At every Broadway performance of Richard Greenberg’s baseball drama Take Me Out (Hayes Theater, to June 11), Michael Oberholtzer goes on stage hungry. Literally.

“There’s not really a methodology to it,” the actor told The Daily Beast. But it helps nourish the leering menace and explosive fury Oberholtzer brings to playing the violent, bigoted pitcher Shane Mungitt, for which Oberholtzer has received a Tony Award nomination for best featured actor in a play, alongside co-stars Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Jesse Williams. Take Me Out, first produced on Broadway in 2003, itself is up for Best Revival.

“I like to be hungry when I play Shane,” Oberholtzer said. “It’s not something I really decided to do, but I think Shane is hungry in some way, and being hungry on stage can create some readiness and immediacy to playing him.”

Mungitt, who his team-mates see as a dumb, hick-ish figure of fun before his depths of darkness fully reveal themselves, is also a dangerous psychological tinderbox, on a collision course with biracial, gay star player Darren Lemming (Jesse Williams), who is not about to endure Mungitt’s malign prejudice and insinuations or give up his position as the team’s most popular and well-respected player. Twists, tragedy, racism, and homophobia ensue—alongside a study of masculinity and the place of baseball in American life and culture.

The play recently made the headlines after Oberholtzer and Williams appeared in an audience-shot video of a key scene featuring the two actors naked; in this interview, Oberholtzer discusses his own “upset” at the release of the video online, and his and the rest of the cast’s determination to carry on giving their all in performances.

Late in the play, Mungitt explodes in an ugly, raw fashion, making Oberholtzer's performance one of the most commandingly terrifying this season on Broadway. “It’s more of a challenge to be in it fully, and modulate it throughout the week,” Oberholtzer said of the velocity of fury he musters. “I have a little secret. I always try to put a little extra sauce on it at the Sunday matinee performance because it’s the end of the week.”

This critic saw his intense performance on a weeknight, so can only imagine what extra dollops of “sauce” those Sunday audiences get splattered with.

“Anybody who gets a Sunday night ticket, for the last show of the week, whatever is left in my tank, you’re going to get it all,” Oberholtzer said, smiling. “To be clear, everybody gets it all, every performance, but Sunday is a day there might just be little more. It’s because I know I have Monday to rest.”

He pays tribute to his “very good scene partners, Williams and Patrick Adams (Kippy). “You can’t short-change working with good people because they are constantly pushing you. You’re not up there having this crisis alone, it’s being motivated by the behavior of good actors. I have to give them a lot of credit for helping me with it every night.”

Of the Tony nomination, Oberholtzer said, “It’s absolutely wonderful. I spent a long time in my acting career and life wanting to be a working actor. Being able to make a living as an actor is no small feat. That sucks at times. Then to have the opportunity to work on Broadway a few times is wonderful, and be able to have the opportunity to play a really good part is another big accomplishment for an actor, and to be recognized for work in this way is ultimately very humbling. It is definitely not something I take for granted.”

He has been singularly focused on honing his character, he says, and was “absolutely surprised” to get the Tony nomination.

How does he make Shane so terrifying from minute one (coiled spring) to end (explosively uncorked)?

“I submit to it. I surrender,” said Oberholtzer. “That’s the most challenging thing that requires preparation. Richard Greenberg wrote this really dynamic part and did it so well that as an actor if you can understand what you’ve been given is so well crafted, then the job really becomes about surrendering to that and giving everything it asks and demands of you—so, it’s about getting out of the way, frankly, and trusting it will carry you.” (More prosaically, he stretches and hydrates.)

As to whether Shane is racist, homophobic, evil, lost, broken, or perhaps a combustible mixture of all of that, Oberholtzer said, “Based on the text, I believe that what he is saying and doing is coming from a place he believes to be true, even though it is misaligned from the rest of society. It makes sense to him, and I trust that. I think human beings can certainly understand that. We all know people who believe shit we know is insane, or racist, or crazy. But they’re decent in some other areas of their life. Maybe they even have a high IQ or a high standing in society. This is my roundabout way of saying Shane is authentic unto himself. Darren and Kippy poking and prodding and getting in there is ruffling him up, exposing this, and igniting that.”

Left to his own multiple inner demons, Oberholtzer thinks Shane would “shut the fuck up and play baseball. I don’t think he has the compulsion, or need to be a public figure or famous. I think he’s very simple in that way.”

After you’ve seen Oberholtzer’s performance you might wonder how he lives with his railing, scary alter-ego, or how he winds down from playing Shane night after night.

