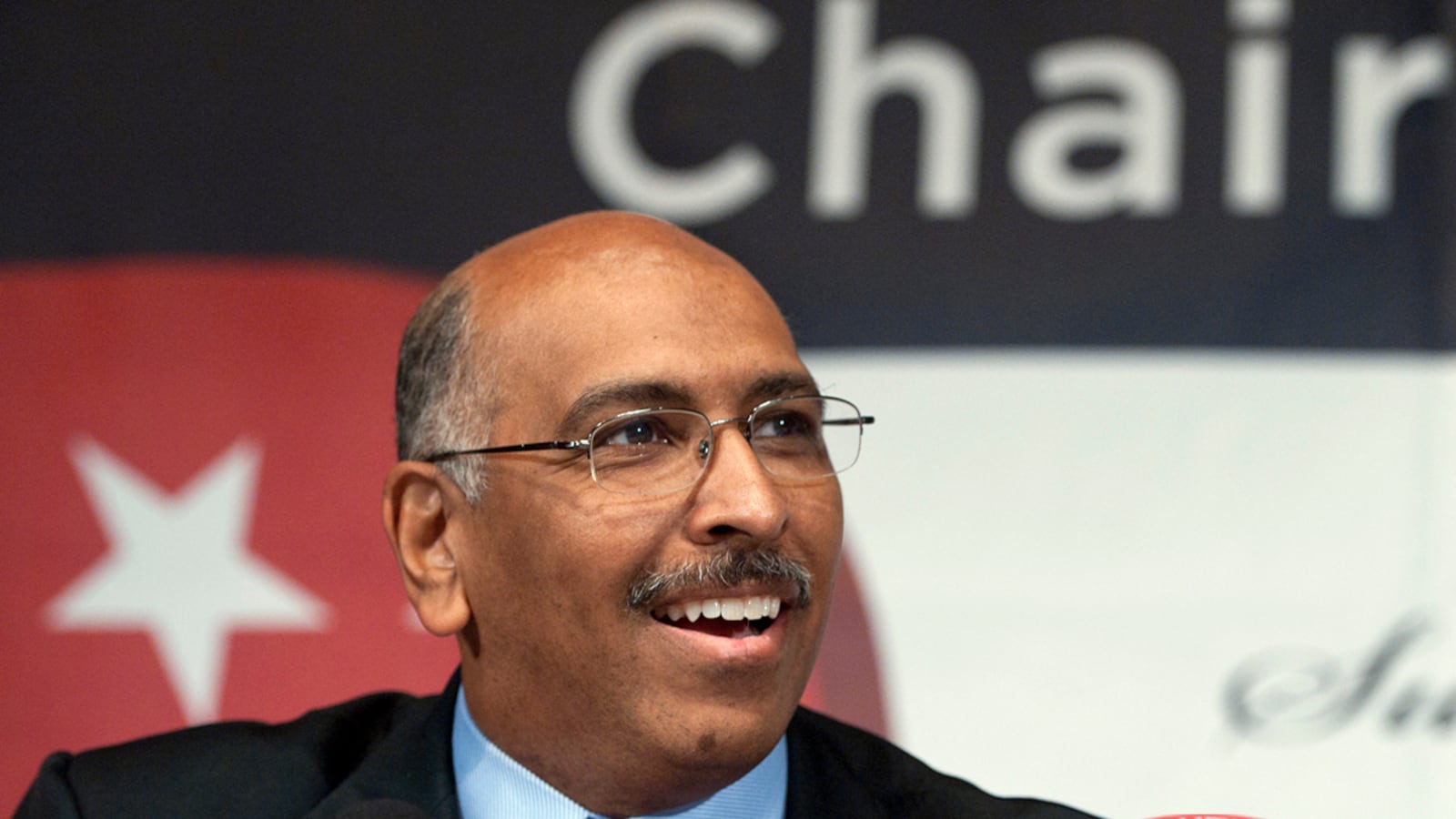

It has been nine months since Michael Steele was unceremoniously booted from the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee, abruptly ending his rocky tenure as the first African American to lead the Grand Old Party.

