One night in 2001, Matt McAllester stuffed garlic, prosciutto, giabatta, butter, and rosemary in between the skin and breast of a chicken, baked it so that the fats ran together, then served it to me. I brought a bottle of red wine made by Israelis who lived in a West Bank settlement where I’d been reporting that day—the story of two Israeli kids whose heads had been crushed by a rock by an Arab shepherd as they shared a picnic.

It was a fine meal. I remember it at least as clearly as the blood on the walls of the cave where the Israeli boys were murdered.

I worked in Jerusalem for Time and McAllester was Newsday’s Middle East correspondent. Together we covered the violence of the Palestinian intifada. At the same time, his mother Ann was approaching the end of a 20-year nightmare of alcohol and mental illness about which I remember McAllester spoke very little. It was always evident that there was some deep pain that ate at him, that made him run from his home in Scotland straight into every nasty conflict he could find, filling up the wound in his psyche with intense experiences of life and death. But then that’s not uncommon among war reporters.

It was always evident that there was some deep pain that ate at McAllester, that made him run from his home in Scotland straight into every nasty conflict he could find, filling up the wound in his psyche with intense experiences of life and death.

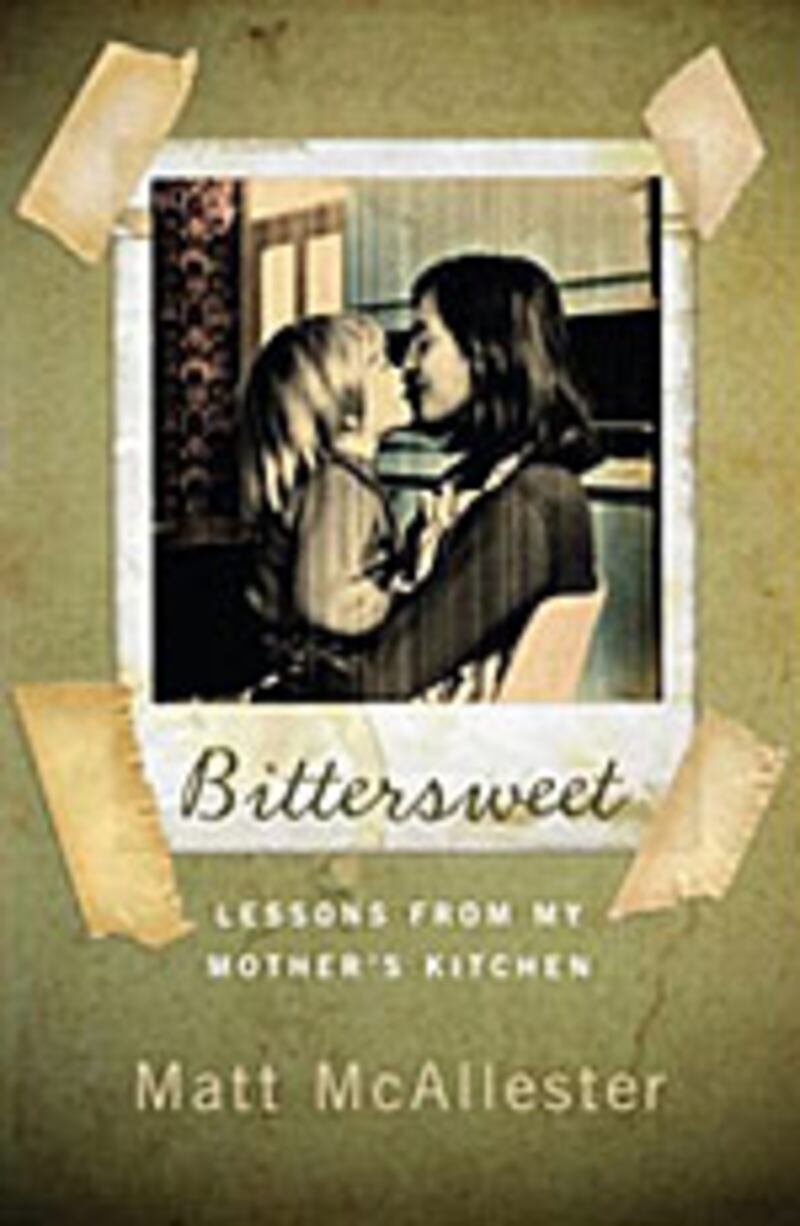

What is uncommon is McAllester’s response to his mother’s death in 2005. He didn’t look for more war in which to bury his grief. Instead, he turned to food, trawling Ann’s recipe books for tastes and sensations that would recreate the warmth and love he had felt from her before she went crazy. This quest is the subject of his powerful memoir, Bittersweet: Lessons From My Mother’s Kitchen (Dial Press).

