Somebody from Norton should pass out copies of Nicholas Wapshott’s Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics at Occupy Wall Street and other similarly occupied financial hubs. It will, at the very least, help the protesters frame the debate, which is really about the relative merits of economic intervention or of sucking up the economic pain and letting the system heal itself.

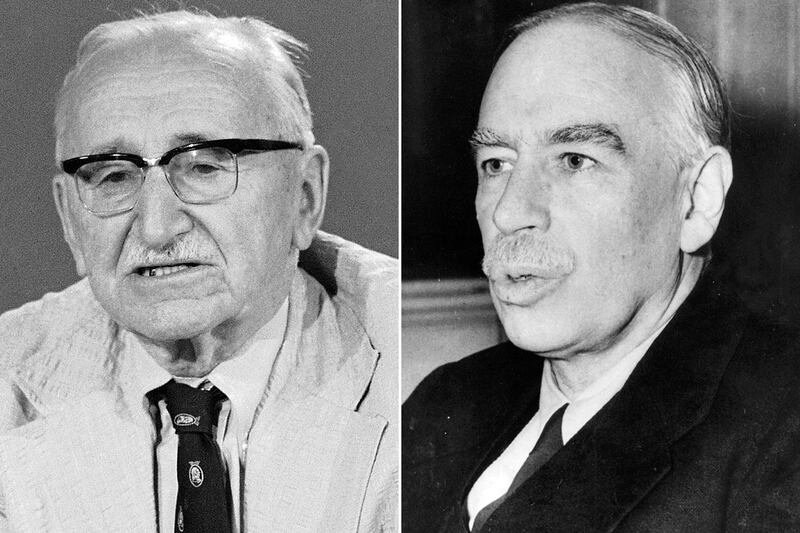

On one side stands John Maynard Keynes, the English economist and proponent of interventionism who believed that high unemployment in Britain left capitalism vulnerable to “attacks and criticisms of Socialist and Communist innovators.” Keynes, by the way, was no Socialist, even if some describe him that way now.

On the other side is Friedrich von Hayek, who lived through the ruin of Vienna as its government printed money to pay its war debts and reparations after the First World War. Hyperinflation was so bad that it cost a billion marks to buy a glass of beer. For Keynes, inaction in the face of economic pain is a sin. Markets do not right themselves without help. For Hayek, the schemes of fallible human beings are more likely to end in disaster than to solve any problems. Markets eventually find equilibrium, unless they are interfered with.

Most of us are on the outside of the debate. We have no voice in economic policy but must live with the outcomes of the decisions made for us. Both Hayek and Keynes lived through periods of war and social unrest. Neither would be surprised to witness violent anti-austerity protests in Athens and Rome, or more peaceful acts of civil disobedience in U.S. cities.

The fundamental difference between the two is that Keynes is something of a tinkerer. He basically invented macroeconomics as it is practiced today in the monetary policies of the U.S. Federal Reserve, where interest rates and the money supply are used to heat up or cool down the economy. Wapshott gives us no less than Milton Friedman, the father of monetarism, claiming himself something of an heir to Keynes.

Hayek was a self-described Libertarian Utopian, who near the end of his life believed that government interference with the money supply is the cause of any recession or depression the world has ever endured. Hayek’s gift to Occupy Wall Street would be his parable The Road to Serfdom, a warning about people who give up their economic freedoms in exchange for material comforts and soon find they have given away the rest of their freedoms in the bargain. Hayek believed that even democracy could be unfair because the majority might abuse the minority, and that a functioning market is the only reliable form of democracy on earth.

Though many current Tea Party members were undoubtedly familiar with Hayek, Wapshott credits political commentator Glenn Beck with helping to repopularize The Road to Serfdom by pushing it on his now-defunct television show, and to rekindle an appreciation for Hayek among the political right more generally. But readers should be wary of drawing too many political conclusions based on associations with either Hayek or Keynes. Judging by their policies, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Ben Bernanke have to be classified as Keynesian. But British Prime Minister David Cameron, currently pursuing a harsh economic-austerity agenda, is certainly not libertarian enough to claim Hayek’s mantle. Ron Paul might fit the Hayekian bill, but that’s because Paul is too libertarian even for the Tea Party.

Wapshott, a columnist for Reuters and a former editor of The Times of London, presents these opposing views at their strongest. Though Keynesianism is now so embedded in economic policy that it would be difficult not to say he has carried the day, Hayek maintains his influence, according to Wapshott. When faced with a potential run on the pound sterling, Cameron embarked on a program of Hayekian austerity, even in the face of high unemployment and public anger over the government’s pulling back.

Were Keynes to visit Occupy Wall Street, he would no doubt be reassured of his belief that the government has a moral imperative to provide meaningful employment for its citizens. But he would have a hard time selling a large government-spending plan to a country that already borrowed for one stimulus and had its credit rating slashed in August.

Add to that economic reality an impending election being contested by two parties that have no intention of helping the other, and it seems that we will be testing Hayek’s theories until at least 2013. If Hayek is right, perhaps the markets will begin to find some natural equilibrium, and unemployment in the U.S. and Europe will drop with a return to growth. But the Hayekian world demands patience and resilience. It could take the markets longer than most would like (or, to paraphrase Keynes, markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent).

If Keynes is right, then inaction will lead to continued stagnation. But sooner or later, somebody will do something about it. As we’ve seen, both liberals and conservatives alike can be Keynesian, if the situation gets bad enough.