I am a member of one of America’s larger and still very active 9/11 interest groups. I wrote a book about it.

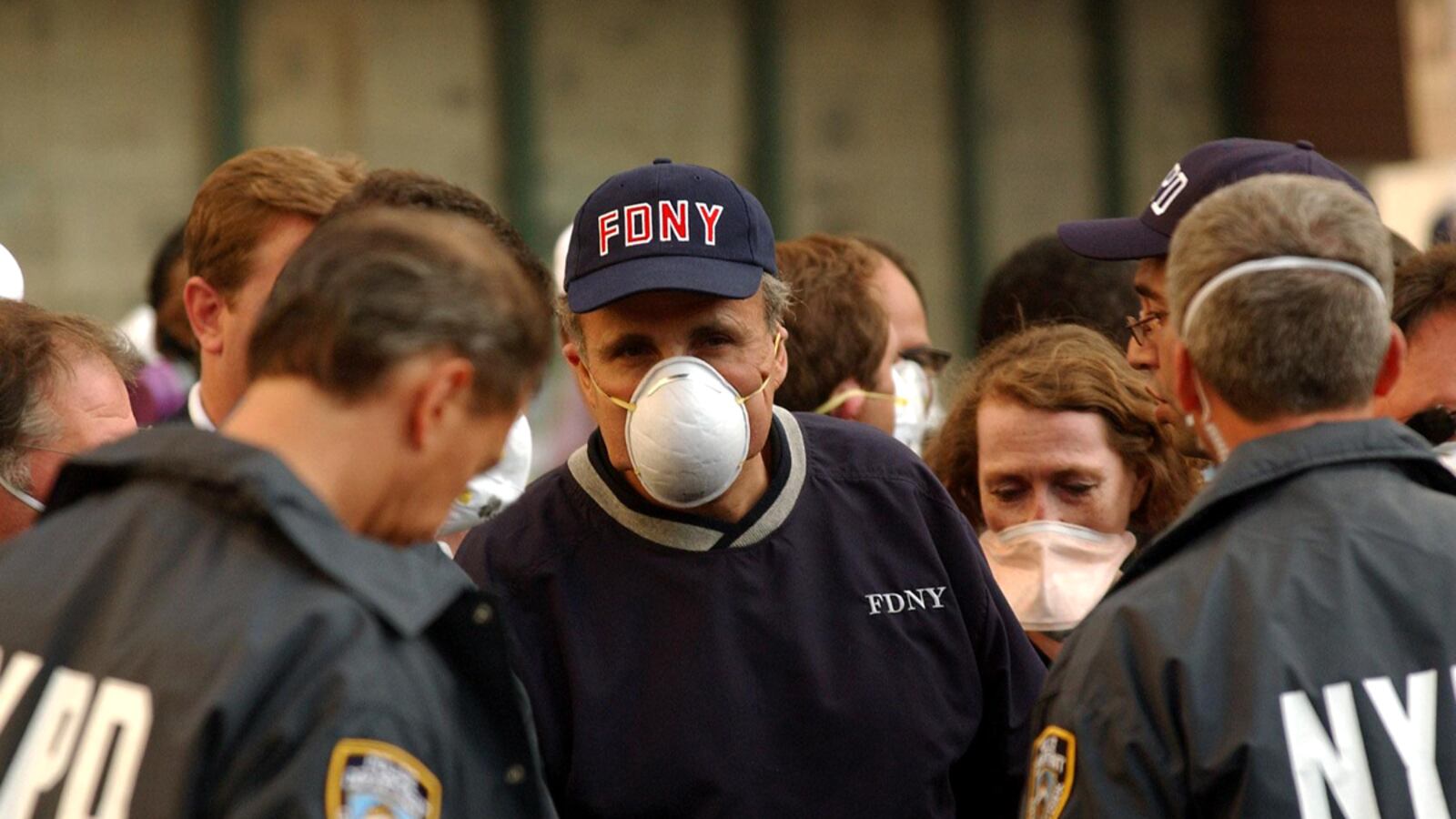

Called Grand Illusion: The Untold Story of Rudy Giuliani and 9/11, it started out as something quite different. My coauthor, Dan Collins, and I sold HarperCollins in 2002 on a book about Rudy and four other pivotal, New York, 9/11 figures, but it wound up becoming my second Giuliani book by default. We thought that by 2004 or 2005, there would be a rebirth story at Ground Zero to tell, but as we approached the due date, zero had happened at Ground Zero. Some of our other original subjects, especially the Kings of the Promised Comeback, Gov. George Pataki and developer Larry Silverstein, also zeroed out. Meanwhile, Rudy, knighted for 9/11 valor by the queen and Time, was, according to the early polls, on his way from the Towers to the White House.