The soon-to-be 53-year-old Steele, who dropped his quixotic reelection bid on the fifth ballot, has moved on with his life. Today he gives paid speeches, works as a Washington-based international business consultant, and also appears on MSNBC as an on-air political analyst, handicapping the presidential races of Mitt Romney, Rick Perry, Herman Cain and Barack Obama.

But a mere nine months is clearly not enough time to have healed his wounds or soothed his anger.

“All that is bullshit! Quote me!” Steele erupts when I ask about all the brickbats he absorbed during his two years as party chairman—which were mainly criticism from his many detractors in the Republican establishment that he raised too little, spent too much and liked to live high on the RNC hog. “Everyone who’s out there peddling that narrative never gave a single example—because there was none!”

We’re sitting at a prime table at Bobby Van’s in downtown D.C.—one of Steele’s favorite lunchtime haunts—and he’s doing his best to obliterate his media image of hapless profligacy, what with private jets and limousines, a convention trip to Hawaii and a night of partying at a West Hollywood strip club—all charged to the RNC.

“I flew coach, I booked coach, but then I had my own miles that I used to upgrade,” says the 6-foot-4 Steele. “We’d have events at the Four Seasons, and I stayed at the Marriott or the Holiday Inn.” As for the notorious Voyeurs Club incident, in which a donor was entertained at a topless venue known for bondage and girl-on-girl performances, “That was just idiocy on the part of a staffer. I wasn’t even there,” Steele says. “I was at our winter meeting in Hawaii. And that was a big deal for us. ‘Oh my God, he’s going to Hawaii!’ But it was cheaper for us to go to Hawaii than to hold an event here at National Harbor.”

Steele says a turning point in his tenure came when RNC members voted overwhelmingly to a take out a $15-million line of credit over his objections, he claims, “because I’m a Republican and I didn’t want to spent money we didn‘t have.” Among those who favored the loan, Steele says, was RNC general counsel Reince Priebus, who later used fiscal irresponsibility as an issue in his successful campaign to unseat Steele as chairman. “Some of the people egging me on included the current chairman, who signed off on this deal and thought it was the best thing for me to do,” Steele says. “And to sit back now and act like, ‘Oh my God! We have all these problems! All this debt!’ Well, motherfucker, you’re the one who voted for it. I didn’t vote for it. I’m the one who said no.”

Steele reserves special scorn for two people: Washington Times political reporter Ralph Z. Hallow, who orchestrated a drumbeat of negative stories about Steele’s administration, and sometime adversary Karl Rove, the establishment guru turned Fox News personality whom Steele derides for arrogance. “Or, as my mama would say, showing yo’ ass.”

After all, Steele argues, if he was such a terrible party chairman, how did Republicans manage to gain six governor’s mansions, pick up six seats in the Senate—including the one in Massachusetts held for 48 years by the late Ted Kennedy—and sweep the 2010 House midterms by a stunning 63 seats, knocking the shell-shocked Democrats from power?

“My style is, I’m an honest broker,” Steele explains. “I’m not going to sit here and lie to you. I don’t do talking points—which is a problem.” He grins sheepishly. “Yeah, I’ll take your talking points and I’ll digest them, but I’ve got to put it in my own words, in my own way, to make it authentic. I’m not going to say the sky is blue when it’s really gray—because people aren’t stupid. And if you continue to treat people like they’re stupid, you wind up with the results you’re seeing now—an outraged public.”

Indeed, his style seems better suited to cable television than party bureaucracy—and the former chairman, a savvy observer with an appealing sense of humor about himself and the process, seems far happier as “Michael Steele Unplugged” than when he was struggling against the shackles of the GOP machine. He says that when he was chairman, he frequently directed the RNC communications staff to set up media interviews to put out his side of the story. But I pointed out that my repeated attempts to meet with him were rebuffed by those same staffers.

