Even at a time of bitter political partisanship and ideological division, celebrating the Fourth of July remains a surpassing national ritual of patriotic unity. The hot dogs and picnics and fireworks are the show; beneath them stirs a common veneration for the Declaration of Independence and especially its opening passages about the self-evident truths of equality and humankind’s inalienable rights. Americans spend the rest of the year either taking those words for granted or fighting intensely—and, these days, bitterly—over what the words mean in our own political time. But for one blessed solitary day, we give the arguments a rest in order to express gratitude, delight, and even wonder at what Thomas Jefferson and his colleagues wrought in 1776. And many people lament a fancied bygone time when this basic unity pervaded American political life all year long, despite our many differences.

Federalists vilified Jefferson as a snake in the grass, and denigrated his role in the writing the Declaration.

The nostalgia misreads not just American political history, which has generally been a chronicle of sharp conflicts, but the history of the Fourth of July as well. Independence Day now may bring a break from passionate argument. During the decades after the nation’s founding, though, the occasion prompted furious partisan declamations and fractious rhetoric.

The very first celebrations occurred on July 8, 1776, when bells rang and bonfires crackled throughout Philadelphia following the first public reading of the Declaration. A year later, the city settled on July 4th for its festivities, and that has been the date ever since. Yet for all of their enthusiasm for independence, Americans said little during the Revolution about the Declaration’s egalitarian political principles. It was enough simply to commemorate the Continental Congress’s decision to sever the colonies from Great Britain.

Independence Day became a much bigger deal—and a festival of polemic—during the 1790s. Led by Jefferson and James Madison, opposition to the policies of President Washington and his successor, John Adams, created the first rough approximations of American political parties. At the heart of the conflict were fundamentally different visions of what the American republic ought to become, and the frenzy was the worst in American history except for the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction. By decade’s end, pro-Administration Federalists enacted a Sedition Law to help suppress what they deemed the dangerous radicalism of Jefferson’s and Madison’s Republicans.

• T.H. Breen: The Secret Founding FathersPro-Jeffersonians seized upon Independence Day to celebrate the Declaration and its author, and to celebrate equality as well as independence. “’All Men,’ says this sublime instrument, are born ‘Free’ and ‘Equal,” one Boston Republican newspaper proclaimed, while affirming that these were “the first principles and the declared ends of our happy Revolution.” Conservative Federalists countered that Americans ought not to be overly taken in by what one July Fourth orator called “the seductive doctrines of ‘Liberty’ and ‘Equality’”—a claim one Republican editor swiftly denounced as obnoxious “petulancy and rant.” Some of Jefferson’s more conservative Anglophilic foes went even further; as late as the 1820s, the Massachusetts ultra-Federalist Timothy Pickering was maligning the Declaration’s rhetoric as excessive, a “high-wrought Philippic against Great Britain and her King.”

When they weren’t casting aspersions on democratic egalitarianism, Federalists vilified Jefferson as a snake in the grass, and denigrated his role in the writing the Declaration. (“The draft reported by the committee has been generally attributed to Mr. Jefferson,” was as much credit as Chief Justice John Marshall was willing to give.) Republicans, for their part, turned their Fourth of July speeches into glorifications of their hero as the man who “poured the soul of the continent into the monumental act of Independence.”

The Jeffersonian Republicans didn’t refrain from delivering their own Fourth of July denunciations of the Federalists (who commanded Congress and the courts as well as the presidency through almost all of the 1790s). Plainly thinking in part of the Sedition Act, one speaker in Mount Pleasant, New York, on July 4, 1799, observed that “when the servants of the people assume the airs of masters, when they are urgent in their claims for confidence … the people should displace such servants the first legal opportunity.” That same day, at a celebration in Kennebunk, Maine, a Federalist blasted the opposition as French-style radicals—“our licentious democrats”—and averred that “if we had no seditious Jacobins in this country, there would have been no necessity for the “Sedition Act.”

Jefferson’s elevation to the White House in 1801, along with a Republican-controlled Congress, spelled the beginning of the end of those early conflicts—and of the Federalist Party. By the 1830s, the Fourth had begun to become more non-partisan, until the sectional crisis over slavery shattered the nation itself. In a bid to reinforce the Union victory in the Civil War, Congress, in 1870, formally established Independence Day as a federal holiday; thereafter, the Fourth has evolved into the day of national unity is has been for a long time. The evolution has been all to the good. But it should not obscure how the Fourth of July began—or hoodwink us into believing that today’s partisan battles are somehow unseemly, or even un-American.

