When the eighth issue of Jasad—a Beirut-based cutting edge art magazine—rolls out next month, it will be the face of criticism and denouncement throughout the Middle East. Betwa Sharma on why the publication continues to succeed.

“They think they own my freedom/I let them think so/And I happen,” writes Joumana Haddad, in one of her poems called I Am a Woman. Two years ago, Haddad made “happen” Jasad, an audacious magazine in the Middle East devoted exclusively to the body.

Even as conservative factions of Islam have choked the liberal stream of ideas that existed in the region even two decades ago, some women doggedly claim a right to their bodies and sexuality; Jasad is perhaps a manifestation of that claim.

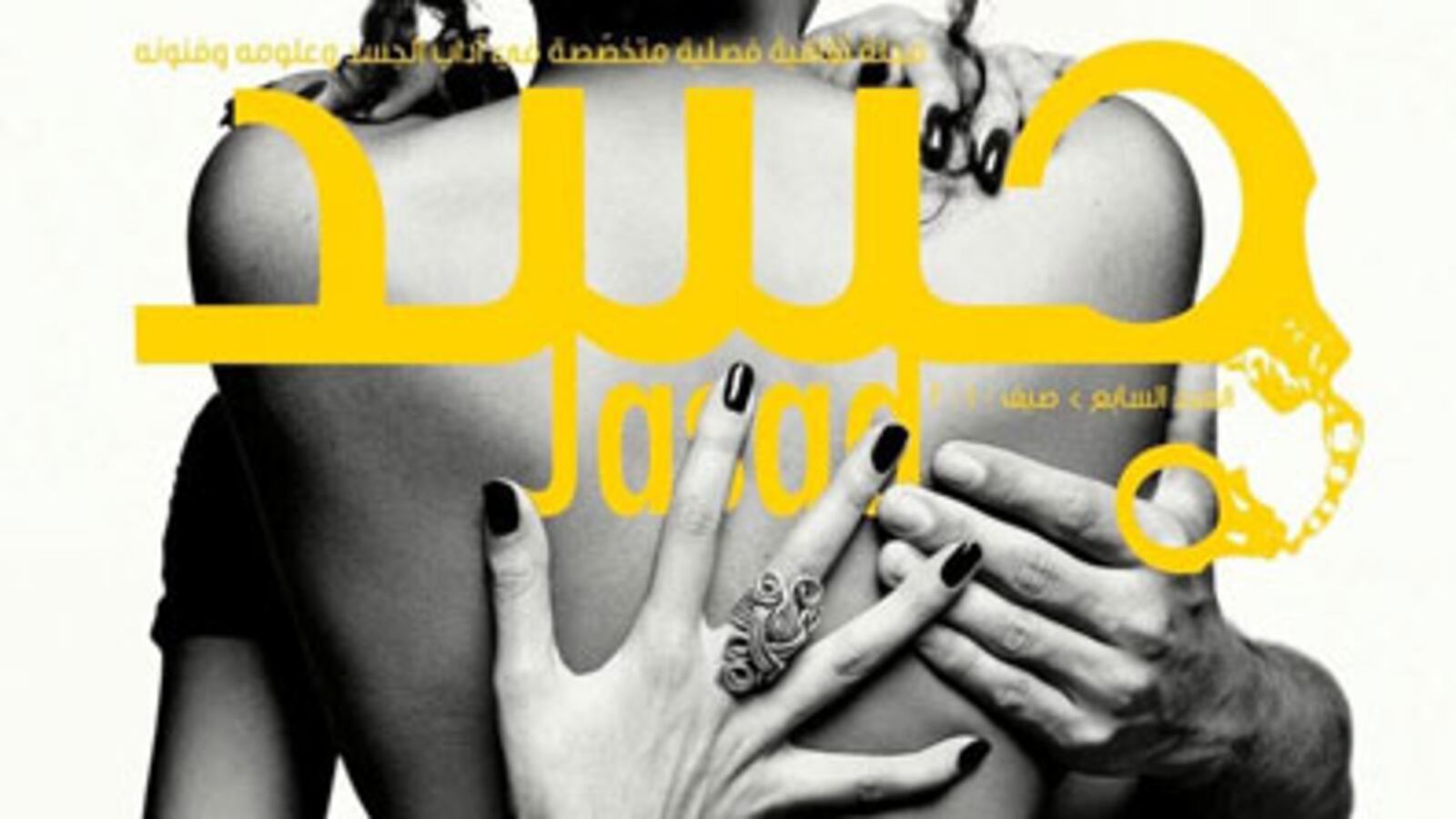

A peek through the keyhole on its website reveals a moving line of classic and contemporary nude images. The busted handcuff, which dangles at the beginning of Jasad’s spelling in Arabic, symbolizes a break from veiling the body.

“Have you ever seen a man in a burqa?” said Haddad, founder and editor-in-chief of the magazine, which is published from Lebanon. “It is an act of violence and oppression practiced exclusively on the female element of society.”

