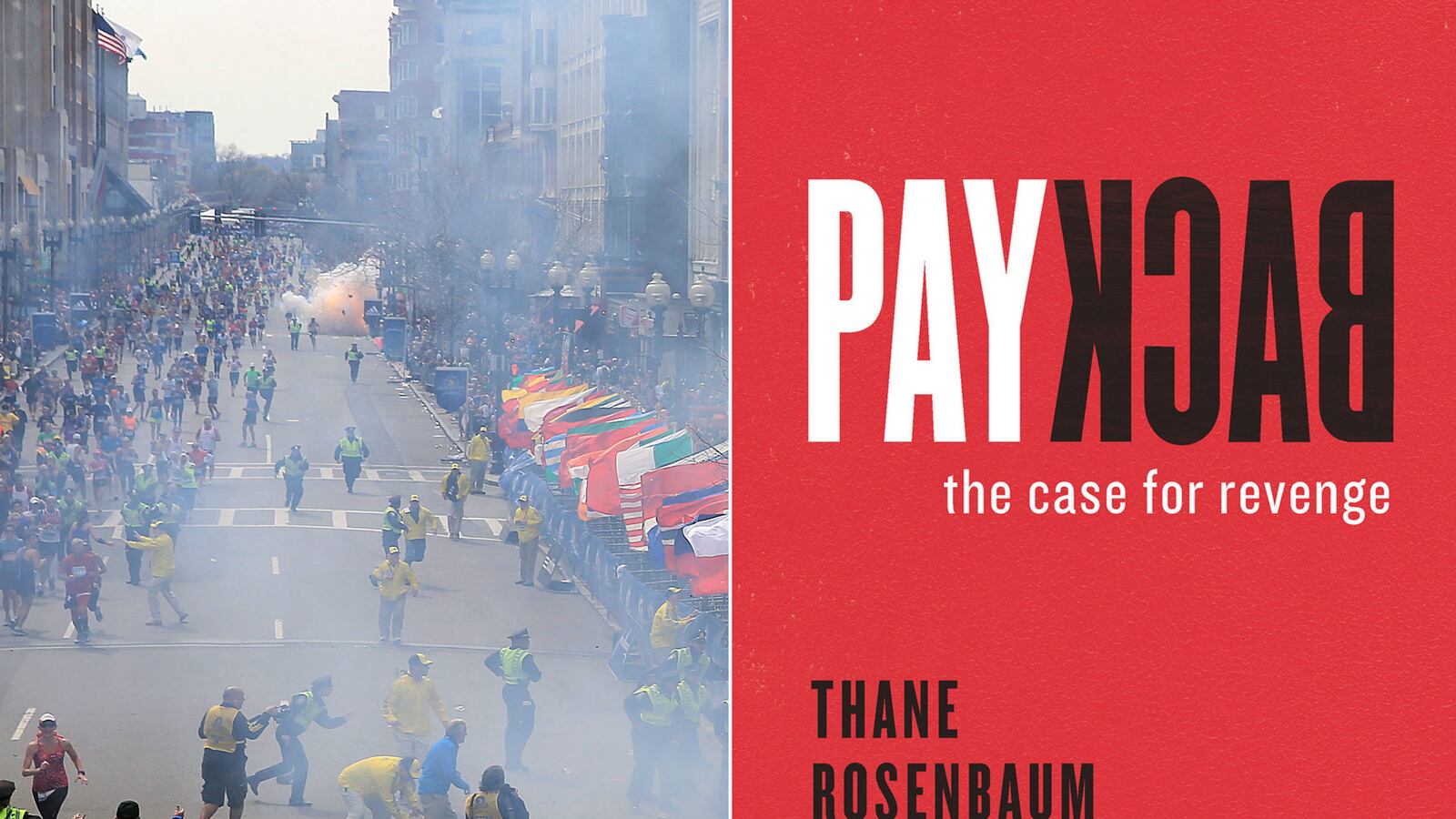

Order has been restored to Boston after the terrorist bombings near the finish line of its Marathon, but the feelings of anger and rage directed at the two alleged terrorists—and whatever accomplices can be tied to this crime—is very much unfinished business.

One of the two attackers, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, was fatally wounded in a shootout with police, while his younger brother, Dzhokhar, remains under medical care and awaits his date with American justice. He has already been questioned, if not perhaps interrogated, by the FBI. Only then did he receive his Miranda warnings. Three of his friends, who were either complicit or simply misguided, have been arrested, as well. And, of course, Tamerlan’s widow may end up in custody now that it has been discovered that the bombs were actually built in the tiny apartment she shared with her husband and young daughter.

