The historic economic downturn resulting from the coronavirus has presented corporate America and allied lawmakers in Washington, D.C., with a once-in-a-generation opportunity to relax legal protections around the workplace. And, as of now, they appear poised to make a serious run at it.

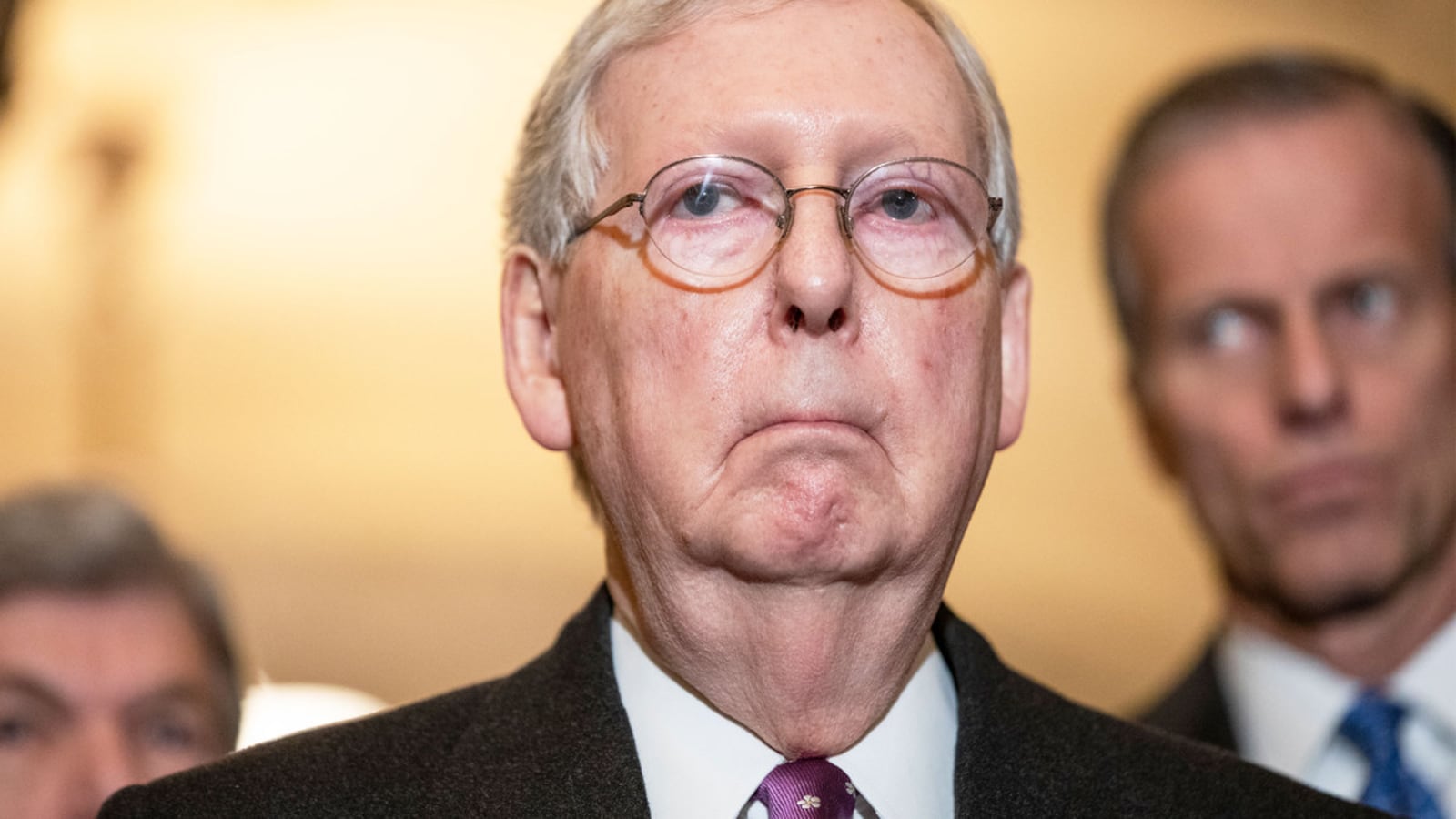

Over the past few days, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and key figures in the Trump White House have begun beating the drum to soften or outright end legal liabilities for employers who bring back their work forces amid the coronavirus pandemic.

The push has been aided by a number of corporate entities which have begun lobbying behind the scenes to minimize or avoid the threat of lawsuits from consumers or workers during attempts to re-open the U.S. economy. And those lobbyists aren’t shy about their ambitions; they want to use cases where there is broad consensus for limiting the legal exposure of companies or institutions and build a movement far beyond there.

The hope, said one GOP lobbyist working on the matter, is to get “a foot in the door” by having liabilities waived for hospitals and medical supply manufacturers, and to “splinter the Democrats” on the other cases. “That's what we are trying to put together.”

The success of this effort could have impacts beyond just individual industries and workplaces. As Congress reconvenes, Republicans and Democrats are heading for an irreconcilable impasse over whether the next major COVID relief bill should include provisions requiring a revamp of legal liability laws.

Democrats insist that any further coronavirus relief must include additional relief funds for state and local governments hard-hit by the COVID crisis—as much as $1 trillion, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) said on Thursday. McConnell has backed off his previous call to allow some states to go bankrupt, if need be. But he has done so while adding his insistence that any new measure must limit employer liability.