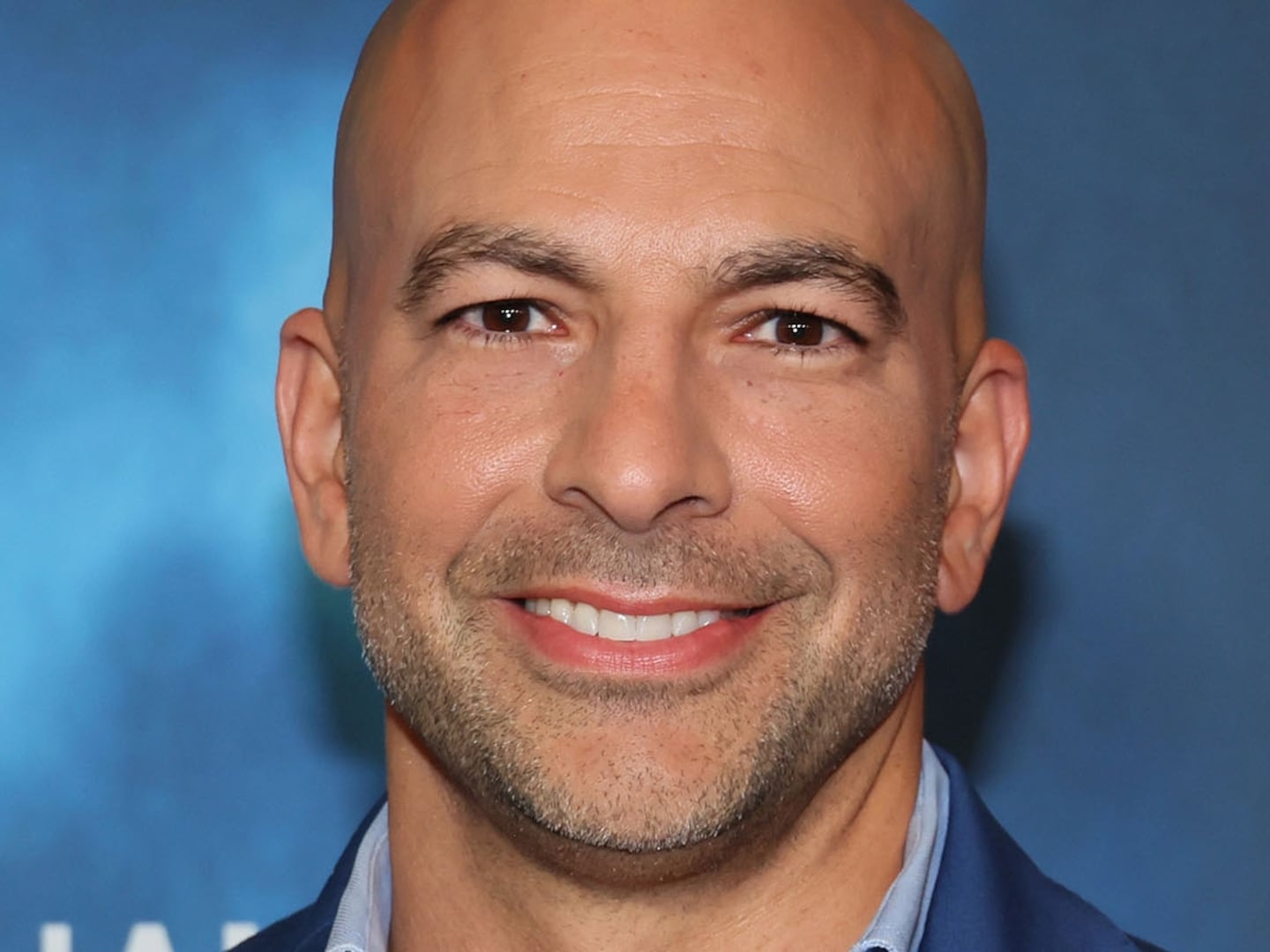

Sean Wilentz is a history professor at Princeton University whose books include The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln and The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974-2008.A contributing editor at The New Republic, his new book, Bob Dylan in America , will be published in September by Doubleday.