Apparently, there will be no sweeping effort undertaken to humanize Mitt Romney at this week’s convention. He told USA Today that during the daytime sessions, there will be “a series of vignettes, so people who attend the convention will get to know me a little better,” but during primetime, when millions are watching, “we won’t be talking about my life.” It’s the right decision in the sense that there’s almost nothing about his life that’s the least bit emotionally compelling. But it’s also a telling one, because it means the campaign is basically going to be: Vote for me, I’m white, and I’m not a socialist.

Gallup found last week that Barack Obama outscored Romney by 23 points on the likability scale, as 54 percent said they found Obama likable compared to only 31 percent for Romney. Normally a campaign would be quite worried about this, and rightly so. I’d rate it as Romney’s biggest problem, more than his positions and his incessant right-wing pandering (I guess those two are the same thing). People don’t normally vote for somebody they don’t like, especially for president. A state legislator, a congressman, a senator, even a governor—you can forget who that is, if you have a mind to; go days or even weeks without hearing his name. But the president? You can’t avoid the guy.

And so every presidential campaign of the television age has pushed the touchy-feely button. Al Gore and his sister, George W. Bush and the bottle (and Jesus), Bill Clinton and the abusive stepfather, Bob Dole and the war injury. And almost every winner has been likable enough. Bush was definitely not my cut of steak, but I could imagine that if he were a normal guy and I ended up next to him on an airplane, I could carry off a reasonably happy chat with him about golf or something, assuming a mercifully short flight.