“I don’t live with him 24/7, and I don’t really inhabit that headspace,” the actor said. “But the frenetic energy and exhaustion of it most certainly lingers. It takes a while. I take the train home to Yonkers [where he lives with his wife and two children]. Playing Shane is mentally invigorating and physically exhausting. I’m buzzing mentally for a long time afterward but physically depleted. It’s really one of the most exhilarating feelings, and one of the things I absolutely love about this job.

“It’s one of the great gifts that you can be given as an actor—a part that challenges you and demands of you every night. You’ve just got to do it, man. You’ve got to go to the high dive and just jump. You can’t make concessions, you can’t make apologies. It may sound weird, but you have to honor the truth of that person, even though it’s really reprehensible and offensive at times. People like this exist. People think like this, and internalize and misdirect their anger and hatred.”

Shane, Oberholtzer says, really has nothing going for him, except the “lottery ticket” of his baseball skills. “Then he watches his life go down the fucking toilet and he can’t do anything about it. And he’s got nothing to turn to and nothing to back it up. However you feel about him as an audience member, Shane is fighting to the end.”

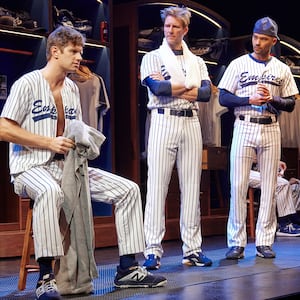

Michael Oberholtzer, foreground, and the cast of “Take Me Out.”

Joan MarcusOberholtzer said he has found something in Shane to empathize with, aided by Greenberg’s writing; for his portrayer, Shane’s most hateful statements are indicators of his brokenness as a person. “I see that as his DNA, somewhere in there there’s a boy—a broken, fragmented, arrested individual that has not fully formed.”

As anyone who sees the play knows, the lines that Shane says are met with voluble disgust by many in the audience. Oberholtzer has had to find a way to say them, and say them right.

“As a company, these were subjects and ideas we had to approach in rehearsals in the right way,” Oberholtzer said. “We had to understand what we were saying in the rehearsal space and also in a scene.”

That helped create a “safe space” to build his toxic character, but Oberholtzer admits, “I had fear going into it, I really did. I really felt for a while that there could be no way somebody like this could be on a stage in today’s society. People in the audience are like, ‘Come on,’ when he speaks. You hear the disgust from the audience. From a performance standpoint, that reaction is everything. It means you’re landing—the jump, the turns. You’re telling the story, hitting people in the solar plexus in their fucking guts, to the point where they’re verbally expressing however they feel about it. As a performer, that reaction is telling you to keep going.

“Internally I’ve had a lot of complicated feelings about saying these things over time—initially, most certainly, and as we have gone on that has evolved. For me, there are certain things in this script you can’t say and then apologize for, because if you do you’re doing nobody no good. You’re wasting time. You’re not figuring anything out. You’re still potentially offending people saying the things, but you’re not saying them as they should be said.

“I had my feelings. I kept my feelings. I shared my feelings with some people. But when the time came to do my scene and develop it I had to get out of the way and say, ‘This is the story we’re telling. It’s one part of the story on this journey and we have to make sure we connect from here to here to here, and we have to get here by the end. For me, that demanded a lot of work. I had to focus on all of that rather than how people were going to perceive what it was.” He laughed. “If I’m going to die on this sword, I’m going to die on the Richard Greenberg sword on Broadway.”

Of the funnier things he has heard the audience shout at, when his character announces he’s from Arkansas, he has heard whoops of “Yeah, Arkansas” from the audience.

Hearing Shane’s bigotry in the wake of events like the recent racism-rooted massacre in Buffalo makes his words of hate “so on the nose, hearing some in a public space even under imaginary circumstances.” He is also aware of the audible shock of the audience as the play’s final twists reveal themselves.

The fact that Shane is so apart from his teammates is not mirrored backstage, where the company has always been “tight” as co-workers and buddies said Oberholtzer, regularly going out for lunches together. “I have never felt the need to emotionally prepare in another room, or to ask people to leave. What felt necessary was developing the overarching camaraderie we have as a company. We’re telling this story as a group of men about homophobia, about a person of color in this American institution, what democracy means, what having English as your second language means, and what it means to hold beliefs like Shane’s. All of the characters inhabit all of these ideas that create the fabric that is the play. The rest of the cast invigorates me. They support me, they root for me, and it’s vice versa too.”

