Desks are still being rolled into a half-empty suite in a bleak office park in suburban Des Moines, where Sondra Ziegler, her three young children in tow, has just shown up to volunteer for Newt Gingrich.

“I wouldn’t say Newt was my guy from the beginning,” says the 39-year-old home-schooling mom, who drove 14 hours from Lubbock, Texas, to help out. “It was through watching the debates. I heard they needed boots on the ground.”

That is an understatement, as the forlorn nature of Gingrich’s only field office in the state makes clear. The legend of the Iowa caucuses is that they require a candidate to practically establish residency in the state, meet voters in their living rooms several times—once is not nearly enough—and build a ground machine that will entice people to brave the winter cold for three-hour community meetings.

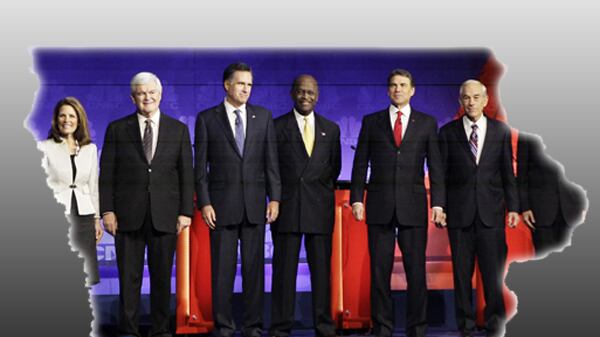

But this year is different as the once-broke Gingrich has rocketed to the top of the Iowa polls, with with a New York Times poll showing him the overwhelming choice. Mitt Romney, too, has barely set foot in the state. The county commissioners and power brokers who are accustomed to having their ring kissed suddenly matter far less than Fox News bookers. Iowa is now the first outpost of what has essentially become a televised demolition derby.

Mike Huckabee, who won the GOP caucuses in 2008, insists that candidates can’t beam their way to victory. “You cannot win Iowa without working it,” says the former Arkansas governor. “People want to see you, talk to you. If you don’t spend time, they won’t believe you’re serious about them.”

The caucuses have always had a crazy-quilt quality. “No rational person would design this system,” says Drake University professor Dennis Goldford.

Rational or not, the Jan. 3 voting means as few as 118,000 Republicans (the turnout last time) may well decide who claims the party’s presidential nomination. That, at least, is the myth that has surrounded Iowa ever since a peanut farmer named Jimmy Carter finished behind “Uncommitted” in 1976 and went on to win the White House. But in an era of online ads and endless cable debates, does working Iowa’s towns still matter?

“That not one candidate has a 99-chair organization just blows my mind,” says Tim Albrecht, a top aide to Iowa’s governor. “It’s pretty unheard of.” The candidates are zipping into Des Moines for Saturday’s ABC News debate, but most will zip right out again. One exception is Rick Perry, who is generating zero buzz here. He is launching a two-week Iowa bus trip to try to get back on the radar screen.

Romney, who has the remnants of his 2008 organization here, plans to spend a bit more time in Iowa but is wary of mounting a major blitz, while Gingrich, for his part, is also targeting South Carolina and Florida.

Such phone-it-in efforts undermine the central rationale for Iowa’s first-in-the-nation ritual: the slog of retail campaigning. “That’s been the calling card of the caucuses—we’re not star-struck by a governor or senator or CEO,” says state GOP chairman Matthew Strong. “We start the vetting here.”

But there has been precious little vetting in places like Cedar Rapids and Sioux City this time around. “We’ve reached out in a different way, through social networking and Twitter,” says a top Gingrich deputy, former congressman Robert Walker, who believes that “viral connectivity will play a role in Iowa”—which, he admits, is vastly cheaper.

A senior Romney adviser, trying to gloss over the candidate making just a half-dozen trips to a state famous for tripping up frontrunners, points to cable television. “We have engaged in Iowa through the debates,” the adviser says in an obvious stretch. “There’s been a national primary.”

