“I think art breaks down otherness,” says Dee Rees, the filmmaker behind Mudbound, one of the finest Sundance movies in recent memory. “Art makes you see people as individual, unique human beings. Art, in that way, allows us to see each other in particulate, as opposed to in aggregate.”

Such is the beauty of Mudbound, a sprawling epic set on a flood-drenched farm in rural Mississippi—and the bloody battlefields of Germany during World War II—that earned a raucous standing ovation following its Sundance Film Festival premiere.

Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke) and his unfledged wife, Laura (Carey Mulligan), decamp from the city and, with their two young daughters in tow, settle on the aforementioned farm Henry purchased with the last of his money. Fortunately for them, the family of Hap (Rob Morgan) and Florence Jackson (Mary J. Blige) are sharecropping on the property, and able to assist the overwhelmed and underprepared white couple with the day-to-day struggles of range life. Unfortunately for everyone, the McAllans are joined by Henry’s elderly father, Pappy (Jonathan Banks), a repulsively racist southerner who believes in enforcing white supremacy by any means necessary.

“Everybody’s fighting their own battles at home,” offers Rees. “So with Hap, you see how a broken leg and a dead mule can change the trajectory of their well-being; for Laura, you see how a miscarriage changes the trajectory of her marriage. Each family suffers privately, and by being in each family’s private joy and private suffering, we give context to this time.”

Thousands of miles away, there is Jamie McAllan (Garrett Hedlund), Henry’s striking, romantic younger brother, who’s overseas flying bombers for the Allied Forces against Nazi Germany, and Ronsel Jackson (Jason Mitchell), the Jacksons’ eldest, a sergeant in the 761st Tank Battalion—a group comprised of mostly African-American soldiers, dubbed “The Black Panthers”—stationed in Germany under the direction of General Patton. When Jamie and Ronsel return home to the Mississippi farm from the war, they strike up an unlikely friendship, bonding over their shared sense of loss, but their beautiful union soon threatens the grange’s racial imbalance.

And Ronsel, who found love and acceptance with a stunning white European woman while stationed abroad, returns home from fighting for his country to find that little has changed.

“Ronsel is more an American overseas than he is in Mississippi,” says Rees. “I have to give credit to Virgil Williams and the script, because in what World War II film do you have the Red Tails and the Black Panthers in the same story? I love seeing all these men fighting, and speaking generally, I feel like the military and sports are the institutions that have done the most for integration in this country because they’re institutions which place people in proximity to each other, and proximity under duress is what breaks down this idea of us vs. them otherness.”

Rees, 40, knows a thing or two about overcoming “otherness.” She is an openly gay black woman from Tennessee who tells stories that others ignore, and who’s risen up the Hollywood ladder through grit, determination, and a whole lot of skill.

“On both sides, if everyone tells their own narrative, then things get told more truthfully,” she says. “The more everybody can be specific, I think the more interesting the stories become.”

After graduating with an MBA from Florida A&M University, Rees worked in brand management for a bunch of corporations, including Procter & Gamble, before enrolling in New York University’s film school. Her master’s thesis was a 40-minute version of what would eventually become her debut feature, Pariah, and she later fine-tuned it in the Sundance filmmaking lab. When Pariah, an achingly personal tale of a 17-year-old young black woman embracing her lesbianness, premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival it received raves, and was quickly snatched up by Focus Features. Rees’s sophomore feature, Bessie, chronicling the life of legendary blues crooner Bessie Smith, dropped on HBO in 2015, and went on to receive four Emmy Awards—including Outstanding Television Movie.

But Mudbound is something else entirely—a grand old Hollywood production brimming with scene after scene of chaos and lyrical splendor, which immediately places Rees in the upper echelon of directors.

Virgil Williams’s script for Mudbound, adapted from Hillary Jordan’s novel of the same name, was brought to Rees’s attention by producer Cassian Elwes (The Butler) in early 2015. She read the screenplay and then went back and read Jordan’s book, tweaking it to include its multiple narrators and plethora of internal monologues. It paid off immensely. One of the film’s finest attributes is its richness of perspective, splitting screen time and narration duties equally between its six central characters: the three McAllans and the three Jacksons.

“Getting into these characters, I wanted to be completely subjective,” says Rees. “So when you’re with Henry, you see the field the way Henry sees it, with this romanticized view of what he’s doing; when you’re with Hap, you see the field as Hap sees it, which is this idea of never being vested—what it’s like to work, to work, to work and never be vested.” “This idea of everybody fighting on their own front lines I kept coming back to,” she continues. “The women, Florence and Laura, are each on the front lines of their family and in a lot of ways they’re the first face of their family to the other side. I also wanted to explore the idea of whiteness as currency, so all the characters have it, it’s just how they spend it: Pappy flaunts his, Henry spends his firmly, Laura bargains with hers, and Jamie tries to burn his.”

According to Rees, the film was shot last summer in just 27 days—which is very hard to believe given its high production values, replete with World War II tank battles and dogfighting.

“We lost two days to rain, shot two days for the war stuff in Budapest, and one day in Long Island for the airplane stuff. So it was 30 days or 31 days all-in,” she says with a grin, amazed that she’d managed to pull it off. “I really had to count on my cast. They were in the muck, there was no time to go back to their trailers, and it was hot, sticky, and uncomfortable, but I think staying in that discomfort allowed us to create this thing.”