“I needed to get my mother back,” explains McAllester in an interview with The Daily Beast. “There was no memorial that I could build other than one in words. I’m not much good at anything else. My mother wasn’t a famous person, she wasn’t a particularly nice person for much of her life, but she was my mom. I had to do the cooking and I had to do the book.”

The result is an examination of his relationship with his mother during his childhood idylls on the rugged Scottish coast, through the first flickering of mental instability as her marriage falls apart, into McAllester’s angry teenage years (“I wanted my mother, who had brought me into the world and deluged me with love, to die”) and on to the final years when Ann would disappear into the London night only to be discovered unconscious with drink on a sidewalk. In one wrenching episode, McAllester takes a break from the intifada to visit his mother in Ireland, but fails to recognize the puffy, tottering bag lady who greets him with happy tears at the airport.

McAllester, who has been based in London for five years and last month moved to New York, is one of the leading war correspondents of his generation. He’s won numerous awards for his work, first for Newsday and more recently as a contributing editor for Details. He sneaked past Serb militias into Kosovo for his first book Beyond the Mountains of the Damned (New York University Press) and was jailed in Abu Ghraib by Saddam Hussein’s secret police, an ordeal he recounted in Blinded by the Sunlight (Harper Collins). (The food in Abu Ghraib, incidentally, was most unhygienic. “My ass was just gone when I left there,” McAllester says.)

McAllester’s previous books are about the extreme situations war correspondents face. The format of foreign-affairs nonfiction dictates that, in those books, McAllester must present some kind of a solution, as though there was anything to be learned from war except that many people suffer for no reason, while other people are bastards and some of them get to really enjoy being that way.

Bittersweet is different. McAllester seems to suggest early in the book that everything’s going to turn out right. His mother may recover to enjoy her twilight years with her two children. His wife may become pregnant through IVF and somehow recreate his missing mother, naming the child Ann if it turns out to be a girl. Maybe that’s the book he’d have written if he was replicating the sob-story self-realization genre that populates daytime television. But McAllester has seen too many wars for that. He’s tricking us with hints of a comfortable ending, so he can hit us with the hard stuff.

When a foreign correspondent visits a war zone, he knows his stories won’t change the waste and suffering on the ground. He takes with him some colorful memories, probably also some traumas that will resurface in his dreams or in uncontrollable rages, sudden tears or boozing. And divorce, always, it seems, divorce.

The same thing, in a way, happens with McAllester and his mother’s cookbooks. The recipes turn into details which only obscure his feelings for her. He becomes a dictator in the kitchen. Every recipe must be followed with pinpoint accuracy, or else he discovers an anger rising in him at his loss of control. The taste of his mother’s food is almost like the traumatic memory of Saddam’s prison. He just has to let it go. (Click here for some of McAllester’s favorite recipes from his mother.) Forgiveness is the lesson of this harrowing, deeply honest book. That, McAllester notes, is what enabled his sister Jane to deal with their mother’s illness without the rage that engulfed McAllester, without running halfway around the world to avoid responsibility for a sick woman.

“I was incredibly angry at the imperfection of my own life,” he says. “It took 25 years before I understood what my sister instinctively saw—there are things that are simply outside our control. It’s best to accept that and to get on and try to make them better. I couldn’t accept it, so I just ran away. Jane’s never had that anger. She’s been involved in the reality of trying to make things better. Men could do with a little bit more acceptance of their own fallibility.”

Gender may, as he suggests, be a factor. But even female foreign correspondents can get rather macho, edging as close as possible to the gunfire and slugging back the whisky. Meanwhile, even in her madness, McAllester’s mother understood what it took him decades to figure out. Almost her last words to her son were, “If you need to keep the [recipe] book open, you’re not really cooking.”

A half-dozen wars showed McAllester the fallibility of other men, but it made him angrier at the world. Only when he faced his own failings could he forgive the way he ran from his mother.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Matt Beynon Rees is a former Jerusalem bureau chief for Time magazine, who has been based out of the Middle East since 1996. He is the author of Cain's Field: Faith, Fratricide, and Fear in the Middle East , a nonfiction account of Israeli and Palestinian society. He is also the author of the Omar Yussef series of Palestinian crime novels, including The Collaborator of Bethlehem and The Samaritan’s Secret, which was published in February.