Get ready: The prosecution of this horrific crime that took place on Patriots Day will no doubt be influenced by the special provisions, and civil rights exceptions, of the Patriot Act.

Many who are not card-carrying members of the ACLU, however, and especially those who live in Boston, will not be distressed by this infringement of constitutional protections. And few Americans will weep should Tsarnaev be sentenced to death.

Why? Because most will feel that such an outcome will be the justice he deserved given the magnitude of the crime he committed. Far fewer will admit, however, that this demonstration of justice might also serve as an act of vengeance.

Of all life’s many vices and human failings—betrayal and envy, promiscuity and addiction—revenge may be the one laboring under the most extreme prejudice. After centuries of societal scorn, religious edicts and governmental warnings, it’s nearly impossible to have an honest conversation about revenge.

No one wants to be regarded as vengeful. People will admit to almost anything other than possessing a vengeful streak. Even sexual perverts have it better in polite company. But as vices go, vengeance was always a virtue in disguise, a perfectly healthy response to moral injury.

The vengeful are perceived as out of control, one click away from unhinged. All those messy emotions, the obsessive thoughts, the clenched teeth, are considered boorish and barbaric. Civilized people keep their anger in check, and never act out their rage. It’s best for the nascent avenger to either turn the other cheek or simply let justice run its course.

But is that a virtue? Among the ancient Greeks, Aristotle was certainly not one to regard the suppression of justifiable anger as admirable. Failing to vindicate a loss or injury is a sign of faulty moral character. What kind of a person doesn’t stand up for himself?

No one wishes to live in a world where all are excused from their evil without penalty. Just think of Adolph Hitler, Pol Pot, and Osama bin Laden. Granting forgiveness to those who qualify as the “worst of the worst” is cheek-turning on steroids, and therefore morally unbearable.

Yet, vengeance can be confusing. Despite all the prohibitions against it, everyone practices revenge on some level, applauds it when properly exercised, and even dreams about it in their sleep. We see it daily in schoolyards, sports arenas, and halls of Congress; we know that it lurks within the messy details of international affairs, domestic relations, business dealings, and, of course, legal battles.

Indeed, some of the most riveting feature films have been tales of revenge—Braveheart, Gladiator, Death Wish, True Grit, and The Searchers. There is great moral clarity in payback. Vengeance is what is owed—without qualification, without apology. The avenger is never mistaken for an outlaw. Indeed, it is the law’s failure that gives birth to the avenger, who very often is reluctantly called into the service of righting a wrong.

Yet in the real world where tidy, morally satisfying endings are not projected onto a silver screen, self-help is deemed a crime and avengers are treated as common criminals.

Actually, legal systems are the worst culprits in this backlash against revenge. It is the illusion of the law serving as retaliatory proxy that convinced citizens to surrender their right to revenge in favor of the rule of law. But this also came with reciprocal obligations, for which legal systems are often in breach: The law, all too often, never comes close to achieving an “eye for an eye” justice; victims are nearly always deprived of the satisfaction of knowing that they have been avenged. The voices of victims are rarely heard, the acknowledgement of what happened to them, personally, at the scene of the crime, is virtually an afterthought. The debt that wrongdoers owe them is trivialized, the byproduct of plea bargains where over 96 percent of all criminal cases are settled with reduced punishments.

America’s war on terror has presented its own set of confusions. Shortly after 9/11, in setting the stage for the retaliation that was about to be visited upon Afghanistan and then Iraq, President George W. Bush told the world that, “Ours is a nation that does not seek revenge, but we do seek justice.” The vast majority of Americans applauded (as they have many times since).

But what did he mean by “justice”? Surely he never intended to commandeer the courthouses of Kabul where we would square off against the Taliban—lawyer to lawyer. Our manner of achieving justice certainly looked a lot like revenge. The president had recast our vengeance by invoking the words of justice, thereby seizing the legal authority to bomb the hell out of another country—all without seeming vengeful.

Years later Osama bin Laden was assassinated even though it’s possible he could have been kidnapped and brought to America for an appointment with justice. And it was a Democratic president who ordered that mission, and a former constitutional law professor at that. Shouldn’t “justice” have coincided with a legal trial? Yet, most people cheered the justice bin Laden received, and didn’t feel as if they were complicit in compromising our values in doing so. Similarly, just hours after the newest installment of the Boston Massacre, President Obama vowed that whoever is responsible “will feel the full weight of justice.”

What will “the full weight justice” look like, and will it matter to most Americans so long as it satisfies our emotional need and moral right to be avenged?