“I think a lot of it was, ‘We don’t know what he’s going to say,’” Steele explains. “My attitude was, look, if I made it this far without all that—if what I had to say was so out there and so crazy—I wouldn’t have been successful as lieutenant governor of Maryland [an elected position he held from 2003 to 2007, interrupted by a failed campaign for the U.S. Senate], as the head of GOPAC [a political action committee focused on state and local candidates] or anything else I’ve done.” Steele says he couldn’t help but be amused by Republican establishment’s hero-worship of the outspoken governor of New Jersey. “I was laughing,” he says. “All these people are asking Chris Christie to run, and I’m saying be careful what you wish for.”

Steele, who spent two-and-a-half years in an Augustinian seminary and almost took his priestly vows before plunging into politics (and becoming a lawyer to earn a living), has a complicated relationship with the GOP. Growing up in the majority-black District of Columbia—where Republicans, especially black Republicans, were all but invisible—Steele looked for role-models among the city’s Democratic office-holders.

“I didn’t come up through this political system the way a lot of these Republicans did,” he says. “I wasn’t hanging out in College Republicans and Young Republicans and central committees, because I grew up in D.C. I didn’t have that structure. I didn’t learn my politics from the likes of a Haley Barbour”—the governor of Mississippi and former RNC chairman who, much to Steele’s disappointment, worked behind the scenes to foil his reelection bid. “I learned my politics from the likes of John Ray, Marion Barry and Joe Yeldell, who were the political-leadership Democrats of this town. I learned how they operated. I learned a lot from them.”

Yet as he moved up the ranks of the Maryland Republican Party, becoming chairman of the Prince Georges County and then the statewide organization, he was spurned by some as a traitor to African American interests. In one notorious incident, after a debate during his 2002 lieutenant governor’s campaign, a fusillade of Oreo cookies was tossed at Steele by Democratic activists in the audience. “I made the joke, ‘Got milk?’ Because I like milk with my Oreo cookies. Of course it was hurtful. But what am I going to do about it? I’m not going to sit there and start whining and moaning about it.”

It’s hardly surprising that Steele felt a certain kinship with Barack Obama, despite their policy disagreements, and hoped to befriend the future president shortly after he was elected to the Senate from Illinois in 2004. “I have tried, going back to when I was a lieutenant governor and he was a newly minted freshman senator, to meet one-on-one to get to know him,” Steele says. “Because, at that time, we were the only two African Americans holding federal and statewide office.”

Mutual friends encouraged a get-together, believing that the optics alone would be good for the country. “It went beyond politics and policy,” Steele says. “It’s the personal affirmation of the journey and, more broadly speaking, affirmation to the 14-year-old black boy who is looking at two choices. He could be taking up the life that will wind him up in jail in two years, or he could be following the path that will lead to the opportunity to sit in one of our two seats.”

Steele still sounds stung as he recounts what happened next.

”I told my staff I’d like to invite the new senator to dinner to welcome him to my hometown, Washington, D.C. I thought it was important to get to know each other. Even though we’re philosophically going to be on different sides of the equation, there were other aspects of our unique histories that would give us a chance to see the world through each other’s eyes. But that never happened. We were told by his Senate office that they didn’t see a need for the two of us to meet.”

Steele, on the other hand, is heartened by the rise of Herman Cain, another African American who’s making a splash in American politics but is also, perhaps just as important, rebuking the conventional wisdom of the chattering classes.

“What it means is that there’s a life-energy beneath the surface that’s driving the body politic,” says Steele. “And that’s outside the reach and consciousness of those who think they know what’s going on, and getting it wrong every week. So Herman Cain is the flavor the moment? Well, okay, that may be true, but the reality is that he has an impact. He resonates with a lot of people in the party. Now, I would prefer that he not be on a book tour in the middle of running for president, but this campaign has been doing it differently from the very beginning.”