“You have to give yourself over to the nudity”

While many actors in the show go nude for collective shower scenes, Williams and Oberholtzer share a particularly charged nude scene, which was covertly filmed and released online. Oberholtzer did not initially find the play’s nudity easy.

“There are plenty of people out there dying to do stuff like that. But no, that was definitely not something on my bucket list, or ‘things I gotta do before I do before I die,’ y’know,” Oberholtzer told The Daily Beast. “That being said, it became for me what I believe the general consensus is for those that see the play—which is that the nudity is an integral and necessary part of the story we’re telling.

“You can’t extricate the nudity from what we are talking about. You have to give yourself over to it. The story has to become more important. I also can’t take ‘Michael’s insecurity’ on stage in a scene like I do with Jesse because that’s not what the scene is asking for.” I do whatever I have to do to reconcile all of that to get to a place where I can actually live as this other person and think about what they’re thinking about in that moment. In that sense it’s quite helpful you have other things to think about, as the character of Shane, that are more important than being naked.”

Doing the show, and hearing the discussions about nudity, have made Oberholtzer think about attitudes towards the naked body more generally. “I don’t want to say the nudity is liberating because it’s not liberating but it’s like, ‘What’s the big deal?’ You start to realize—I’ve started to realize—the nudity question is more a reflection of other people’s values, mores, hang-ups, and insecurities. When people talk and ask you about it, you feel it says something more about them than anything else, and then there’s another overarching conversation about the naked body in public space.”

The video featuring him, which went public a few weeks ago, was condemned by his fellow actors, theater, and unions, as a gross and illegal invasion of his and Williams’ privacy. Had Oberholtzer seen the public airing of such material as inevitable, even though audience members are asked to deposit their cellphones in a locked pouch to preclude filming and the taking of photographs?

“In a way I did I think it was inevitable, In the beginning, we didn’t think it would be conceivable that we would be able to build an infrastructure which would stop it. But the pouches turned out to be quite successful, and it has been quite beneficial for the theater at large, putting your cellphones away so you can be with us in the moment, taking the story in and having that experience.”

Oberholtzer makes clear he is only speaking for himself when he says he became “less and less preoccupied” with the idea that the taking of images would happen. “We weren’t hearing cellphones going off. Then of course it happened, and it wasn’t even a cellphone we were told. Somebody decided to break an agreement, do something that was illegal, and violate other people’s consent—and that’s very, very upsetting.” Oberholtzer took comfort that there was such a strong reaction from the theater, unions, and legal representatives “who fixed this situation as best they could.”

As a company, Oberholtzer said, “We decided we were not going to let this event, this thing that happened, overshadow all of the sacrifices, hard work, and commitment that we have put into this story that we are all very proud of. We wanted to make people understand that.” Oberholtzer’s own feelings remain “complicated” around what happened, but he says he and the rest of his colleagues had been determined to “try to move past it.”

The cast of “Take Me Out.”

Joan MarcusHe sounds utterly focused on playing Shane in the strongest, most rounded way possible. “My experience of playing Shane, living through Shane, his problems, and saying what he says, is nothing like the audience’s experience of watching Shane,” said Oberholtzer. “That’s what is beautiful about it. That’s why I love hearing people say what their experience of Shane and the play is because I know it’s nothing like what I’m doing, thinking about, and what’s driving me. That’s what I take pride in as an actor.”

While Oberholtzer can listen and marvel off-stage to the parts of the play that don’t involve him, he doesn’t have the experience of the audience threading the play together as they watch it, “sitting in the 14th row, and going ‘Holy shit.’” He took real pleasure in how awed family members were when they came to see the play, “overloaded” in the most dazzled way by the play, its themes, characters, writing, acting, and spectacle.

Shane’s volcanic anger, terrifying to the audience, is not hard to reach tonally, said Oberholtzer. “But it’s hard to maintain and make authentic. Anger is really the tip of deeper things. As an actor, to get to anger is not the most challenging thing, it’s what lies underneath the anger you need to pay attention to because not all anger is the same.

“Understanding where anger comes from—that’s what the job is, that’s what those moments are, connecting to something that’s real. That’s why they call it self-righteous anger. It’s like a drug. You can get off on it; the endorphins are going and all the oxygen you’re taking in. The moments when Shane is absolutely attacking somebody—we see it everywhere today, we see it on TV. There’s so much vitriol and hatred in our public officials.”

