We’re mere months into the new year and the sophomore run of the current administration, and all of us have aged twice that amount. We could use a boon; we certainly need a reprieve. A movie about a unicorn, that symbol of hope and grace from European antiquity, seems like just the ticket, right? What better creature to relieve us, even if temporarily, of our dread and our anxiety in these dreadful, anxious times? As a bonus, Jenna Ortega co-stars with Paul Rudd! Score. Next stop: bliss.

There’s one problem, or scratch that: There are several problems. The title of the movie is Death of a Unicorn, not simply A Unicorn—the death occurs very, very early in its running time, and Rudd himself is responsible for it.

First, his character, Elliot, plows his rental car into the beast of myth while speeding along woodland backroads; then, in a misguided attempt at doing the right thing, he smashes the still-living creature to a pulp with a tire iron while his daughter, Ridley (Ortega), kneels by its fallen form. She’s right in the middle of a magical vision at the time, too, spurred when she touches its glowing horn. How many people can genuinely say they’ve seen the birth of the universe? Not many. Not even Ridley! Elliot sees to that.

By now, it is crystal clear that we can’t have nice things; the events of November 2024 to Signalgate have driven that point home with the same savagery Elliot puts behind each swing of his handy lug wrench.

Death of a Unicorn, a suitably entertaining environmental horror-comedy produced by A24 and directed by first-timer Alex Scharfman, nonetheless reminds us that not only can we not have those proverbial nice things, we should not have them, either. How would people react to the existence of unicorns when the existence of transgender people is so confounding and frightening to some?

It’s this response to the unknown, to the unfamiliar, that makes that death so upsetting to start with. “If people could put rainbows in zoos, they’d do it,” quips the tiger to the boy in a famous June ‘95 strip of Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes. Either Watterson, and the tiger, were being generous, or Scharfman, having experienced the last decade of cultural upheavals on this Earth, is being blunt; whatever the case, people would figure out how to aerosolize rainbows, as surely as the team of medical personnel working for the Leopold family, Elliot’s pharmaceutical giant employers, immediately set about exploiting the limitless curative power of the unicorn’s horn for medicinal—read: commercial—purposes.