“I think any additional assistance that we provide for state and local government also needs to include some things [for] the brave businesses that will be reopening concerned about an epidemic of lawsuits that will be brought by the plaintiff all over America in the wake of this pandemic,” McConnell said on Thursday. “We don't need an epidemic of lawsuits in the wake of the pandemic.”

On this front, McConnell has an ally in President Donald Trump, who has for weeks personally pushed for this type of liability shielding for the reopening of small businesses in the face of the global pandemic. Trump has been extremely sensitive to the topic of lawsuits against corporate entities and business figures (such as himself), complaining that it’s been too easy for regulatory bodies or individuals to hassle companies, especially his own, with what he deems frivolous legal action, a source close to Trump told The Daily Beast.

Early last week, the president stressed at a press briefing that he and his administration “have tried to take liability away from these companies… We just don’t want that because we want the companies to open and to open strong.” He added that a “legal opinion” would be out soon. It’s unclear what that opinion is or when it is coming.

“It’s something the White House National Economic Council is studying and looking at seriously to protect American workers and businesses,” said a White House official.

For congressional Democrats, the push to expand legal liability is so far being treated as a bit of a head fake. McConnell only began aggressively discussing this idea when his initial campaign for forcing states through bankruptcy was roundly criticized.

“I think he had to back off his hard line on that and found the one thing that unifies Republicans,” said one senior Democratic Senate aide. “The fact of the matter is they’re not proposing anything specific except saying we need a liability shield.”

What’s more, it’s unclear what authority the extent of authorities the federal government really has in this domain. Currently, liability laws for employers vary widely from state to state. In states like New York, a plaintiff must prove that an employer deliberately sought to harm an employee for any damage payouts to be considered. In North Carolina, an employer can be civilly liable if they engage in conduct “knowing it is substantially certain to cause serious injury or death to employees.”

Should McConnell follow through on demanding an end to legal liability laws, it will likely encounter heavy opposition.

“We’re not going to negotiate from the position of saying, we’ll take a few crumbs, a few dollars, for local communities and in return you’re going to have to give up all kinds of legal protection for workers,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), a vocal proponent of organized labor, on a press call Thursday. “That’s been the McConnell way—always put it on the backs of workers—and we’re simply not gonna bite.”

Already, there has been some movement towards relaxing legal exposures for those states and industries at the front lines in fighting the coronavirus. Washington state recently announced that in “most cases,” if a worker contracts COVID-19, it is not a “work-related condition” that is eligible for compensation under current law. Manufacturers of N95 masks were granted legal liability waivers for products related to combating coronavirus as Congress leaned on them to ramp up production in the early weeks of the disease’s spread in the U.S.

Additionally, the Securities and Exchange Commission recently approved a request from Amazon to scuttle a shareholder vote that would have compelled the e-commerce giant—under scrutiny for labor conditions at its warehouses amid COVID—to develop and release a plan to ensure workplace safety. More recently, President Trump signed an executive order requiring meat packing plants to continue operations that included liability protections for the companies.

A behind-the-scenes flurry of lobbying activity in the first iterations of COVID-19 relief suggests that the movement to loosen liability laws won’t end there.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the country’s leading lobby for businesses, has been the most visible proponent of liability changes so far. According to federal filings, the Chamber spent millions lobbying on several bills, including the CARES Act, for “provision relating to liability issues.”

On April 13, the Chamber released a so-called “Return to Work” plan outlining a plan to ease the country out of the COVID-incuded economic lockdown. The lobby recommended limiting employer liability, noting that exposure to lawsuits was “the largest area of concern for the overall business community.”

“If enough claims are brought,” the Chamber warned, “the scope and magnitude of the litigation still may exert enough pressure to threaten businesses or industries with bankruptcy.”

The Chamber, an umbrella group with thousands of member companies and entities, has been doing the lion’s share of lobbying on this front. But others have pressed their case to lawmakers; the National Grocers’ Association, which represents 20,000 smaller grocery stores nationwide, lobbied Congress for “liability protection” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Uber, meanwhile, spent $80,000 lobbying Congress on “proposals to provide protection from future employment classification liability challenges,” according to its federal filing. The issue is a longstanding concern for Uber, which has fought hard to treat its drivers as independent contractors, not employees. so as to limit their legal responsibility for them.

It’s not only the pro-business and medical industry crowd that is actively lobbying lawmakers, however. The American Association for Justice, the country’s foremost advocacy group for trial lawyers, dispatched lobbyists in negotiations over the CARES Act and the previous coronavirus relief bill, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Both in-house and outside lobbyists for the trial lawyers worked, as one federal filing put it, “in opposition to efforts to grant liability relief or immunity for injuries caused by products required to be manufactured or whose manufacture is subsidized by either bill.”

That lobbying campaign comes as class action lawsuits stemming from the virus are in the works around the country. They’re going after companies ranging from Target, which plaintiffs in California claim falsely inflated the effectiveness of its hand sanitizer, to pharmaceutical firms over allegations that they misled shareholders and the public about the prospects for the development of coronavirus treatments, to hospitals over allegations they violated employee safety protections by exposing nurses to the virus.

At least six groups representing doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers lobbied Congress on medical liability issues in the first rounds of COVID legislation, according to federal filings. They include the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, the American College of Cardiologists, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

—with reporting by Lachlan Markay