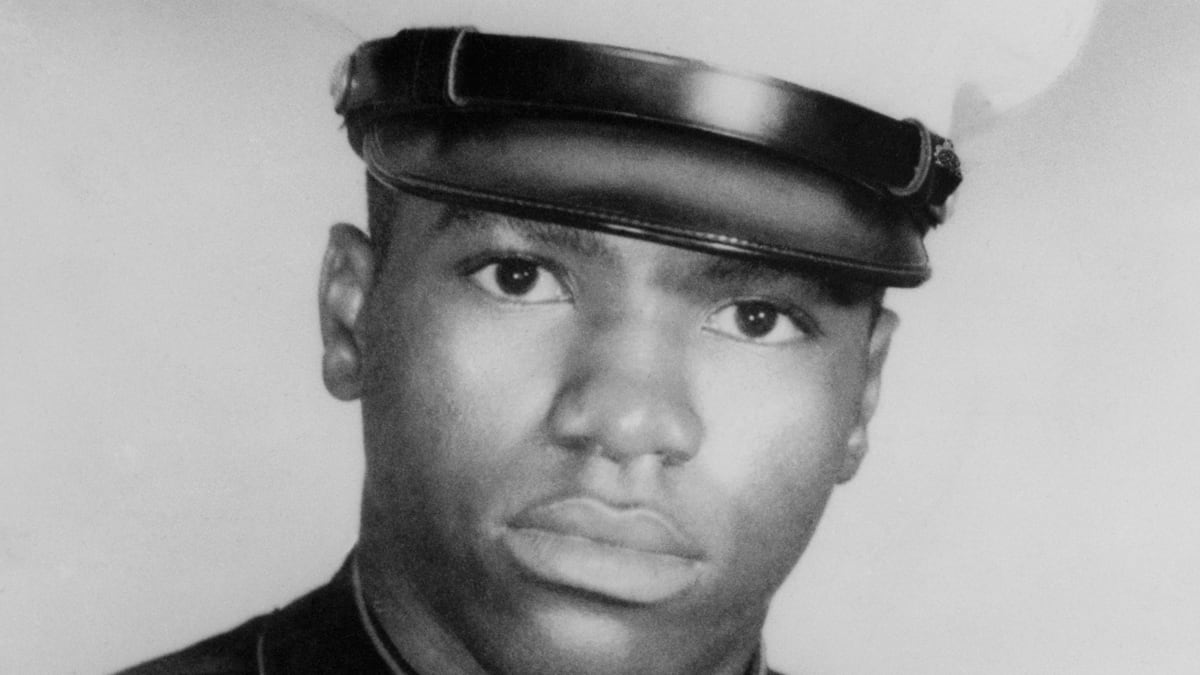

Among those we should remember on Memorial Day is Dan Bullock, who was just 14 on the September day in 1968 when he strode into a Marine Corps recruiting station with an altered birth certificate.

At a time when the nation was stunned by the Tet offensive in Vietnam and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy, this teen from Brooklyn retained a very clear goal.

“He wanted to make his mark in life,” his father, Brother Bullock, later told reporters. “He wanted to be something.”

The surrounding streets offered only trouble. The neighborhood schools seemed to promise little more. And the younger Bullock was so audaciously eager as he set off for boot camp that his family said nothing to the Marines of him really being four years shy of the minimum age of 18.

“He was all excited when he was in uniform, talking about getting up in rank,” his stepmother, Jewel Bullock, would recall to the press. “He said, ‘When I get back, I’ll have my stripes.’”

Bullock was strong and fast, but he still had no more than a 14-year-old’s stamina. He got his first sense of what resides at the core of the Corps when his fellow recruits at Parris Island had to carry him at the end of the long runs.

In April 1969, five months after his 15th birthday, Private First Class Dan Bullock arrived in Vietnam. He was assigned as a rifleman to Fox Company, Second Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment. Nobody in the unit guessed his true age, but there was a general sense that he somehow did not belong.

“Everybody who met him either wanted to protect him or push him around,” recalls Lance Cpl. Steve Piscitelli.

Piscitelli was one of those whose impulse was to protect this kid from Brooklyn who kept to himself. Piscitelli tried to draw him out.

“He wouldn’t talk,” Piscitelli says. “He wouldn’t open up. But he was 15. He wasn’t going to tell me.”

Piscitelli came to feel like a kind of older brother.

“The others just sensed he wasn’t supposed to be there,” Piscitelli recalls. “It was, ‘What are you doing here?’”

Piscitelli invited Bullock to join him in some good-natured sparring, figuring that this might establish more of a connection between them.

“He really was in great shape except for the endurance thing,” Piscitelli says.

During some playful sparring on June 6, Piscitelli dislocated his thumb. He was unable to handle a rifle properly and had to stay behind guarding the tanks when the unit deployed that night to the bunkers that ringed An Hoa combat base.

