Let’s assume that the future and the past hold hands across the present. Let’s assume that the present tense is crisscrossed with throbbing veins of information about the past and the future. (Maybe that’s what makes it so tense.)

I’m OK with that. Are you?

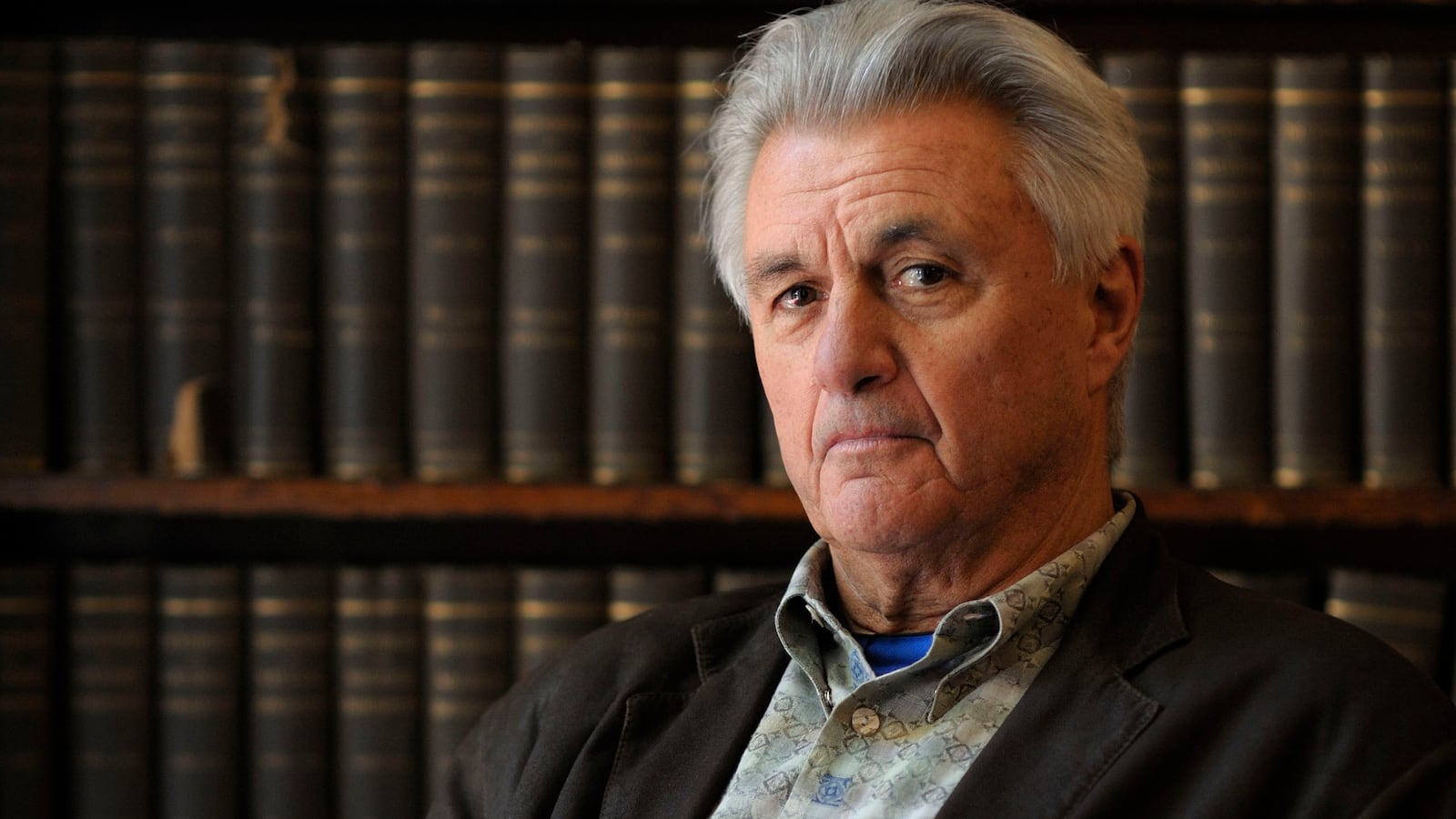

John Irving plays with time and space in Avenue of Mysteries, his 14th novel—he always has. Irving is a New England storyteller (long, dark winter nights), but there is more at stake this time. The characters enter a reader’s bloodstream, lodge in the DNA, whip up the imperative to learn more about living and seeing. Relax the tight grip of the will that smothers everything in its path.

