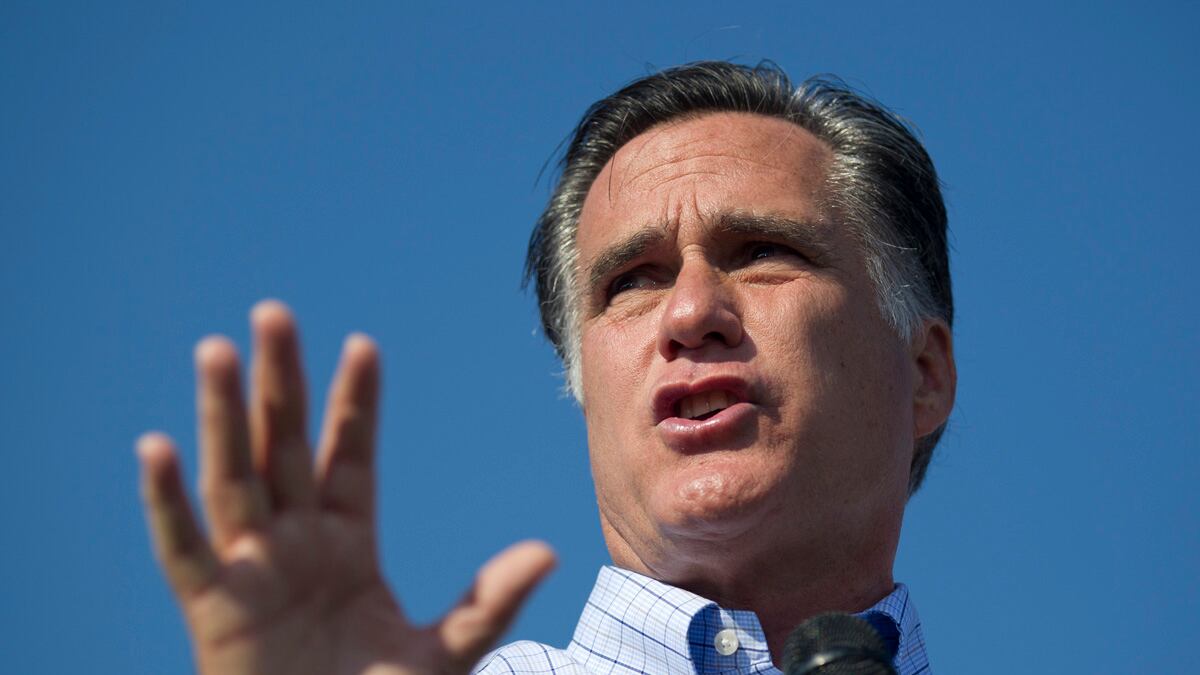

Mitt Romney’s nomination speech is receiving final edits as you read this—examined to make sure every essential theme is included, every phrase shined and sharpened.

But Romney has an additional burden in this nomination address—he needs to fill in the missing character narrative at the core of his campaign.

JFK had the searing experience of PT 109. John McCain survived years in a Vietnamese P.O.W. camp. Bill Clinton stood up to an abusive stepfather. George W. Bush overcame the temptations of drink and found a fortifying faith.

We expect our presidential candidates to come with a character narrative, however big or small, a hero’s journey of suffering and redemption that informs their judgment, arming them with empathy and wisdom once they reach the Oval Office.

Mitt Romney’s blessing is his curse in this regard. He has lived a life of privilege and discipline animated by ambition. He was the son of a CEO and governor. He famously protested in favor of the Vietnam War but never served. He got a JD/MBA from Harvard and soon found extraordinary success in private equity, which would snowball into a quarter-billion dollar fortune, made meaningful by a lifelong love and five healthy children.

He has lived a life of great success but little suffering, at least on the surface. He has been tested, but in the boardroom rather than the battlefield.

This missing character narrative compounds his core problem of relate-ability. After five years of running for president, Mitt Romney has not put forward a character narrative at the core of his campaign biography.

There is at least one clear contender—Mitt Romney’s near-fatal car crash as a young man on a Mormon mission in France. He initially was written off as dead, and a passenger died. The wreck was not his fault, and the recovery took months.

But Romney is reluctant to talk about this experience, as he is about so many aspects of his personal life. He is an unusually self-monitoring man. In his nomination speech, Mitt will need to decide whether to take the risk of intimacy—revealing this or some other core wound that he faced and then overcame.

This risk of intimacy will require Mitt talk about two things he has avoided—his Mormon faith and his time in France. Neither territory is traditionally considered a campaign asset. But they are core facts of his life which helped shape his character.

Mitt Romney is that rare person who seems to have exemplary personal character. Stories abound about his private charity—not just tithing, but personal outreach to neighbors in need. And it seems clear that his personal character is the direct result of the impact of the Mormon faith of his life. That is a story of the power of faith to shape character no less powerful that George W. Bush’s personal turnaround after private meetings with Billy Graham.

Mitt’s beloved father, George Romney, was not as reluctant to speak about his Mormon faith—he gave extensive interviews on the subject in the 1960s— and yet that was not what defined his often courageous political career. But the absence of straight talk by Mitt Romney on the subject has allowed other narratives to talk hold and made some stories—like the Washington Post piece about him hazing a fellow student in boarding school by cutting off his hair—seem plausible, running the risk of defining him in the absence of a positive narrative he puts forward.

Reflexive partisans will say President Obama was elected without a character narrative—after all, he never served in war and achieved the paramount political success at a young age. But they forget that he was famously raised by a single mother on food stamps, for a time, and achieved the American Dream in short order, almost alone. He also benefitted enormously from a historical narrative as well—overcoming the very real discrimination on the basis of race that formed the fault lines of our nation from the original sin of slavery to the present day. His candidacy promised to heal that divide, and that is as big a character narrative as could exist.

The same sweep of history is not available to Mitt Romney, but if told honestly, his own story will offer signs of struggle and success that his fellow Americans can take some accessible inspiration from. Taking this risk of intimacy could pay real dividends by helping to answer the enduring question of “who is the real Romney?” And in the process of being genuine, he might find himself genuinely admired.