Laura at 11D is mystified by people who oppose assault weapons bans:

I try very hard to understand the far right, but the extreme gun people are beyond me.

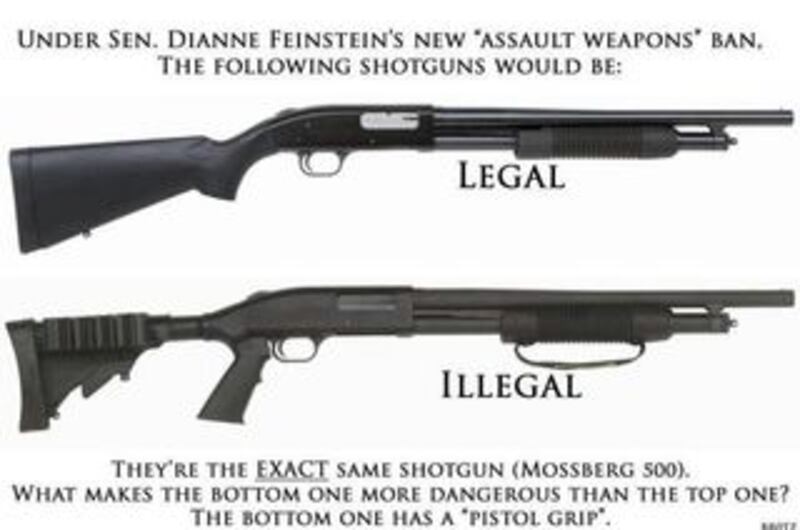

If you can buy the gun on the top, but can't buy the bottom gun, who cares? You still have a gun.

I'd turn that question around: if it makes no difference, then why have the law? There's little evidence that the assault weapons ban achieved its ostensible purpose of making America safer; we did not see the predicted spike in crime when it expired in 2004. That's not really surprising, because long guns aren't used in the majority of gun crimes, and "assault weapon" is a largely cosmetic rather than functional description; the guns that were taken off the street were not noticeably more lethal than the ones that remained. It was a largely symbolic law that made proponents of gun control feel good about "doing something".

But we should not have largely symbolic laws that require real and large regulatory interventions. There should always be a presumption in favor of economic liberty, as there is with other liberties; to justify curtailing them, we need a benefit more tangible than warm and fuzzy feelings in the hearts of American liberals. But that is not the only reason that we should oppose ineffective, or marginally effective, regulations. There's also an important question of government and social capacity.

Every regulation you pass has a substantial non-monetary cost. Implementing it and overseeing that implementation absorbs some of the attention of legislators and agency heads, a finite resource. It also increases the complexity of the regulatory code, and as the complexity increases, so does uncertainty. A few months ago, I talked to a former business owner, as solid a liberal as you could ever hope to meet, who said that one of the reasons he gave up was that it was simply not possible to know whether he was in compliance with various tax and employment regulations; the best he could do was hire experts. But if Paychex took an extra $100 per employee out of his account, he basically had to trust him; there was no way for him to get sufficiently familiar with all the relevant rules to check their work.

A related problem is that these regulations not-infrequently conflict, so that every time you pass a rule, you increase the risk that compliance is not merely unknowable, but actually impossible.

You also require congressmen to become experts in more and more subjects--with the result that they're shockingly ignorant about the stuff they vote on. This is no slam on congressmen, who for all my criticisms, work amazingly hard. But there is no way that anyone could be even remotely qualified to have opinions on all the matters where they are expected to shape US policy. They're spread far too thin--and the result is that when I hear them talk, I am frequently somewhat amazed at the gaps in their knowledge of the areas I cover--areas where they are actively engaged in passing major bills. I'm not talking about the standard misleading talking points of their party; that's is an occupational requirement for which I have to cut them some slack. I'm talking about saying things which show that they clearly don't grasp the basic theory of, say, how credit card interchanges or macroeconomic policy work.

That's not an argument for regulations that may do a lot of good--preventing people from dumping toxic chemicals into the rivers, or defrauding customers, are legitimate and necessary exercises of government power. But it is an argument for carefully considering those non-monetary costs, and trying to trim the overall regulatory burden to reduce that complexity wherever possible.

A law that has no obvious benefit, but substantial regulatory cost, just obviously flunks this basic cost-benefit analysis. It's also an intrusion on the liberty of American citizens. You don't have to be a gun nut to get mad about that.