After midnight, Piscitelli heard a fierce battle erupt a mile away. He listened to shouts on the radio as the gunfire raged.

“There were a lot of Marines doing what Marines do,” Piscitelli says. “They don’t run. Marines never panic. We don’t do that. That’s why we are who we are.”

Piscitelli found out just how bad it had been when he counted the number of ambulatory survivors who came back with the dawn.

“Forty-five went out, only 20 returned,” Piscitelli recalls.

Among the five killed was Dan Bullock. His captain, Robert Kingrey, wrote to the Bullock family back on Lee Avenue in Brooklyn, describing how the night defensive position had been attacked around 1 a.m. on June 7.

“Dan immediately realized that the attack was stronger than usual and that the ammunition supply was becoming depleted,” Kingrey recounted. “He rushed to get more ammunition for his unit. He constantly exposed himself to enemy fire in order to keep the company supplied with the ammunition needed to hold off the attack. As the attack pressed on, Dan again went to get more ammunition when he was mortally wounded by a burst of enemy small arms and died instantly at approximately 1:50 a.m.”

Kingrey continued: “Dan was one of the finest Marines I have ever known. He took pride in doing every job well and constantly displayed those qualities of eagerness and self-reliance that gained him the respect he well deserved. Although I realize words can do little to console you, I hope the knowledge that we share your sorrow will, in some measure, alleviate the suffering caused by your great loss.”

The letter was preceded at the Bullock home by a Department of Defense telegram informing them that he had died from “multiple missile wounds to the body and small-arms fire.” Reporters appeared at the apartment and the grieving family told them that Dan Bullock had been only 15. Word of his true age soon after reached Fox Company in Vietnam, explaining what the other Marines had intuitively sensed.

“He felt like a kid brother who was tagging along,” Piscitelli says.

Piscitelli was wounded three times but survived and became a sculptor of note in Florida. He at first made figures of men in combat, then of ballet dancers.

“The war stuff is very hard to do,” he says.

As the Vietnam War faded in the memory of everyone save those who fought in it, Piscitelli was contacted by a former Marine named Franklin McArthur, who had been one of the recruits helping Bullock on the long runs in boot camp. Piscitelli had founded a foundation to create a memorial in Bullock’s memory, and Piscitelli joined him in raising funds for a 7-foot statue of the fallen teen who had wanted to make a mark and be somebody.

“Then 9/11 happened,” Piscitelli says. “Everybody got distracted.”

Even many Americans who had fervently opposed the war in Vietnam supported going into Afghanistan after Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda. We were on our way to accomplishing that mission when the Bush administration began diverting military resources in preparation for going after Saddam Hussein, who had nothing to do with 9/11.

Among those who joined up after 9/11 as if it were Pearl Harbor, only to be sent to Iraq rather than after bin Laden, was the son of a New York City firefighter who died in the South Tower of the World Trade Center. The son, who asks not to be identified for security reasons, became a member of the U.S. Army’s Special Forces. When he looked inside his first green beret, he saw three words that testified to how quickly a war can be forgotten:

“MADE IN VIETNAM.”

The words also served as an increasingly wrenching reminder of a particular war whose lessons we failed to heed first in Iraq and then in Afghanistan. We did finally manage get bin Laden, nearly a decade after we might have had we not been diverted, but now some of our finest young Americans are dying in a futile war from which we are seeking only to extricate ourselves.

At least some citizens in Brooklyn remembered the Marine who died at just 15 in Vietnam. The block where he once lived was officially renamed PFC Dan Bullock Way in 2003.

And a photoengraving of an impossibly young Bullock in dress uniform is part of the seldom-visited Vietnam Veterans Memorial tucked away at the edge of Manhattan’s financial district, where greedsters nearly wrecked the nation’s economy in the midst of our two most recent wars.

Across the top of the memorial to those who died demonstrating the supreme opposite of greed, is a poem by Army Maj. Michael O’Donnell. He wrote it shortly before he was killed while piloting a helicopter in an attempt to rescue a Special Forces team. It is a poem well worth reciting on our national day of remembrance.

“If you are able,save them a placeinside of you.And save one backward glancewhen you are leavingfor the places they canno longer go.Be not ashamed to sayyou loved them,though you mayor may not have always.Take what they have leftand what they have taught youwith their dyingand keep it with your own.And in that timewhen men decide and feel safeto call the war insane,take one moment to embracethose gentle heroesyou left behind.”

The bigger-than-life statue of Dan Bullock has not gotten beyond a 2-foot wax prototype, though Piscitelli continues to sculpt ballet dancers. He tries to complete one a month.

“It keeps me from thinking about the war,” he says.

While millions of us head for the beach or hold cookouts on Memorial Day, Piscitelli goes into seclusion, ignoring the phone and thinking of Bullock and all the others.

“That’s my high holy day,” he says.