considering how many hits you had and how uniquely American the music was. How do you feel about that comparison?

Oh, it’s very flattering. It’s a great honor to have people speak of you that way. One of the classic rock syndromes over the years, though, is you’ll hear a band with a one-hit record, and they’ll say we’re bigger than The Beatles. I’ve seen that happen a few times since 1966, and I get a chuckle out of it because no one will ever be The Beatles. They are completely separate from anyone else. The creativity at work in that band with everyone being songwriters and having big personalities—they changed the world. And I don’t think anyone can lay claim to anything close to that.

But for me, it’s an honor, obviously, but I don’t let that stuff deter me. As far as having an idol early on, I certainly was trying to emulate The Beatles. That’s how you should do it, folks. Look at all these great songs they’re writing and putting on the radio. That’s something I was trying to accomplish in my own meager way. They did it like no one ever did it before or since.

You were just a kid from the Bay Area who somehow had an uncanny ability to channel the swampy, rootsy elements of the South in a very authentic and cinematic way. When you listen to “Born on the Bayou,” you can see the bayou and feel the oppressive humidity. When you hear “Proud Mary,” you can envision the riverboat. How did you develop that undeniably Cajun-sounding voice?

The really true answer is I don’t know. Could it be reincarnation, maybe? I don’t know. The less mystical answer is that I grew up loving the South, having seen it through American culture. I was just absorbing everything and was fascinated by it.

Most of the records I grew up with were by Southern artists. I remember going to the very first Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony [in 1986], and I determined that all 10 of the first induction class were from the South. And their music, and American music, was very Southern by nature. I remember sitting there, at the table, looking at all the posters on the wall, and thinking, “Yep, I rest my case. It’s right there up on the wall.”

Of course, I was also fascinated by Southern literature like Mark Twain, Tennessee Williams; and movies and cool people in our culture at the time like Elvis. The folktales like Uncle Remus. I gravitated to all of it. I consumed. And it ended up building a place inside of me that I was able to refer to when it came time to write my own songs.

Did you consciously think about that influence while writing?

When I was thinking about, say, “Born on the Bayou,” it wasn’t contrived.

I remember during the “British Invasion,” the record labels originally named us The Golliwogs, and kept trying to make us into some kind of hip English thing, like, [mimics accent] “How about if you put a British accent on there.” Now that was contrived. That was a very obvious synthetic thing, and I think all of us hated that Golliwog period in our young music life.

Contrast that with how there’s a whole long story how I’d gone to get my little songwriting book, and then months later, being on the trail of a pretty good song, looking at my book, and I saw the title “Proud Mary” and, almost instantly, out jumps this song about Mississippi riverboats. Not only was that not contrived, but that was my first really great song and I was overjoyed that this thing was so wonderful. That’s how it resonated with me. To me, it was like discovering the best ice cream ever made.

Before we go, are there any modern songwriters you see in yourself? Anyone you really admire right now?

Oh, Ed Sheeran. I think he’s a great, great songwriter. I also like Pharrell Williams right now. He does it kind of differently. I don’t necessarily know everything he’s done, but he has a strong inner sense of who he is and what he likes to do. I like that.