So we did a book that was begging to be done. Larger than Rudy, it is a catalog of everything that went wrong in the city’s preparation between the two attacks on the World Trade Center, and all the screw-ups in the response that day. I am happy to report, in the Tina Brown spirit of Newsweek’s cover this week, that the city under Mike Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, and Office of Emergency Management Director Joe Bruno has been quite “resilient” in the effort to make New York safer, in stark contrast with Giuliani’s shockingly indifferent response to the less deadly warning shot of 1993, the very year he was elected mayor.

You may notice an omission on the list of vigilant New York officials. As effective as Bloomberg has been at OEM and the NYPD, he has never taken on the challenge of reform required at the FDNY, instead installing at its current helm, for example, a department functionary already faulted by former Manhattan district attorney Robert Morgenthau for his mismangement role in the lead-up to the worst fire debacle of the Bloomberg administration, the 2007 scorching of the Deutsch Bank building next to Ground Zero, which cost the lives of two valiant firefighters marching six years later in the footsteps of their fallen 9/11 brothers.

One mark of Giuliani’s wilfull ignorance of the terrorist threat was that the number of NYPD detectives assigned to the Joint Terrorism Task Force was the same on 9/11 as it was on the day of the first bombing almost nine years earlier—a mere 16 or 17. That was in a department swollen by 5,000 additional cops hired in the Giuliani era. In a department cut by 6,000 under Bloomberg, more than 100 detectives are assigned to the task force, and they are a small part of the counterterrorism army Ray Kelly has deployed here and around the world. John Lehman, the former Navy secretary under Ronald Reagan who was the 9/11 Commission member most critical of the Giuliani preparation and response, told me that Kelly’s counterterrorism force “is probably the best in the world,” adding “if I was president, I would be regularly briefed by Kelly’s unit.”

Lehman drove New York’s Giuliani-fawning tabloids nuts at a 2003 commission hearing when he took on the NYPD commissioner Kelly replaced, currently jailed felon Bernie Kerik, and Giuliani’s fire and OEM commissioners, all three of whom were then working at Giuliani Partners, the marketing arm of Rudy’s 9/11 legend. “It’s not worthy of the Boy Scouts, let alone this great city,” said Lehman at the New School hearing, referring to the “command and control and communications” breakdowns on 9/11.

Like the other commission members, Lehman is now part of the National Security Preparedness Group, which issued its nine-point report card this September, isolating the most vital of the 41 commission recommendations that remain “unfinished.” Ironically, the first two on this list of continuing “vulnerabilities” are precisely the ones that Lehman referred to at that hearing: “command and control and communications.” The preparedness group’s brief report surveys our national failings, without any specific reference to New York, the once and future prime target. The report’s assiduously apolitical analysis of our inability to make real progress on the communication issue points a finger at no one in particular. But President Obama is pushing a bill that would provide a dedicated radio spectrum to public-safety agencies that literally every major law-enforcement or fire organization in the country supports and that won 21 to 4 bipartisan support in a Senate committee in June. Why has it gone nowhere so far?

Chuck Dowd, the NYPD’s top communications expert, appeared on Fox News recently and blamed the gridlock “quite frankly” on “some Republicans in the House,” despite support for the bill from Homeland Security Committee chair and New York Republican Peter King. Oregon Republican Greg Walden, the chair of the House’s Energy and Communications Subcommittee, wants to sell the spectrum to Nextel, Verizon, and other hungry commercial buyers, arguing that public safety has enough spectrum now. As the House dawdles, the recent earthquake and hurricane proved once again that cellphones cannot be counted on in a crisis. Bloomberg is pushing the Jay Rockefeller–Kay Bailey Hutchison bill, and Kelly testified for it at a Washington hearing, contending that “a 16-year-old with a smartphone has a more advanced communication capacity than a police officer carrying a radio.”