Fourteen-year-old Juan Diego and his sublime, past and future seeing 13-year-old sister, Lupe, are dump kids. They scavenge and sort in the dump outside Oaxaca. Their mother, Esperanza, is a prostitute and the man who takes care of them, Rivera, may or may not be their father. These are miracle children. Juan Diego has taught himself to read (mainly the books of religious history discarded by the Jesuits in town) and speak English; Lupe reads minds and speaks in a voice that her brother must translate.

A Jesuit priest, Father Pepe, discovers Juan Diego, the “dump reader,” and Lupe and brings them to the orphanage. We used to say “fast-forward” when time did not march in a linear way, or “back at the ranch,” when we were being asked to cast our minds back to another place, but in Avenue of Mysteries we readers live Juan Diego’s life all at once, without apologetic, qualifying phrases.

A famous writer in late middle age, dependent on beta blockers and Viagra for his lows and highs, Juan Diego flies to the Philippines to fulfill a promise he made as a 14-year-old to an American hippie in Oaxaca. He stops taking the beta blockers, which interfere with his dreams. He sleeps deeply on the plane, “as if there were nothing that could wake Juan Diego from the dream of when his future started.”

On the plane, he meets two women, Miriam and her daughter, Dorothy, who are, as much as Irving would like to keep us guessing, clearly spirit guides from another world. Their behavior is too intimate, too controlling, and they do not appear in photographs. They may be from the clan of the Virgin, but they are not above fucking Juan Diego’s brains out. In this fugue journey, where sex and religion set the mood, Juan Diego tells us the story of his life.

In the days when the phrase “magical realism” meant something other than the surreal present tense, when it was an art form and not a way of coping, critics tucked John Irving and Gabriel Garcia Marquez in the same cozy paragraphs. Magical realism helped us hold the other at arm’s length. Those wacky Catholics with their rituals. Those miracles that lift up the poor. That dream sequence where we see the path not taken.

But now the present contains more menace, and the other—the poor, the racially, sexually, or religiously different—cannot be held at arm’s length. There simply isn’t enough room for arm’s length, what with information technology, resource scarcity, and population growth. We all live in an age of trauma; an age in which our brute will has failed us. In Avenue of Mysteries, trauma pushes Juan Diego (as it does with all of us if we are lucky) into a life lived in his imagination. Not so much magical realism as survival.

Anyway, Irving won’t let us hold these characters at arm’s length. He grips us in the web he has woven. If you struggle, if you disagree, if you raise lumpen questions that reveal your utter lack of intelligence, and worse, consciousness, you feel his wrath. Since Juan Diego is a famous writer, the book takes merciless swings at clingy readers who want too much from writers and focus on all the wrong details; students of literature whose analysis only reveals the hamster wheel their ego keeps them on; and really the whole English literature machine. Heaven help the critic. Bottom feeders. Only thing worse is a scientist.

But Juan Diego has also taught writing, though he “had not once told his students how they should write; he would never have suggested to his fiction-writing students that they should write a novel the way he wrote his. The dump reader wasn’t a proselytizer.” Neither is Irving.

So what is this all about? Why read a novel that conflates time and space and challenges the notions on which we build a reality that may not be magical, but heck, it’s home?

Perhaps because the novel is to writing what the black box is to theater. You step into it. Once inside, John Irving will tell us that there may be such a thing as fate. That books can bring back the dead. That time and space are barely understood constructs and it is possible to triumph over them. Unless you are one of the few that has made ignorant peace with the boundaries we assume, this is extremely comforting. No, it’s exciting.

The avenue of mysteries is a pilgrimage that Juan Diego and Lupe take with other pilgrims to throw their mother’s ashes on the giant statue of the Virgin Mary. (Lupe detests the giant Virgin Mary; she much prefers the more human-scaled Guadelupe Virgin.) There’s no denying that life is one big avenue of mysteries. But if Juan Diego could teach himself to read, and Lupe could read minds and see the past and the future, surely we too can teach ourselves to read the past and the future. Surely we can see collisions coming. And, like Lupe in her way and Juan Diego in his, triumph over them.