She laughs. “When we went to Budapest to do the tank battle, we literally shot that tank battle scene before lunch. It was insane. Then we had lunch, and then we went off to shoot the European village scene. To be able to do that was crazy. Shooting a tank battle before lunch, to me, was the biggest triumph of the making of the film. We should get T-shirts made that say, ‘We shot a tank battle before lunch!’”

Both Ronsel, a tank sergeant in the Black Panthers, and Jamie, a bomber pilot flying missions over Germany, barely escape death. When they return from the war, they’re haunted by memories of it, with Jamie drowning his demons in booze and Ronsel hoping to one day return to Europe, where he’s treated like a human being; they feel like aliens in their own land.

Ronsel’s story was a personal one for Rees.

“I realized all of the questions I never asked my grandfathers,” she says of making the film. “Both grandfathers fought in different wars. My mother’s father fought in World War II, and then my father’s father fought in Korea. And they’re both these country boys, one from rural Tennessee and one from rural Louisiana—and they never went back home. My father’s father was from Fayetteville, Tennessee, went off to Korea, and then moved to Nashville, which to him was the big city. My mother’s father was from Ringgold, Louisiana, and then they ended up moving to Oakland, California. So thematically in this film I wanted to explore the impossibility of going back home.”

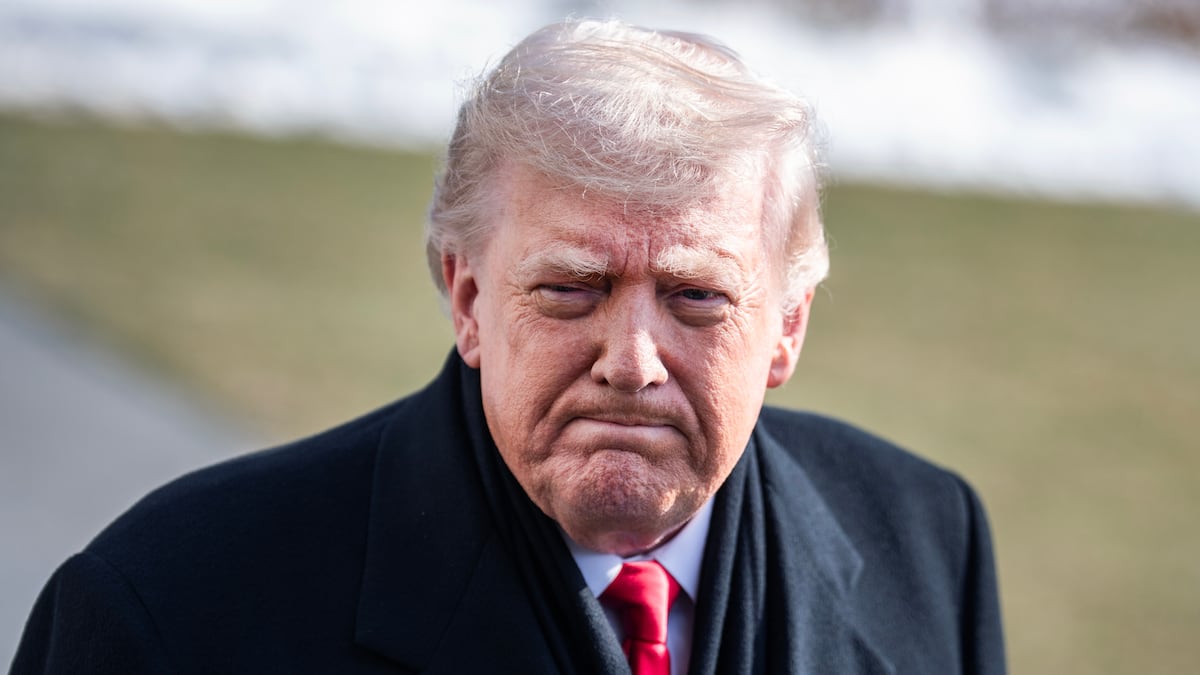

There is also the specter of the Ku Klux Klan looming large over the proceedings. And Rees, like most Americans, found it troubling that a seemingly archaic, hateful organization like the KKK could still be making headlines in 2016—as they did when their official newspaper endorsed Donald Trump, whose father was mysteriously arrested during a Klan riot in Queens, for president.

“It’s still alive,” says Rees, shaking her head. “Another big theme of the film was the idea of burial. Pappy, in a way, represents history. So are you going to bury your history and not deal with it and pretend it didn’t happen—and then it will continue happening—or are you going to put it to rest? Just like I have grandparents that I know were sharecroppers, somebody has grandparents that were slave owners. So we need to be specific and say, ‘Yes, my grandfather did that, yes, my grandmother did this,’ and own it, and only then can we break through.”

The sound mix for Mudbound was finished just a week before its Sundance premiere, which as luck would have it, fell on the same day as the women’s marches across the world protesting President Trump.

“I keep going back to this idea of fighting on multiple fronts, and for us, my wife and I had marched on Inauguration Day in D.C., January 20th,” shares Rees. “We felt it important to be visible, to be vocal, to not buy into a peaceful transition narrative, and to say what’s true. It was great to protest in D.C. on Inauguration Day and then fly to Sundance the next day and this film is like fighting another front, in a way. Culture—art, music, literature—is the long game, because it’s the way to change people’s ideas in a more personal way.”