Oberholtzer makes the point that—inconceivable until recently, with the proud voicing and embrace of all kinds of bigotry by right-wing politicians and online voices—“you could make the argument that someone like Shane Mungitt would now have a support group somewhere, there’d be a GoFundMe page for the guy, ‘this persecuted guy,’” as his right-wing supporters would say.

“Award nominations are very important, but they’re not destinations”

“There’s some milk in the refrigerator,” Oberholtzer says gently to his two children, as they clamber over him while he talks about his childhood in Indiana. His mother was a supply teacher for many years and his father worked for an electric company—“one of those people, the last of a dying breed, who worked in the mailroom and then retired 50 years later. He loved it.”

Growing up, he didn’t know anybody in show business. “Nobody where I lived was even tangentially connected to show business.” Yet acting was always the thing he wanted to do, although “it wasn’t something till later in life I made the decision to hop on this train and really make a go at it. But this was always the thing that had the most pronounced and clearest north star for me. It’s always been there.”

As a little boy, Oberholtzer says he performed in “little operettas and Christmas plays. I always enjoyed singing, dancing, and performing quite frankly. At a young age, I enjoyed being the center of attention. I really loved playing to adults, and trying to get adults to laugh. Getting kids to laugh was play. I knew if I got my grandfather and neighbors to laugh I was on to something.”

A friend acquired one of the first camcorders, and the two of them would go to a local library to film SNL-style skits. He did an interdisciplinary arts degree at Columbia College Chicago, where he performed in plays and did a lot of dramatic, fiction, and screen writing, and developed scripts. Oberholtzer’s drama teacher suggested he go to New York and work with a teacher, Maggie Flanigan, who helped give him “a foundation and bedrock in acting.”

Oberholtzer humbly describes himself as “a textbook actor,” who corrects any notion of what “a big break” might be. “Everything when it came was a big break, let me tell you. The first time I got a $50 check for a Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival I fucking framed it, and then I realized I had to cash it and had to take it off the wall. I was so proud.” His first job as an actor in a play was in a revival of Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy, which got him his Equity card, “and a $500 stipend at the end of the first rehearsal and $500 at the end. It was thrilling. I remember calling home and saying that I had made it. ‘I’m a real actor. Somebody is paying me to be an actor.’”

Getting a role in Law & Order was a “big deal,” and the next plays. “Every job is great when you’re wanted, when they’re excited about you.” The multi-award nominated devil puppet-featuring play Hand to God brought more success and visibility. “I thought, ‘My career is going to go on this steady incline,’ then I started to understand this business doesn’t work like that.’” One TV show didn’t work out, “and it was back to the drawing board.”

Oberholtzer and Greenberg developed a professional relationship when he appeared in the latter’s play The Babylon Line, first reading the role of Shane in Take Me Out at readings in 2016. Oberholtzer doesn’t have dream roles, he says, but rather hopes to keep working with interesting people on challenging projects.

Oberholtzer may not have sorted his Tony Awards night outfit out yet (“Hopefully I won’t be in a bathing suit”), and is enjoying his deserved moment of recognition while remaining healthily circumspect.

“Award nominations are very important, but they’re not destinations,” Oberholtzer told The Daily Beast. “It’s important for me to keep that in perspective, because there’s still a lot of work to do out there. I want to be challenged, find good people, be a part of stories. If the visibility of the nomination helps with that, wonderful. It’s very special to be part of the season that Broadway came back, and also really special to be part of the 75th Tony Awards. Something about that is beautiful. I love all this stuff. I embrace all of it. I take all of it in.

“So much of an actor’s life is about obscurity, kicking around pavements and doing stuff people don’t like, or people don’t see. It would not be appropriate to not have gratitude for something like this and I certainly do. There’s nothing about it which isn’t great. I never had an experience like this, not even close. I’m not naïve enough to think this will come down the pipeline on the next go-around, although hopefully I’m in acting for the long haul and there will be opportunities to play other great parts.”

The wizened actor within also leads Oberholtzer to note that before Take Me Out, it had been seven long years since he was last on Broadway. “I know really talented people, people arguably more talented than I am, who have never had an opportunity like this—to never have the opportunity to be in a Broadway play, let alone play a part like Shane Mungitt.”

“It’s going to be difficult” to leave Shane behind at the end of Take Me Out’s run, “because of what this character means to me and what he’s given to me and what he’s asking of me every night,” said Oberholtzer. “You don’t get opportunities to work like this very often, I know that much. So, for all Shane’s flaws and all his problems and controversy, to be able to play full-out like this as an artist is everything, man. It’s everything. That’s why I love him. He makes me do that.”