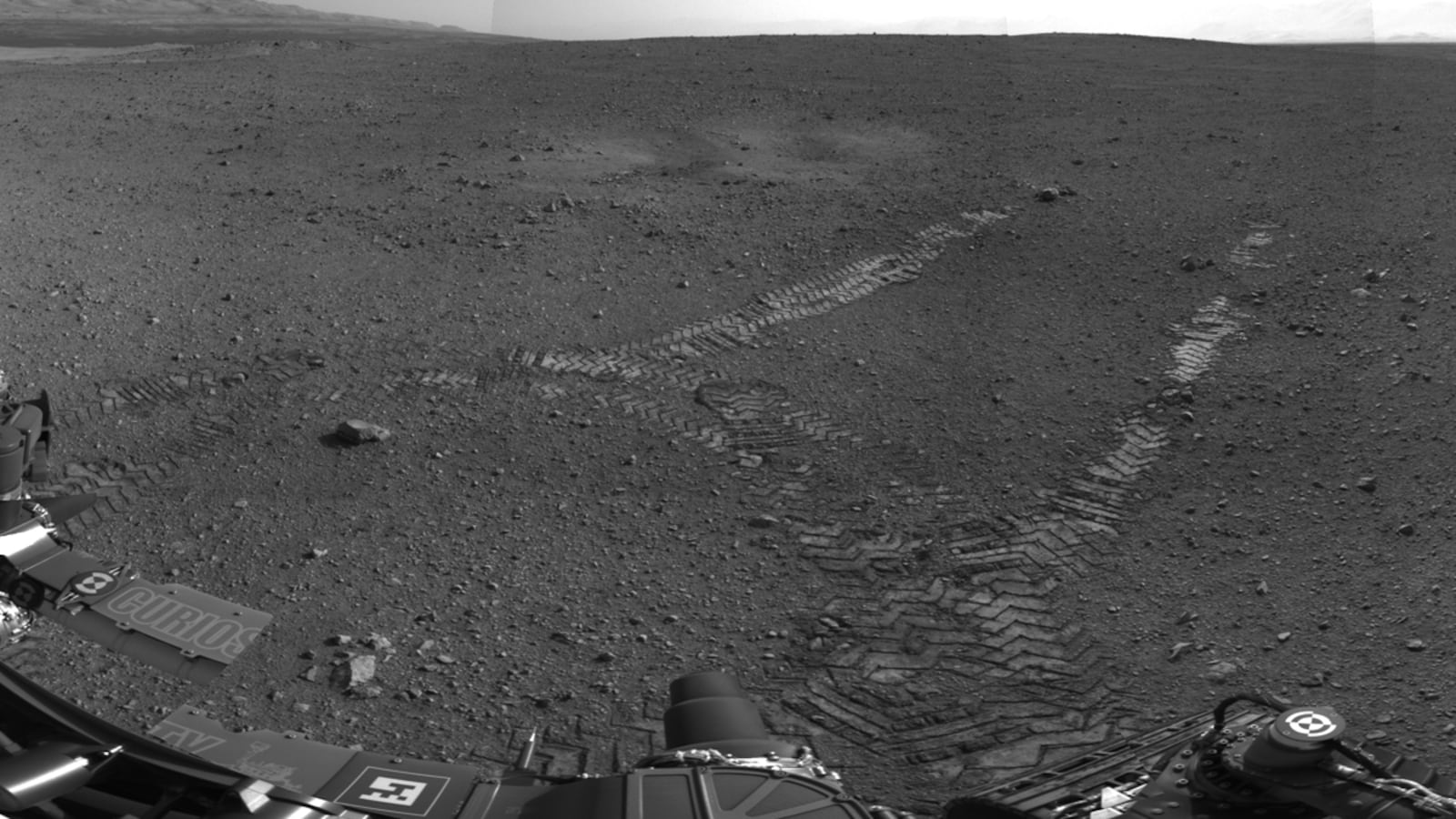

When the Curiosity took its first drive on Mars last week, NASA broke the news not in a press release but through the robot’s insouciant Twitter account. “This is how I roll: forward 3 meters, 90º turn, then back,” tweeted the bot, before inviting its million-plus followers to do the electric slide.

That’s a lot of followers—not quite the 53 million who tuned in to watch Neil Armstrong’s small step, but nonetheless an impressive fan club for an agency that has had its budget slashed, its shuttle program mothballed, and whose best days were supposed to be behind it. And NASA’s followers are active—tweeting, participating in Q&As with engineers, and watching frequent livestreams. They’re also watching celebrity fans—Ryan Seacrest, Britney Spears, and Steve Martin have all conversed with the bot—which, of course, broadens the rover’s reach.

Part of Curiosity’s appeal is its spunky voice and facility with nerd culture and Internet memes. It’s a direct descendant of Phoenix Rover, which was signed up for Twitter back in 2008. The Phoenix was scheduled to land on Memorial Day weekend, and an enterprising NASA social-media specialist named Veronica McGregor needed a way to get the news to the millions who wouldn’t be in front of their TVs. After a few test tweets, she adopted the first person to save space, and the response was overwhelming. By the time Phoenix tweeted “We have ICE!!!!! Yes, ICE, *WATER ICE* on Mars! w00t!!! Best day ever!!” it was the fifth-most-followed account on Twitter.

“We went, wow, here’s this amazing audience and they’re really craving what we do,” says McGregor. It turned out not to be a passing fancy. Some 3.2 million people streamed this month’s Mars landing, three times as many as streamed Michael Phelps’s victory in the 200m medley. Engineers now field questions on Reddit and laboratories raffle off multiday tours to Twitter followers. Many of the questions they get are from people asking what they have to study to become NASA engineers like the ones seen in Twitpics of mission control, some of whom, like the young guy with a star-spangled mohawk, have recently become Internet celebrities themselves.

“This generation, 18-35, they are interested in science,” says Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium and frequent interlocutor with the rover. “The problem is adults aren’t interested.” The data seem to bear this out. According to a 2009 Gallup poll, Americans too young to remember the moon landing are more likely than older people to say the space program’s benefits justify its costs.

“When I started at NASA we used to say we’d know we’d done something with our lives if we converted one student to studying math and engineering,” says McGregor. “Now I look back and say, We were happy with one? I look at this and say I hope we’re igniting that spark in thousands.”