As Republican Gov. Terry Branstad sees it, Romney has blundered and might not even finish in the top three. “He needs to spend more time in the state of Iowa to convince Iowans he really cares. He’s playing catch-up,” Branstad tells me in his ornate office in the golden-domed Capitol. At the same time, the governor adds, “last time he spent too much time, too much money and raised expectations. You’re from Massachusetts, your chances of winning Iowa are not great.”

But Gingrich hasn’t campaigned much here either, while those who have camped out in Iowa, such as Rick Santorum and Michele Bachmann, are stuck in single-digit status. “You’ve got to spend time there, but you also have to have something to sell,” says longtime Iowa columnist David Yepsen. Adds conservative radio host Steve Deace: “It’s almost as if the less time people get to see you, the better off you are. This is the familiarity-breeds-contempt primary.”

And then there’s the value of the prize itself, given the checkered history of the caucuses. “It’s a media event,” says Goldford. “It’s more important in suggesting who the winner is not going to be.”

Huckabee, a former Baptist minister, won by attracting a surge of evangelical voters, but his underfunded campaign soon sputtered. Branstad recalls begging Ronald Reagan’s team to do more than hold a few rallies in the state in 1980, when George H.W. Bush outcampaigned him and won Iowa (only to watch his self-proclaimed “Big Mo” dissipate soon afterward). As vice president, Bush flopped in Iowa in 1988, but recovered and captured the presidency. John McCain gambled in 2000 by blowing off the caucuses, winning big in New Hampshire before getting pummeled by George W. Bush.

Still, journalists love to hype the results before obsessing over New Hampshire a week later. Never mind that Iowa is a largely rural expanse of cornfields and hog farms that is 96 percent white, stunningly unrepresentative of the rest of the country. Never mind that the strong evangelical turnout gives outsize prominence to such matters as same-sex marriage, legalized by the courts here (though Republican leaders say these issues have been muted by the ailing economy). The state remains a field of dreams for lesser-known politicians hoping to break through.

The one candidate who is getting traction by working the state hard is Ron Paul, who has risen to second place in some polls. Before an overflow crowd in the tiny town of Boone on Thursday, the slightly built congressman recited his libertarian litany to frequent applause: Abolish the income tax, abolish the Federal Reserve, get out of the U.N., get the government out of spending even on such noble causes as cancer research. The message seemed to resonate among audience members who resent the nation’s capital. “Our government is so self-serving,” declared a man in a black jacket, complaining that “the lowest unemployment is in Washington, D.C.” Another asked Paul: “How can we win without the media recognizing you?”

The candidate responded that “it will be tough for them to ignore” if he scores big on caucus night.

But even if Paul or Bachmann manage to win the state, odds are they are one-state wonders who will fade soon afterward. If Gingrich caps his improbable comeback by taking the caucuses, he would get a huge boost that would leave Romney desperate to win the following week in New Hampshire, where he has a vacation home, or risk an early collapse.

Bob Vander Plaats, who ran Huckabee’s Iowa campaign and is now president of Family Leader, which fights for “God’s truth,” says “someone should have told Romney that ‘if you win Iowa, no one’s going to stop you.’ That’s just not being very bright.”

In the end, the Iowa contest will turn on the oldest ruse in politics: the expectations game. Of course Newt will win, Romney advisers say privately. He’s surging like crazy. He has to win. We haven’t made a serious effort. That’s largely true; Mitt’s spent a fraction of the $10 million he dumped on the state last time. Why? Because doing more, they say, would have ratcheted up expectations that he might win, making a loss all the more devastating.

And how has the former House speaker attained this commanding position, despite the accumulated wisdom that a winning candidate needs a small army of volunteers? The same way Herman Cain led the Iowa polls before his campaign imploded: Gingrich has appeared on Fox News, his former employer, more than 50 times (with one poll showing him the overwhelming choice of those who get most of their information from Fox). That route to victory—which doesn’t run through Des Moines—may soon relegate the caucuses to sideshow status.

What would be lost if Iowa, or New Hampshire, becomes irrelevant? “A candidate needs to hear from an unemployed truck driver, a farmer who had to sell off 10,000 acres of land to pay his bills,” says Huckabee. “You don’t get that by going to midtown Manhattan for a $35,000-a-plate fundraiser.”