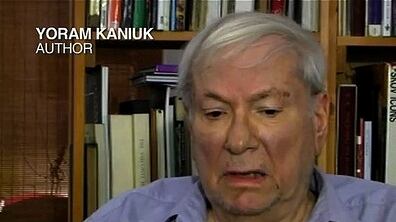

He died on my birthday, this past weekend, a person exactly twice my age, one of the many Jews who lived out their days doing battle with their identities as citizens of Israel. Ravaged by cancer, celebrated Israeli author Yoram Kaniuk challenged convention until his final days, taking a parting shot at the religion that he never renounced, but which he challenged in the context of Jewish sovereignty.

The author of 17 novels and seven short story collections, and the winner of Sapir Prize for Literature for his memoir 1948, an account of his experiences fighting in the War of Independence, Kaniuk was additionally thrust into public consciousness for defying convention regarding Israeli Jewish identity. In 2011, he successfully demanded that the Interior Ministry officially change his status to “no religion.” Evidently he was motivated by the fact that his wife (and thus children and grandchild) are not Jewish, and his distaste for the idea of living in what he termed a “Jewish Iran.”

As he was dying, he shared his final wish: no burial, as Jewish tradition would dictate. Instead, he would donate his body to science, before being cremated.

At the time of his 2011 protest, Gershom Gorenberg pointed to an irony in Kaniuk’s move to be declared “no religion,” namely that Kaniuk was “implicitly...affirm[ing] the clerical establishment's claim to represent Judaism.” “Real freedom of conscience,” Gorenberg suggested, “would require the state to stop registering religious and ethnic identity.”

Two years after Kaniuk’s move, religion and state in Israel are very slowly being pried apart as religious pluralism is gradually coming into view.

Still, what does it mean, amidst a legacy of pushing the Israeli state to express its mission in national, rather than in religious, terms, to abandon Jewish tradition in one’s final moments?

All death rites have their own integral logic, their own sacred integrity, of course. But one needs only to stand at a Jewish burial, shoveling dirt to displace the air that remains around the deceased, holding up the mourners as they recite kaddish, “the one about the world that will be made new,” as Leon Wieseltier described it, and gazing outward to the Kohanim—the contemporary vestiges of the ancient priestly class who stand patiently at the edge of the cemetery—to realize how complex a statement is Kaniuk’s decision to forgo this final expression of Jewish ritual.

As much as the Jewish state has shaped the experiencing of Jewish life according to the rhythms of the Jewish calendar, and enabled its artists, authors, poets, and songwriters to flourish under the arc of a resurrected Hebrew language, there is a clear and present tension between modern, Jewish, democratic sovereignty and the nuances of Jewish identity. To be sure, many Israelis are separately and together continuing to negotiate these questions.

As Kaniuk has left us, the demands he has made of his state echo on, quietly framing the Aramaic of the kaddish that his loved ones may or may not be reciting for him.