Despite the failure to address the national interoperability issue, as this inter-departmental sound of silence is called, the Bloomberg administration appears to have made some progress. It has at least put into place several new ways that the FDNY and NYPD can talk to each other, though neither Deputy Mayor Cas Holloway nor a police deputy commissioner could tell me how often these new radio options are actually used by two departments that famously love to hate each other. The police have a new frequency, TAC-U, that the FDNY can access, at least theoretically. The FDNY’s commissioner also boasted at one FCC appearance that the department has given 200 dedicated interoperable radios to department chiefs, but OEM handed out other interoperable radios to FDNY brass prior to 9/11, and even the chief of the department left his in his car the day of the attacks. No one ever used them, before or on 9/11.

Of course, the breakdown that hangs in everyone’s collective memory about 9/11 is the warning of impending collapse from police helicopters that no firefighters ever heard because the departments operated inside radio silos. New protocols put fire chiefs aboard police helicopters, but again, that’s theoretical since the choppers would have to wait at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn for the fire chief to arrive. The FDNY still has no helicopters of its own. The interoperability avenues available to FDNY field-communication units and at other leadership levels make it likely, however, that this kind of deadly autonomy will not recur.

Command and control, says Lehman—who called Giuliani’s ambiguous executive order on the subject “a scandal” at the 2003 hearing—has gone from chaos to “clear lines of authority.” Lehman says he would give the Bloomberg administration an “A” for “finally cutting the knot” and putting the cops in charge at most crisis scenes. “On paper, it’s resolved,” he says. “I don’t know if that’s how it’s actually functioning.” Peter Vallone, the longtime chair of the city council’s public-safety committee, says he’s scheduled hearings on precisely these two issues, unified command and communications, for Sept. 27, adding that he tried to hold the hearings the week before 9/11, but the Bloomberg administration balked. “A lot has been done and more needs to be done” on both fronts, says Vallone.

The greatest pushback came when Bloomberg put the new incident command system in place a few years ago and assigned hazmat incidents to the police, making New York the only major city where the police department is schematically in charge of hazardous-material incidents. “The FDNY didn’t agree, but it has been working real well,” says Vallone, though fire officials have complained that its highly skilled hazmat unit was once held at bay by police for 90 minutes when a truck tanker leaking potentially hazardous material crashed on a Bronx highway. “There are always going to be rivalries out on the street between agencies, but I think there are less now than there ever was because of this system,” concludes Vallone, who is closely tied to both departments and their unions. But, added one top city official who doesn’t work for Bloomberg: “Whenever there are different commissioners on the scene, it doesn’t matter what any manual says. Ray Kelly is in charge, and thank God that he is.”

Vallone also says OEM has “grown,” as does its founder, Jerry Hauer, Giuliani’s first commissioner, who left years before 9/11 to take a top emergency-response job in Washington. Hauer is skeptical about how real both the command and communications improvements are on the ground. “There is not true interoperability now,” he says. “It’s the culture of the two agencies that they just don’t talk to each other on the radio. I’ve talked to many people involved now, and they say there is no communication going on.” He believes Bloomberg “doesn’t have the courage to stand up to Kelly,” and that he’s ceded authority to him on hazmat and other incidents that Kelly should not have. Hauer, who runs his own consulting firm, says that at crane collapses and other incidents, “two separate operations have gone on,” with police and fire still functioning separately, an observation that Deputy Mayor Holloway stoutly denies. Holloway concedes that each department still has a “unique culture” that can produce friction, but insists the progress is real.

Wayne Barrett is a Newsweek/Daily Beast contributor and a Nation Institute fellow who is the author of several books, including Grand Illusion and Rudy! An Investigative Biography. Research assistance was provided by Emily Atkin, Matthew DeLuca, Kelly Knaub, Fausto Giovanny Pinto, and Andy Ross.