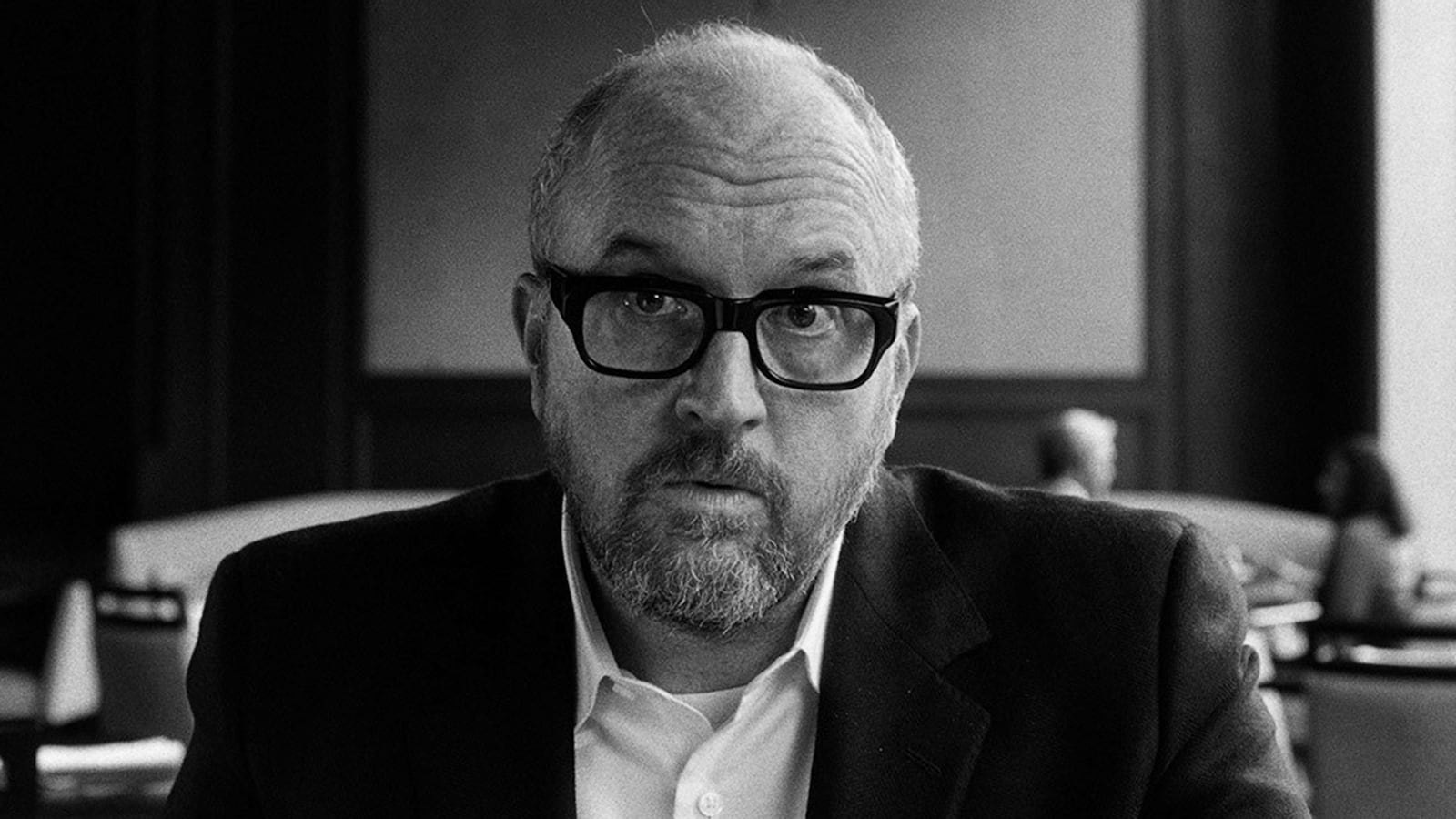

Like many contemporary comedians—Larry David and Ricky Gervais come easily to mind—Louis C.K. is a television star known for making a career of placing himself in embarrassing, often cringe-inducing scenarios.

