“In an old house in Paris that was covered with vines lived twelve little girls in two straight lines…”

But it was in an old bar, Pete’s Tavern, near Gramercy Park in New York City, that Madeline, Miss Clavel, and the rest of the French schoolgirls in the phenomenally popular Madeline series of books were born from Ludwig Bemelmans’ mind.

Madeline was an adventurous little girl, growing up in a strict Catholic nun-run school, doing her own thing, getting into trouble. Mischievous and spirited, she was a heroine for generations of young girls who read and idolized her.

Bemelmans, who was raised in Austria-Hungary, first arrived in the United States in 1914 after having both school and behavior difficulties at home; he was offered the choice between reform school and America, and chose to head abroad; “I am part of New York, as so many foreigners are, and I love this city,” he later said of his decision.

Now, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Madeline’s emergence on the literary scene, as well as the centenary year of her creator’s arrival in the USA, the New-York Historical Society is hosting an exhibition, featuring more than 90 original artworks, Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans.

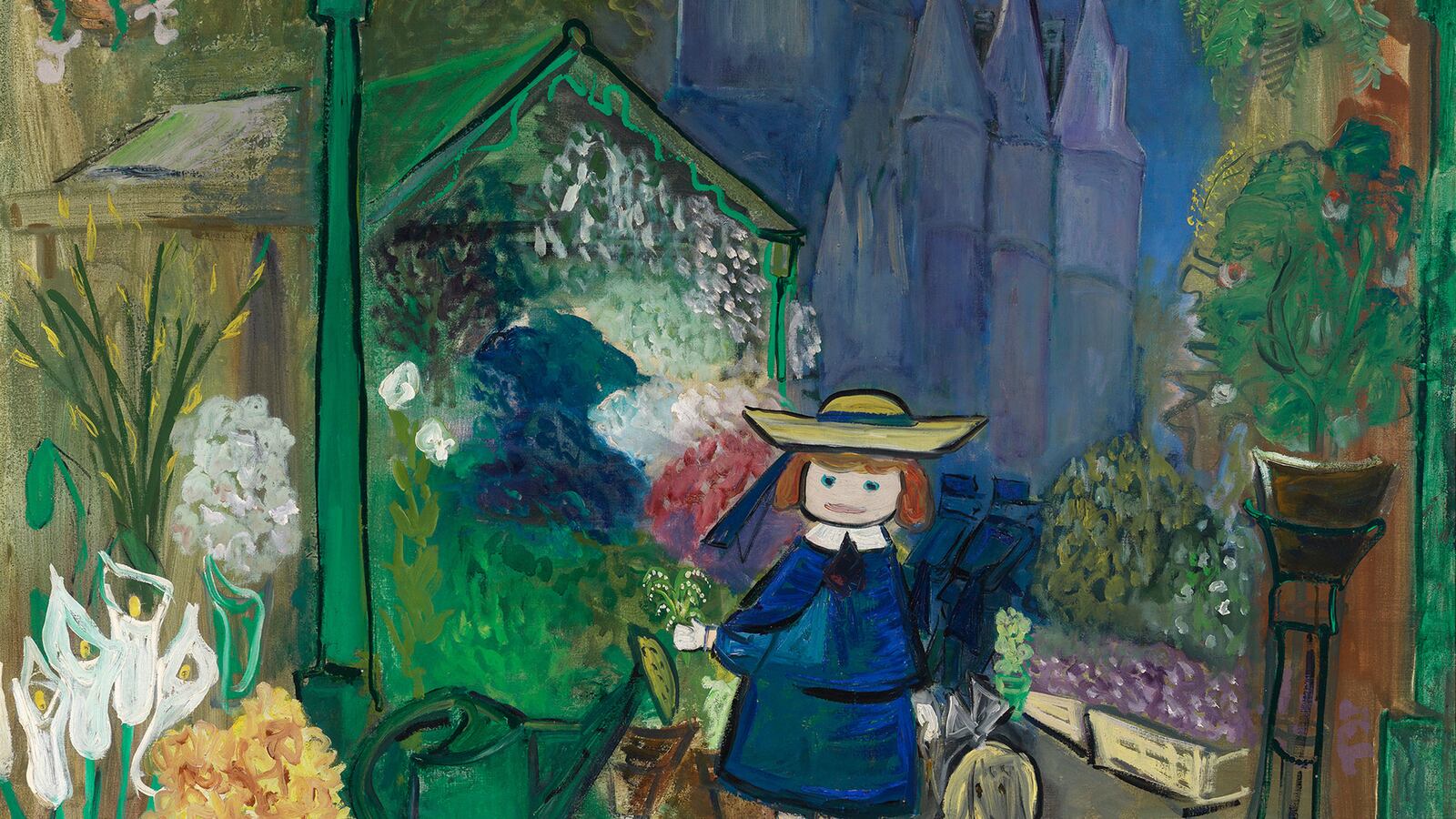

The exhibition includes drawings from all six Madeline books, alongside drawings of the old Ritz Hotel, murals from a rediscovered Paris bistro, and panels from Aristotle Onassis’ yacht, the Christina (named after his daughter), inspired by Madeline that Bemelmans painted in 1953.

Bemelmans, who spent his early years in the city working at luxury hotels—first the Astor, then the Ritz-Carlton, where he ended up spending 15 years—became fascinated with cartooning. He experimented with different characters and drawings. His Madeline, with her cheeky catchphrases and a Paris that, at the time, only existed in a dream (or Bemelmans’ book), was first published in Life magazine in September 1939.

GALLERY: Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans (PHOTOS)

The simple “vine” rhyme that surrounded the Catholic school girls, and their miniature, albeit confident and charismatic “leader,” was a cultural stepping stone for not just children’s literature, but for art as well. “The purpose of art,” Bemelmans once said, “is to console and amuse—myself, and, I hope, others.”

According to the retrospective, the idea of a pint-sized French schoolgirl heroine was derived from stories Bemelmans’ mother told of her life growing up in the Altötting convent in Bavaria. “I visited this convent with her and saw the little beds in straight rows, and the long table with washbasins at which the girls had brushed their teeth,” he said. “I myself, as a small boy, had been sent to a boarding school in Rothenburg. We walked through the ancient town in two straight lines. I was the smallest one.”

Madeline, in ways, was Bemelmans’ “alter ego and legacy.” A self-described “perpetual wanderer,” Madeline and her adventures were not just a product of his creativity, but an outlet he referred to as “therapy in the dark hours.”

Madeline too, had her share of wanders—she rescued a drowning dog in 1953, visited the circus with her friend Pepito, the Spanish ambassador’s son, in 1959, and in 1961, visited London. All the while, of course, in her royal-blue collared dress and coordinating yellow-ribboned hat (Bemelmans’ himself was a fan of millinery).

At the press preview for the exhibition, the Historical Society’s president and CEO, Louise Mirrer, joked that Madeline “secretly… was a New York kid.” Sure, the old house in vines may have been in Paris, but the spunk and curiosity of the 7-year-old redhead could certainly have also been found on Irving Place, the very place she was dreamt up in Pete’s Tavern by her creator.

Later she would also be found on the Upper East Side, where Bemelmans decorated the Carlyle hotel’s walls and lampshades with his illustrations. TV and film adaptations followed; and so to today, on Central Park West, where Madeline’s legacy, as well as Bemelmans’, is being both honored and celebrated.

The exhibition is at the New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, until October 19.