Early Monday evening at Columbia University’s main campus, a grad student in a white lab coat stood outside Havermayer Hall, holding a cardboard sign. “Will analyze data for tickets,” it said.

His odds were long and getting longer, as throngs of people began streaming into the old-fashioned lecture hall for the evening’s strangely high-profile event.

Eric Kandel was there.

The room was packed, sold out weeks ago, for the night's event, organized by a group called Neuwrite—science writers and writing scientists affiliated with the university.

Everyone had come to hear two hot-shot neuroscientists, Sebastian Seung and Tony Movshon, debate how best their field should proceed. It was the kind of argument that today typifies neuroscience—a field so much still in process, a scientific community in hot pursuit of the last great human unknown.

Robert Krulwich, the host of NPR’s edgy science show, Radiolab, was there to moderate.

He set out the evening’s central questions.

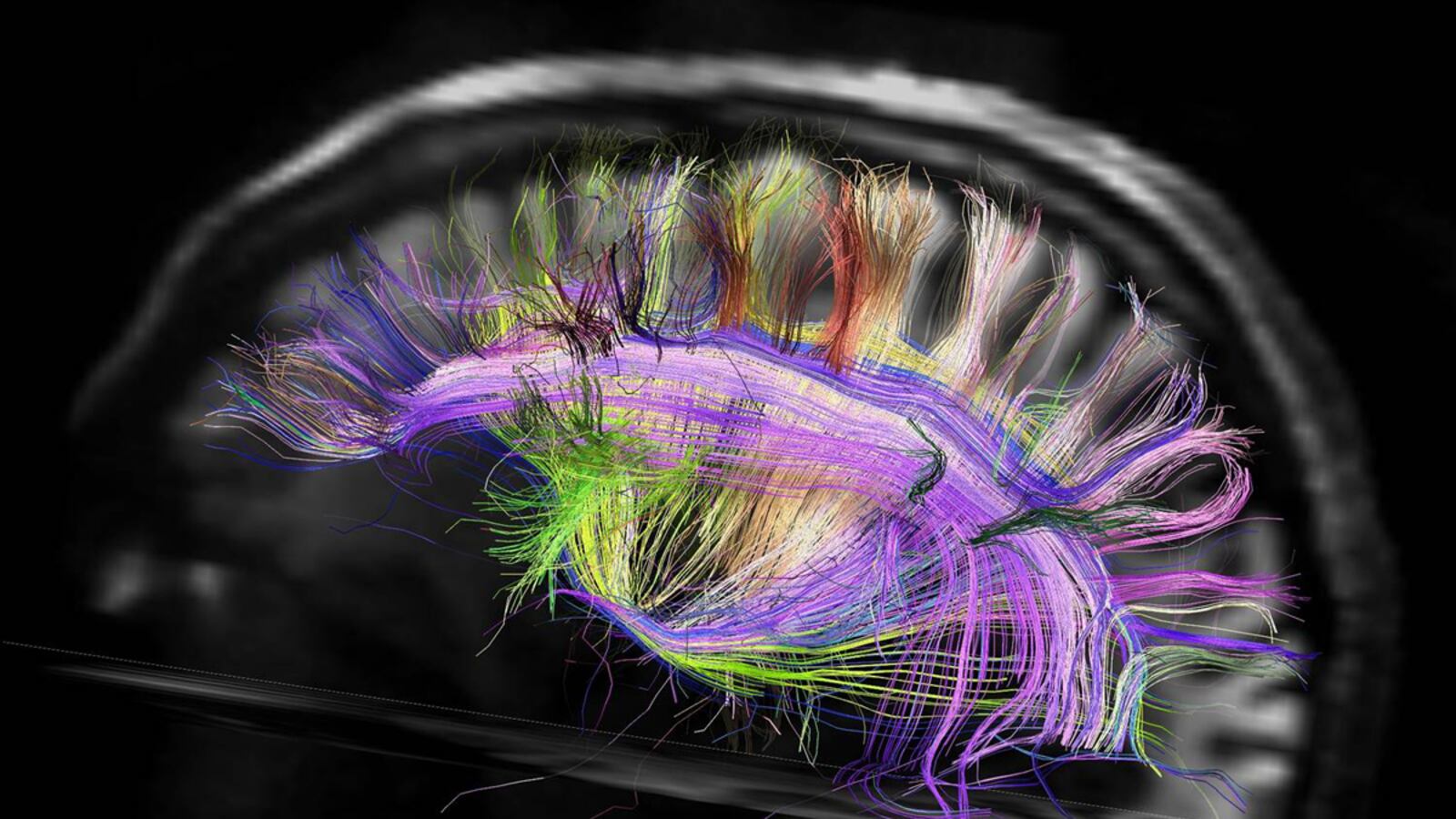

“Do we need to create a map that will eventually describe every neuron in our head—or don’t we?” he asked. “And the deeper question underlying that is, does the brain’s wiring really make us who we are?”

