Quick! Stop what you are doing! Are you sitting down? Well, sit down and listen carefully, because I’m only going to say this once. In a few seconds I am going to ask you to get up and walk slowly to the door. You got that? Just drop what you are doing and walk out the building. No questions. Walk a block south. At the end of the street is a pay phone. It will be ringing. You’re going to pick it up and find me on the other end. I’m going to ask you some questions. Your answer to these questions will determine whether you live or die. Yes, you heard me right. Do not panic. Breathe deeply. Are you ready? OK, now get up. Turn around. Touch the ground. Say five Hail Marys and......... go.

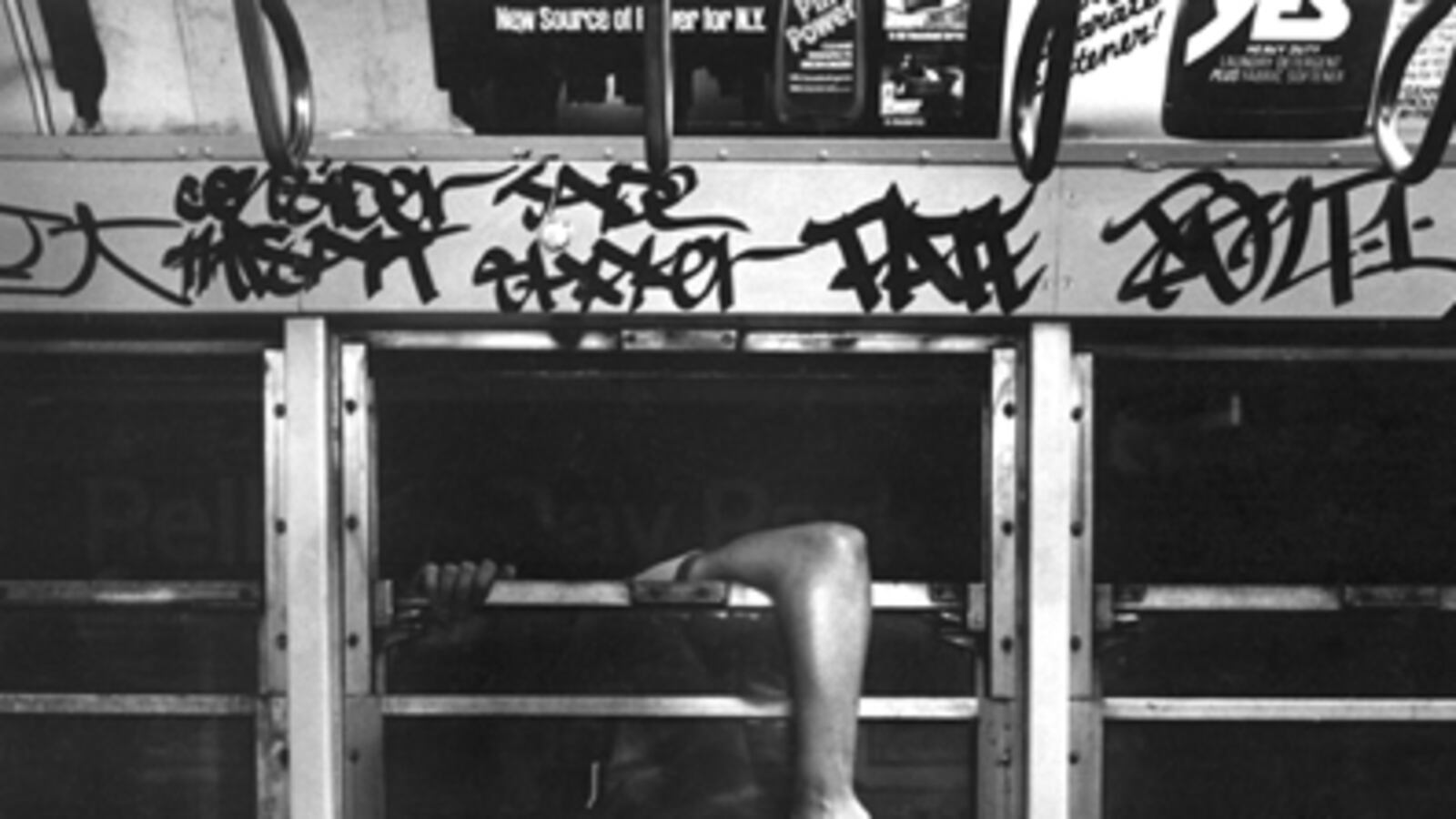

Click Image Below to View Nightmarish Photos of New York’s Subways in the 1980s

Why are movie villains such control freaks these days?