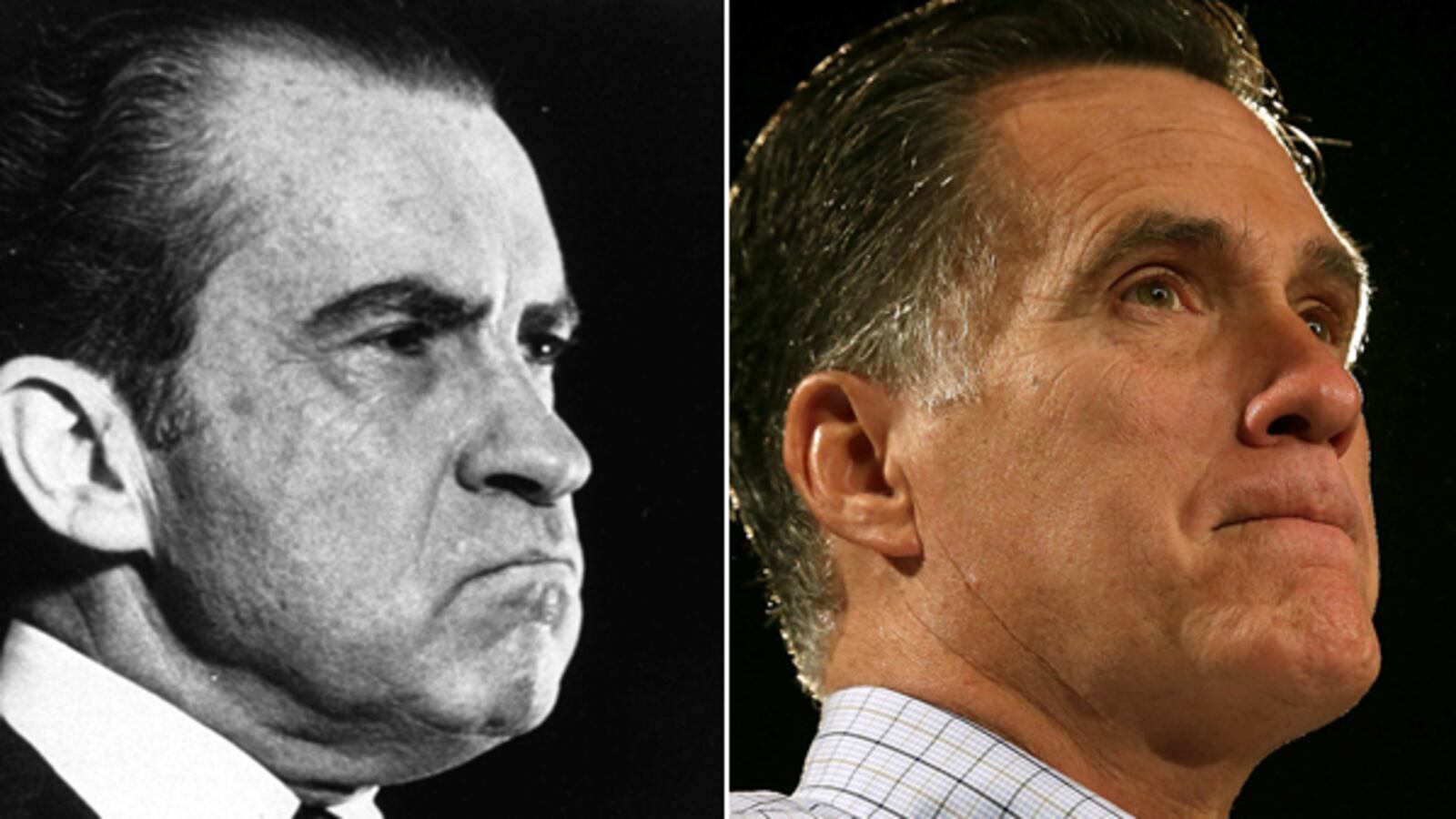

We have had, in the modern era, just one truly unlikable president. Dick Nixon, of course. And it turns out that there are points of similarity between Romney’s and Nixon’s campaigns that aren’t instantly apparent but are worth fleshing out. The campaigns resemble each other in that both are built far more around negative than positive selling points. With Nixon, the argument went that you needed to elect him to preserve law and order, which he said was at risk of very survival if Humphrey won; to keep the blacks and the hippies and the pinkos at bay; and because he had a secret plan for quick victory with honor in Vietnam, which turned out to be so secret that he continued the war, even expanding it into Cambodia, for another seven years before we finally lost it.

Romney’s arguments just need a fresh coat of paint to keep up with the changed times, but they’re roughly the same. Our free-enterprise system, our very way of life, is at risk if Obama is reelected; he and Paul Ryan are needed to keep society’s freeloaders and moochers at bay. There is no precise analog for Vietnam, I suppose, but it is certainly fair to say that Romney’s foreign-policy offerings, delusional though they are, are once again more about Obamian perfidy (apologizing for America, etc.) than any vision of his own.

Romney is (as far as we know) not the steel-cold sociopath that Nixon was. I’m not comparing the two men personally. In that way they’re quite different. Nixon, who grew up poor and fought his way into higher society while developing sharp distrust and raging hatred for Jews and elites, embodied white middle-class revenge far more naturally than Romney does. He’s too dorky and entitled to really seethe with that hatred, go to sleep with it and wake up with it, the way Nixon did.

They’re also eschewing biography for different reasons. By 1968 Nixon was so well known that he didn’t have to introduce himself to America; America got to know the Nixon family in the Checkers speech 16 years before. Romney’s life simply doesn’t provide the material (except for his wife’s multiple sclerosis, which evidently will be given the soft-focus treatment).

And yet, different as they are, their campaigns, their appeals, are undeniably similar: Nixon led, and Romney is now leading, a vengeance campaign against an Other America, an America their supporters despise. Romney’s is a campaign that seeks to win, that can only win, by dividing the country into an “us” and a “them.” I confess that I’ve been genuinely shocked by the baldness of Romney’s lies about welfare and Medicare and about the way he’s racialized this campaign. I guess that’s precisely because, whatever he seemed, he did not seem sinister like Nixon.

And he may not be. But he is clearly a man who will do and say anything to be president. And when he accepts his party’s nomination this week, and all those general-election dollars are unlocked and converted into negative ads in swing states, we’re going to find ourselves in uncharted waters—a candidate and his affiliate groups with hundreds of millions of dollars to spend, virtually all of it attacking the other guy. Obama may emerge from that onslaught heavily damaged and less well liked, but Republicans should ready themselves for the divinely just possibility that Romney might end up even less well liked too.