In recent weeks, C.K. has had cause to be legitimately embarrassed about matters outside the realm of fiction, since various accusations about his supposed sexual misconduct, which have been floating around for years since a 2012 Gawker story outlined the rumors, have resurfaced. Claims that C.K. coerced various women, including fellow comedians, to watch him masturbate are the talk of the blogosphere, despite the fact that the man hailed by many as the one of the most inventive entertainers of his generation has neither confirmed nor denied these allegations. Tig Notaro, whose One Mississippi lists C.K. as an executive producer, has been especially vocal, telling The Daily Beast’s Matt Wilstein that if the accusations are true, the comedian’s inappropriate bouts of self-pleasuring are not merely eccentric but constitute acts of bona fide sexual assault.

Given this mini-scandal, C.K.’s I Love You, Daddy (which premiered on Saturday at the Toronto International Film Festival) resembles a farcical hall of mirrors. The star of Louie and Horace and Pete plays Glen Topher, a television comedy writer whose lame sitcom on nurses seems to be going nowhere until he snags the beautiful Grace Cullen (Rose Byrne) for the series’ lead. In the meantime, Glen’s nubile 17-year-old daughter, China (Chloe Grace Moretz), becomes enamored of Leslie Goodwin, a sixtysomething director (played with sly hauteur by John Malkovich, more often than not donning a foppish ascot), a shameless seducer with a Woody Allen-ish weakness for young girls but a demeanor more reminiscent of the cynical roués from ’40s movies that were often played by George Sanders.

C.K.’s Glen is essentially a new incarnation of the frequently politically incorrect, if essentially ethical, character that he played in bite-size installments on Louie. The more ambitious scope of I Love You, Daddy (which begins to drag near the end of its two-hour running time and increasingly resembles an overlong sitcom episode) allows for the schlemiel-like protagonist to engage in more elaborate exercises in merciless, intermittently funny self-flagellation.

As was true of C.K.’s television work, the film’s comic trajectory enables the characters to undercut their own bad behavior with spasms of liberal guilt, however hypocritical in nature. This ploy is especially apparent in the confrontations between China and Goodwin, the priapic director constantly fending off accusations of pedophilia. Nothing if not sexually strategic, the cagey Goodwin appeals to the naïve—but intellectually curious—China by slyly asking her if she’s an “intersectional” or “radical” feminist. Once China learns the definition of these terms and becomes convinced that she needs to combat “the patriarchy,” she proclaims: “Men have fucked us for so long that it’s time to fight back.” Goodwin’s banter with his paramour seems to affirm the common assumption that so-called male feminists are often the most irredeemably sexist men of all. In a similar vein, when Glen becomes enmeshed in an affair with the lissome Grace, he readily admits to being guilty of “mansplaining,” a ruse no doubt designed to please his fickle leading lady-to-be.

While Glen dutifully plays the role of concerned, angst-ridden father, his friend and sidekick Ralph (Charlie Day) is unabashedly vulgar to the point of being almost unhinged; he functions as both a bawdy Greek chorus and the id to Glen’s superego. He gleefully mimes jerking off at two points in the film and it’s hard to say whether his hand gestures can be deemed C.K.’s covert critique of his alleged misbehavior or a massive “fuck you” to his critics. Despite its longueurs, the most intriguing aspect of I Love You, Daddy is the film’s ambivalent view of its main characters. It’s difficult to determine if Leslie Goodwin is unforgivably sleazy or merely a pretentious twit who has been unjustly accused of child molestation. Similarly, some audience members may damn Glen as a neglectful father who fails to save his daughter from the clutches of a potential perv, while other spectators may view his failings as human, all too human.

It might almost be too cynical to assume that C.K. shares the assumptions of China’s best friend Zasha (Ebonee Noel), an uninhibited young woman convinced that “everyone’s a pervert.” For Louis C.K.’s detractors, this line might represent a clumsy effort to rationalize his real-life transgressions. For his many fans and defenders, Zasha’s interjection might comprise a salutary reply to the rampant gossip and moralizing that is currently making the writer-comedian a pariah in some circles.