In The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, which opens this week, John Travolta plays Ryder, a psycho who holds a subway train hostage and threatens to shoot one passenger every minute unless MTA subway dispatcher Gerber (Denzel Washington) can deliver $10 million in unmarked bills to him. He’ll also kill a passenger if Gerber passes the phone to anyone else. Or gets someone else to deliver the money. Or if he refuses to tell the truth about his personal life. “I’m not a hostage negotiator,” protests Gerber. “I’m just a civil service employee.” No matter. Ryder is not your average villain. He’s that very modern type: the omniscient sicko, the all-controlling puppeteer who uses his vast knowledge and power to manipulate others into jumping through a series of ever more difficult hoops. Frequently, he calls out of the blue, using the public pay phone system to pose a series of bizarre riddles which end with a mad race across town in rush-hour traffic. Cultural critics are in disagreement over the precise roots of this phenomenon—the plunging Dow, the rising tide of alienation and anomie in today’s cities—but they all can agree that it allows audiences a good working knowledge of what it is like to go to lunch with Ari Emanuel.

Sounds like a variant on your typical lone wolf nut job to me.

No. In the original, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, the villain was played by a superbly nonchalant Robert Shaw, coolly flicking through the pages of a puzzle book as he bargains with people’s lives. Travolta, despite a badass neck tattoo and a Fu Manchu beard, is a needier, more attention-hungry presence, glomming onto Denzel Washington within seconds, and peppering him with personal questions in slightly co-dependent fashion. “Is this the bit where you reach out to me?” he asks. “You thought you would come down here and redeem yourself?” He is all-knowing in the manner of modern movie villains, which is to say he seems to have watched a ton of movies. “I knew exactly how this day was going to start,” he says.

The all-controlling omniscient-sicko is less a character in the drama, in fact, than the eyes and ears of the dramatist himself, a kind of internal excitement czar, making sure that everything goes according to plan—an explosion here, a car chase there.

So when did all this begin?

Film historians are divided as to the exact beginnings of the OCD villain trend, but many point to 1993, when Speed screenwriter Graham Yost discovered that the only thing he needed to get his bomb-on-a-bus plot going was a payphone and a quarter. “Pop quiz, hotshot,” barks Dennis Hopper. “There's a bomb on a bus. Once the bus goes 50 miles an hour, the bomb is armed. If it drops below 50, it blows up. What do you do? What do you do?” Voila! Why Hopper was doing all this is still a matter of some conjecture, although some audiences members claim fleeting memories of a plot having to do with a disgruntled cop..... a lost pension..... a burned arm..... maybe he was a fireman..... no, sorry, it’s gone. Others simply grooved on His Hopperness.

I liked Speed, actually.

Yes, but it was quickly followed by Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995) in which Bruce Willis was hounded across New York City by an effeminate European identifying himself only as Simon. Why must Willis walk through Harlem wearing a sandwich board bearing racial slurs? Because Simon says so. Why must he work out how to measure 3 liters of water from a 5-liter can? Because Simon says so. It turned out Simon was merely providing cover for a gold-bullion heist, although how this end was served by playing cat-and-mouse games with a cop was never explained. “We're dealing with a megalomaniacal personality with possible paranoid schizo...” explains a police psychologist, before Willis cuts him off. “ Hey, hey! How 'bout we just skip down to the part where you tell me what the fuck this has to do with me, huh?”

That’s a good question. What does it have to do with him?

Nothing. But given the hyperkinetic demands of the modern-day action movie, drastic measures are needed to weld hero and villain together. It also saves filmmakers the onerous task of linking the various bits of their plot. Instead, the villain does it for them. The all-controlling omniscient-sicko is less a character in the drama, in fact, than the eyes and ears of the dramatist himself, a kind of internal excitement czar, making sure that everything goes according to plan—an explosion here, a car chase there. Things reached a pitch of almost Pinteresque absurdity in last year’s Eagle Eye, in which Shia LaBeouf was shepherded through a vast and inexplicable plot by a silken-voiced cellphone caller— who was never unmasked. It made the most sense, in fact, to imagine the voice as belonging to LaBeouf’s director, D.J. Caruso, mega-phoning in his instructions for each scene: OK jump out the window! Now swing onto that crane! Watch out for that car! Hit that guy! Fire the gun! Run! Don’t look back! Fire! Duck! Run! Roll!

You sound pretty down on the whole thing.

I just wish villains would work out of their own narrow self-interest and not worry so much about the broader demands of the drama they happen to be in. It makes them look fussy rather than frightening. Travolta puts on quite a show but exudes a threat level of precisely zero.

Watch the Trailer of The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3

What happened to those questions you were going to ask me?

Oh. Right. Sorry.... As I was going to St. Ives, I met a man with seven wives. Each wife had seven sacks. Each sack had seven cats. Each cat had seven kits. Kits, cats, sacks, wives. How many were going to St. Ives?

This game is boring.

Exactly my point.

Tom Shone was film critic of the London Sunday Times from 1994-1999. He is the author of two books, Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer (Free Press) and In The Rooms (Hutchinson), his first novel, to be published July 7. He lives in New York.