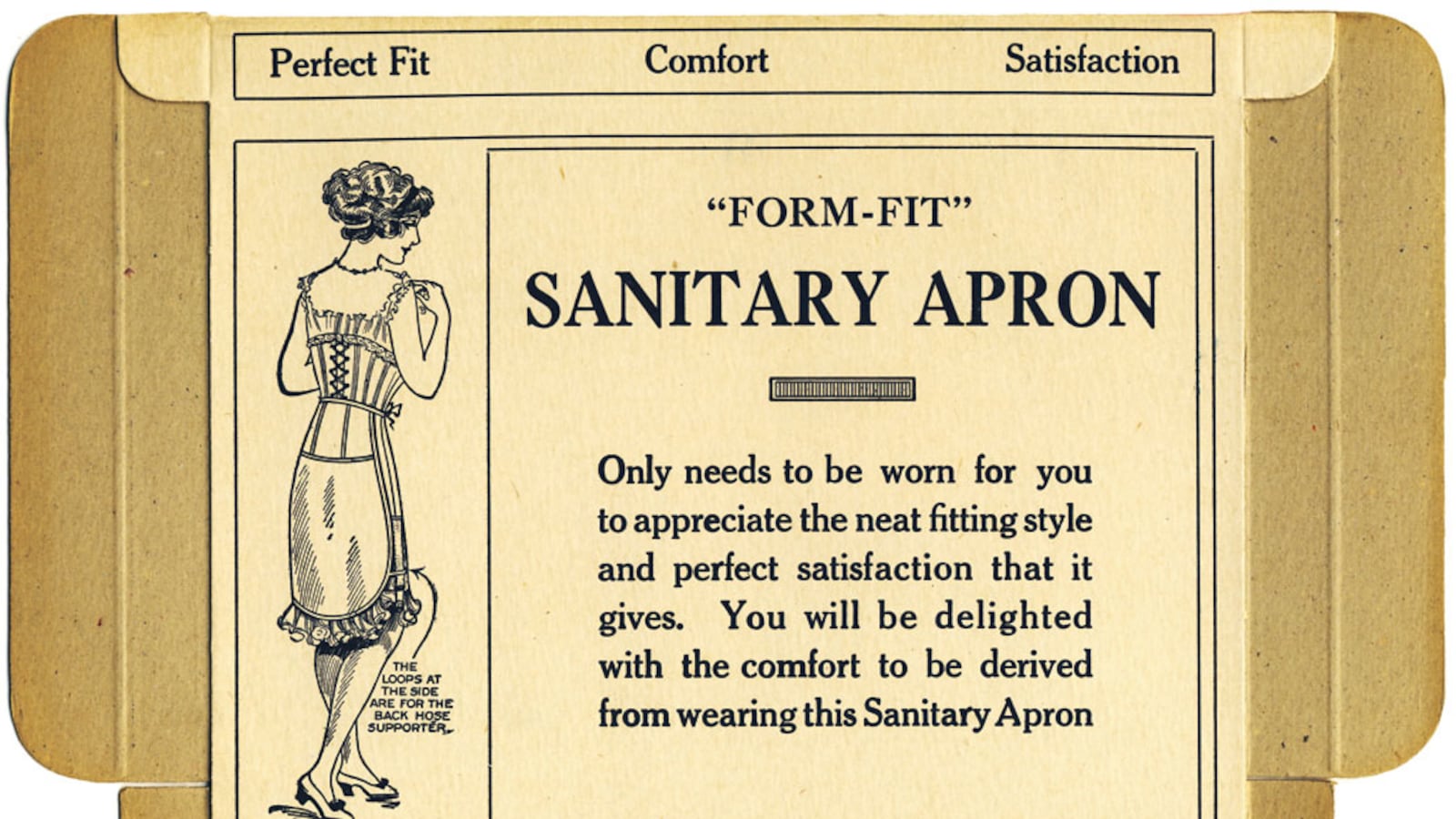

In the early 20th century, women could mail-order rubberized “sanitary aprons.” The aprons were worn backward under clothing, protecting dresses from stains. “Not being absorbent, they leave us wondering, where the hell did all the blood go?” authors Elissa Stein and Susan Kim write in Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

In the 1920s, stores began to carry disposable pads. Lest women feel too embarrassed to purchase them in broad daylight, Kimberly-Clark suggested shop owners display Kotex on the counter, next to a box for money—ensuring that the transaction was as discreet as possible.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Dr. Earle Haas, an osteopathic physician from the Midwest, filed the first tampon patent in 1931. Two years later, Denver entrepreneur Gertrude Tendrich purchased it for $32,000 and founded Tampax. Many women were initially squeamish about the concept of tampons.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

This ad is clearly trying to sell women on the tampon concept. Perhaps they got a bit carried away with the slogan “Tampax makes life worth living?”

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Beginning in 1911, Midol was sold as a remedy for headaches and toothaches, but it eventually became many women’s menstrual headache-cramping-bloating-blues reliever of choice.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Selling an idealized lifestyle as much as a product, Young and Rubicam’s “Modess…because” campaign for Johnson & Johnson lasted decades, from 1948 to the 1970s. The ads were shot by the era’s leading photographers and featured budding starlets in couture gowns. The product? Unglamorous sanitary pads.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Over time, print ads for feminine care products began targeting mothers, in the hopes of building a multigenerational customer base. What mom wouldn’t want to her daughter to use pads of “such gentle softness?”

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

For decades, Judy Blume’s young adult novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret has helped educate girls about periods and puberty. Since 1980, it’s also been one of the top 100 books that parents have tried to ban from school libraries.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

With feminism’s rise in the 1960s and 1970s, ads for feminine hygiene grew increasingly down-to-earth, featuring real products—including the first adhesive pads, allowing women to burn their sanitary belts once and for all.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Women experienced new freedom not only from traditional gender roles in the 1970s, but also from cumbersome menstrual paraphernalia like sanitary belts and clips, as adhesive pads hit the market.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Olympic gymnast Cathy Rigby is one of only a handful of celebrities over the years who’ve agreed to appear in ads for feminine care products. Getting a celebrity to “actually plug a plug, so to speak, is a rare event,” the authors of Flow write.

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin

Two years ago, the FDA approved Wyeth Pharmaceuticals’ Lybrel, the first “menstrual suppressant” that promises to halt women’s periods indefinitely. Have we reached the beginning of the end of menstruation as we know it?

Courtesy of St. Martin's Griffin