The Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington will be officially dedicated on Sunday, six weeks after Hurricane Irene forced the original ceremony to be postponed. The 30-foot white granite likeness of the civil rights leader, shown unsmiling and with arms crossed, is drawing big crowds, though not everyone is happy with the statue’s stern demeanor, or the fact that it was made in China and sculpted by Chinese architect Lei Yixin.

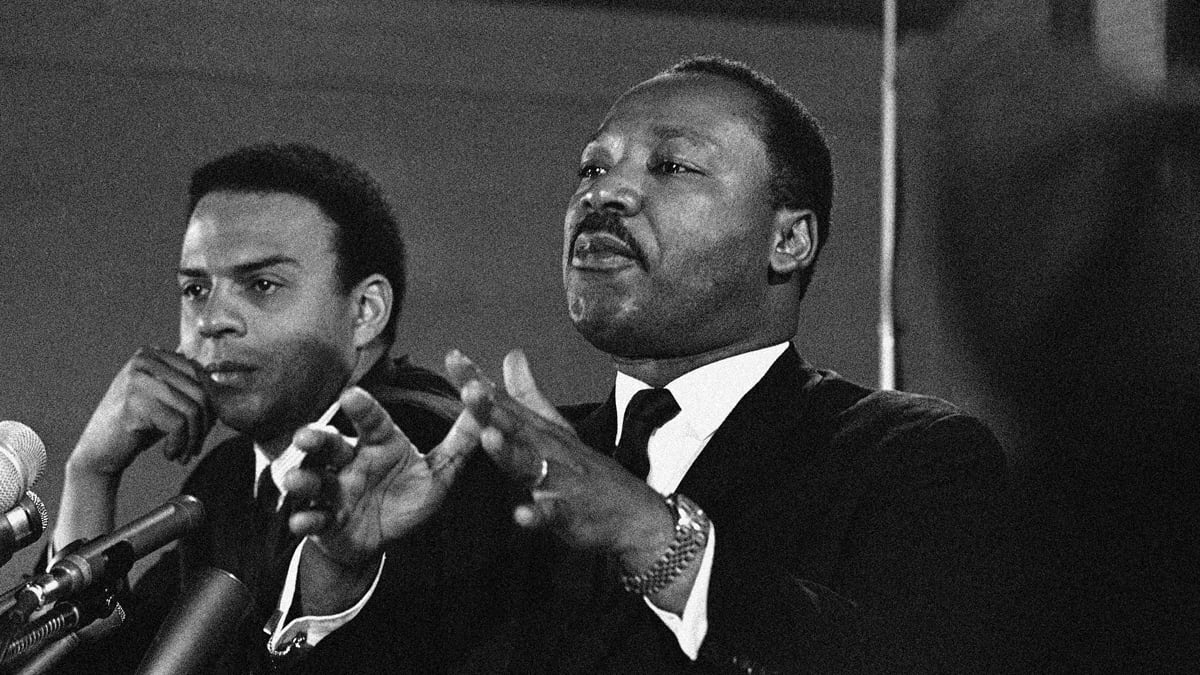

When King’s former longtime lieutenant, Andrew Young, views the memorial, he knows the 5-foot-7 King would be pleased with his towering stature. “He thought all his life he was too short,” Young says. “Even Coretta when she met him, the first thing she thought, he’s too short; second thing, she didn’t like preachers.”

Young likes the memorial, and sees the choice of a Chinese architect as prophetic, since the Chinese are likely to have problems with minority populations asserting their rights in the future. Just as Thomas Jefferson and George Washington are part of a democratic vision for the world, Young sees King’s status as he stands among the founding fathers on the mall in Washington as “testimony to the global vision of non-violence.”

King often used the expression that is carved on the south side of the sculpture, “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” Young thought for a long time it was just poetry, but came to realize it was the perfect metaphor for the mountain of opposition and resentment King and the civil rights movement faced.

When Young tells stories about Martin and the times they shared, you have to remind yourself that he’s talking about the leading civil rights icon of the 20th century. Young is up there too, when it comes to historical relevance. After serving as King’s top lieutenant, he became the first black man elected to Congress from the South since Reconstruction; he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as ambassador to the United Nations; he won two terms as mayor of Atlanta, and at 79 remains a tireless advocate of racial reconciliation and economic empowerment.

Young was in Washington earlier this year for the installation of his portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. Surrounded by family and friends and reflecting on those turbulent years when King and others risked their lives on a daily basis, he said with a wry smile, “When I think of the times I could have been hung in Mississippi and Alabama, it’s nice to be hung here in the National Portrait Gallery.”

He recalled how King would make light of the ever-present danger, telling the aides around him, “You all are so anxious to jump in front of me to take a bullet, I will preach you into heaven, so don’t worry.” King would then deliver mock eulogies that sounded more like a Richard Pryor or Eddie Murphy routine, Young said. “It was his way of making us laugh at our own death, but he was always aware his death was the most likely.”

Death was a daily conversation, Young said. “King’s house had been bombed, he’d been picketed and stabbed. The DeKalb County [Georgia] police had put him in the back of a van with chains on his hands and feet with a German Shepherd next to him, and drove him 300 miles on bad roads [to a maximum security prison]. Every time he rolled over, the dog growled.”

After a deranged woman stabbed King with a letter opener in New York in 1958, the surgery required to remove the letter opener from his chest left a mark like a sign of the cross. “He would say every morning, ‘I face the cross.’” Young recalled. After the Birmingham church bombing and President Kennedy’s assassination, King said, “If you can’t protect four little girls in Sunday school, and you can’t protect the president, whenever they want to take us out, they will.” King was a fatalist, resigned to whatever happened, telling aides he had no choice in how he would die, or when. “The only choice you have is what you die for”—words that he lived by, and that changed a nation.