Haddad, a 40-year-old poet from a Catholic background based in Beirut, wants Jasad to be a place where Arab artists and writers have the “freedom to disobey.” But the editor, who describes herself as an agnostic, insists the magazine, which contains articles on erotica and homosexuality as well food and cinema, isn’t just to provoke.

“I like to believe in the healthy impact that comes after the initial, rather superficial shock” of reading it, she said. “It a serious cultural reflection on one of this region’s main problems. Expressing is part of the healing process.”

The eighth edition of the magazine debuts in October, and its circulation all over the region has been steadily increasing. (The most subscriptions in the Middle East come from UAE, Bahrain, Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.)

Within Lebanon, the magazine is distributed to bookshops in sealed bags. There has been no censorship yet, but hate mail still persists, according to Haddad, including a recent rape threat. “You get used to it. I’ve never expected unanimity over Jasad,” she said. “But this magazine wouldn’t have been possible in any other Arab country.”

Gallery: Jasad Magazine

Yet the editor is not without critics who find her being disingenuous about the kind of restrictions she faces, especially in a relatively open society like Lebanon.

“Lebanon has become quite hospitable in recent years to various forms of sleazy and pornographic publications,” writes As'ad AbuKhalil, a prominent Lebanese American professor at California State University, Stanislaus, on his blog, The Angry Arab News Service. “So no one is oppressing her if they know who she is.”

Hassad’s contents, if provocative, are hardly meant to be “sleazy,” but the rules of what gets someone into trouble vary widely in the Middle East. While an artist could be on tenterhooks in Saudi Arabia, there is more room for creative maneuvering in countries like Jordan and Lebanon.

Ali Maher, the former director of Jordan’s premier art institution, Darat al Funun, explained that despite a blanket of fundamentalism, many artists are painting nudes and erotic art in the region. Much of this work is displayed in private galleries for small audiences. The pieces are bought and sold directly between the artists or their agents, according to Maher. “Believe me,” he said, “Some of this ends up in bedrooms of Saudi Arabia.”

In his current project called “Nude Amman,” Maher is working with nude models to mock the elite of Jordan’s capital. “Every artist has the desire to paint the body,” he said, “but you need a strong heart to stand up to extremists.”

On the other hand, Nada Shabout, a professor of Islamic art at the University of North Texas, asserted that cases like Maher in the Middle East are the exception and not the rule, not only due to the rise in religiosity but also because Arab artists have other preoccupations.

“It’s unfair to compare… Why should artists in the Middle East do what the West does?” she said. “One culture wants clothes off, the other prefers them on…What good will it do the world if women in the Middle East take their clothes off?”

Shabout, however, explained that a lack of skin didn’t mean that the Middle East was any less sexual than the West. “There are extreme contradictions between what the culture shows and what the religion demands,” she said.

Girls of Riyadh, for instance, was a bestselling chick-lit in the Middle East about four girls in Saudi Arabia searching for love. Its young author, Rajaa al-Sanea, received death threats for the 2007 novel, which was banned in her home country.

Another artist from Saudi Arabia, Hend al-Mansour, left the country in 1997 to continue painting the body. But even in the United States, she finds herself being occasionally censored.

In Al Badr, meaning “full moon,” al-Mansour painted a man falling into the embrace of God, who is depicted as a naked woman. “Mohammad is the seeker and the woman is the giver of knowledge and everything else,” she said, alluding to the Prophet’s respect for women.

“Every artist has the desire to paint the body, but you need a strong heart to stand up to extremists.”

But not everyone agreed, and al-Mansour couldn’t exhibit her work in the U.S. after she finished it two years ago. The 44-year-old painter is hoping that her next exhibition, which is a narrative on the women of Saudi Arabia, will show without too much trouble. Fatimah, on display starting October 8 at Montana State University in Billings, is a sculpture of a woman prostrated while praying in a room created to look like Saudi Arabia.

The sculpture, which al-Mansour modeled on herself, is designed to be glitzy, garish and covered only with a translucent shawl. “The woman of Saudi Arabia today is a combination of spirituality, sexuality and materialism,” she said. “The sexuality is hidden but never gone.”

For Arab women, however, warding off fundamentalists is only half the battle. The existing stereotypes about them brandished by the West can be equally suffocating. In her new book, “ I Killed Scheherazade, Confessions of an Angry Arab Woman,” Haddad attacks some of the clichés, the biggest one being the “oppressed, veiled, victimized woman.”

The book also gives an insight into what led the author to create an erotic magazine and the rules that it operates by. All the writers and artists, for instance, publish under their real names; pseudonyms are not accepted. A paper publication was deliberately chosen to challenge the censorship even more. “A digital version would have been easier,” said Haddad. “I chose difficult.”

To her critics, Haddad echoes the sentiments of the German poet, Novalis, who wrote “There is but one Temple in the World; and that is the Body of Man. Nothing is holier than this high form.”

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Betwa Sharma is the New York/United Nations correspondent for the Press Trust of India and an AOL News Contributor. Her freelance work has appeared in several outlets including The Huffington Post, The Global Post, Time.com, Indian Express, Hindustan Times and Columbia Journalism Review.