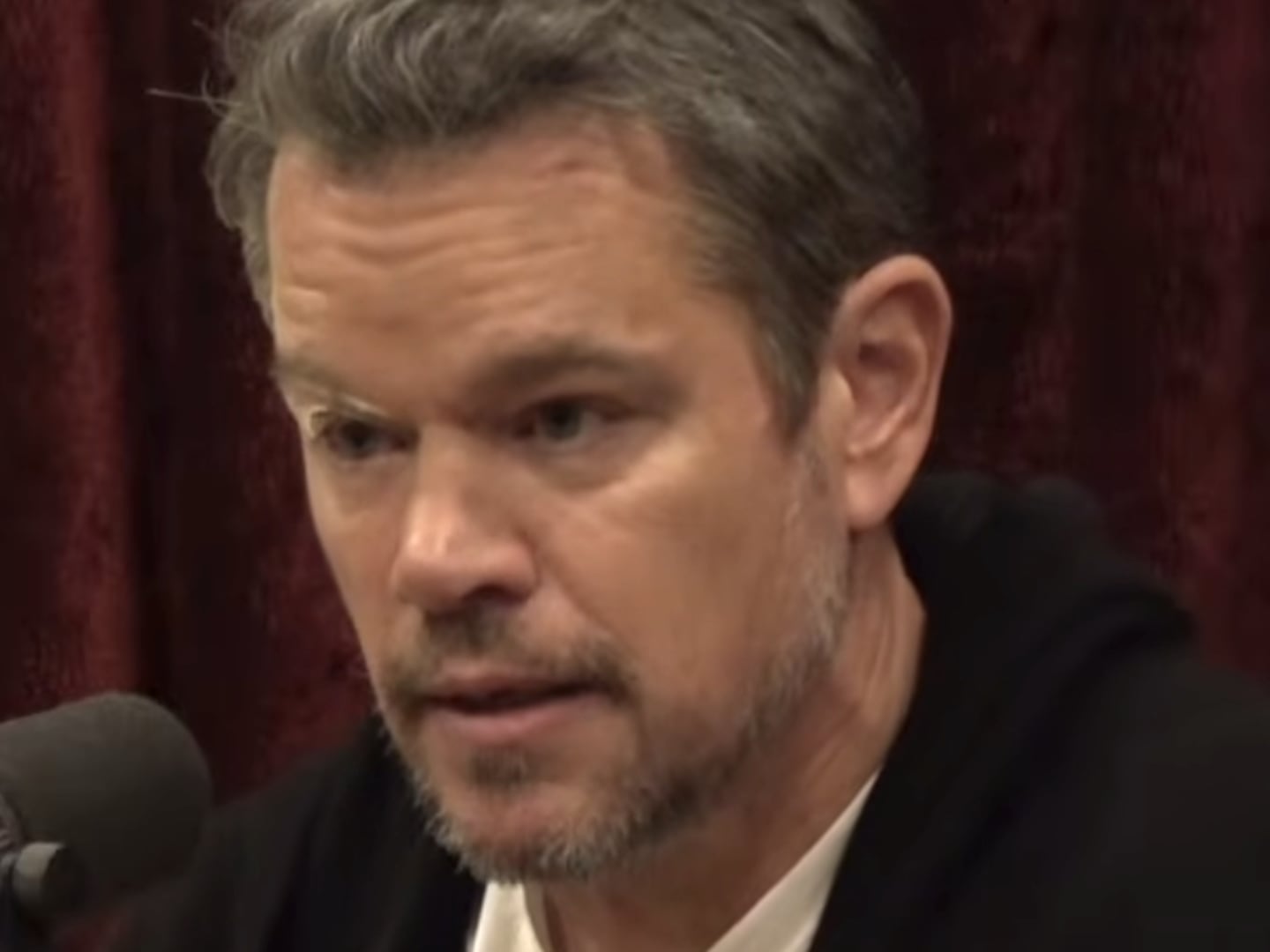

Grant that it is disturbing on its own merit when Elliot kills the beast. For one thing, spontaneous brutality is not the essence of Rudd, outside of rare exceptions like Duncan Jones’ Mute. But his overreaction reveals an animal instinct reflected later on through the actions of the foal’s furious parents, who come tearing through the idyllic mountainside, impaling or trampling or disemboweling anyone in their path to recover their child. Elliot’s actions put Ridley in danger, yes, but he believes he’s protecting her–and fulfilling his promise to her mother, his wife, who dies prior to Death of a Unicorn’s events. He is misguided, but his intentions are pure.

This is more than can be said for the Leopolds–Odell (Richard E. Grant), Belinda (Téa Leoni), and their failson, Shepard (Will Poulter)–who act in the interest of profit. Even their scientists, Dr. Song (Steve Park) and Dr. Bhatia (Sunita Mani), own more of the guilt than Elliot.

They’re just doing their jobs, of course, right up to the moment where Bhatia saws the baby unicorn’s horn off of its forehead, which feels like a greater violation than the killing itself. Unicorns, it turns out, don’t tend to stay dead. The effects of Elliot’s bludgeoning wear off after he and Ridley arrive at the Leopold’s mansion; Shaw (Jessica Hynes), their security chief, shoots it in the head at point blank range, and even that’s a temporary measure. Nicking the horn is a far more potent procedure for keeping the unicorn down.

It’s unwholesome, too. The horn is the unicorn’s symbol, the image that shimmers to mind with a casual mention of the species, and the source of its salutary magic. The opening sequence is one thing. Unusual as it is for Rudd to be the guy busting skulls in any movie other than a Marvel one (and even then, those films sanitized enough that they self-disqualify), there is a black comic effect to the way the commencing death plays out, in consolation for our provoked distress. But nicking the horn is the graver sin and the greater shock.

Viewers with sensitivities about animal violence will struggle with Death of a Unicorn; that brief is a hard sell on paper. But Scharfman manages to take the brief further, leaning into elements of fantasy and folklore to land on an act more macabre, not to mention alarming, than the killing itself. To stumble upon a unicorn in the wild would be a miracle. If the movie tells us anything, though, it’s that for as much as we might want for that to happen, we simply don’t deserve it.