The contenders took their seats. First came Sebastian Seung, this season’s whiz kid. Professor of computational neuroscience at MIT and the author of the new book Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are. Charismatic and youthful, Seung was wearing shiny gold sneakers and a blazer with metal studs on the back.

His opponent, Tony Movshon, older, stouter, and, it must be said, considerably less indefatigable, was out-flashed. It proved to be the theme of the night.

Movshon is a respected scientist and the director of the Center for Neural Science at NYU. But Seung has a grand vision for the field. He’s a reformer on a mission.

In his new book, Connectome, Seung argues that the crucial next step for neuroscience research is to find a way to map the intricate connections between every neuron in individual human brains. The pattern of connections between neurons, more than the neurons themselves, Seung says, is the basis for understanding human mental functions. Our “connectomes”—patterns of wiring—provide the crucial insight that can advance the field forward.

Take, for example, psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and autism. These are brain disorders, yet the brain cells involved look, for the most part, normal. They look healthy. Many researchers have now come to believe that the disorders do not arise from abnormal neurons, but rather, abnormal patterns of connections between them.

To figure out these connections requires much more sophisticated research technology than currently in existence. But mapping the so-called connectome, Seung says, “would provide information that’s been missing and hindering the progress of neuroscience for a very long time.”

After all, for all its sensationalized, media-friendly doings, neuroscience isn’t yet turning up the grand revelations about the workings of the human mind that many expect to see. Despite the endless books and newspaper inches devoted to this scientific field, we still find ourselves without answers to such seemingly basic questions as, what causes depression?

Or, for that matter, “Why have we not managed to figure out exactly how memory works?” as Seung put it Monday night.

Seung believes that neuroscience has gotten stuck.

“I want to understand the brain,” he said. “Well, people don’t even agree on what that means.”

Movshon, representing the opposing side, was not arguing that Seung is wrong, necessarily. He was not saying that Seung’s obsessive focus on the connectome won’t, ultimately, yield valuable information.

“Like any rational scientist, I’m not going to argue against the acquisition of knowledge,” Movshon began.

But the problem is that the world is not infinite. There’s limited time and money to put toward any research endeavor, and “the connectome alone only tells you what might happen,” Movshon said. “Not what will happen.”

One of the fundamental points of disagreement between Movshon and Seung is, as they themselves put it, the question of grandeur.

“The problem of grandeur in neuroscience is one I think we’re all concerned about these days,” Movshon said. “The idea that we have to have a grand plan for a grand problem to make grand progress ... It’s very seductive.”

But the impulse toward grandeur is dangerous too, Movshon believes.

or him, neuroscience is and should remain “a cottage industry,” one in which neuroscientists tackle specific, local regions of the brain until, eventually, everyone understands his or her specialized region inside and out, and a better, more sophisticated picture of the brain as a whole emerges from the different pieces.

And here is the fault line laid bare. Many in the field are wondering—and some attempting to answer—is it better to stay the course, plodding along with highly focused, localized experiments, studying, for instance, every tremor of a single group of neurons in one tiny corner of the mouse brain? Or should neuroscientists be thinking bigger—flashier—to the grand scheme, the eggs-in-one-basket approach?

There are a few such grand schemers out there already.

The most notorious, perhaps, is Henry Markham, the grand schemer behind the Blue Brain Project, the ultra-ambitious attempt to simulate the entire human brain within one decade. The Blue Brain team is currently in year two.

There was a moment of testiness Monday night, when Movshon invoked Markham’s name, drawing a comparison to Seung and the grandeur of his own connectome project.

The testiness reflects an ambivalence in the field about what Markham and the Blue Brain team are trying to do. No one’s sure how to feel about it. Is it bravura, some egotist’s wild goose chase? Or might it actually work? Many hesitate to take a position.

The debate wound down.

“I’m sure I said some things that got up Sebastian’s nose,” Movshon said, in a conciliatory way.

But not far enough up Sebastian’s nose for Krulwich, who bemoaned the lack of “blood on the floor,” and then graciously thanked us all for coming.