I became a prosecutor because of Trayvon Martin. I used to be him, black, baby-faced, and 17. The times I wasn’t being harassed by police and security guards, I was being harassed by young African-American men. Stopped and patted down by the former, robbed of my lunch money by the latter.

The difference between Trayvon and me is that I survived. And then I wanted to use my Harvard Law school education to address the two most vexing criminal justice issues for blacks—over-enforcement of the law and under-enforcement of the law—at the same time. So, in the early ’90s, I joined the United States Department of Justice as a trial attorney.

My plan was to go in as an undercover brother. It’s the classic liberal response—to infiltrate the oppressor to try to create change from the inside. I thought nobody would be in a better position to make a difference than me.

Young black men are frequent victims of crime, and the most likely to be charged with crimes. I could have responded the way that lots of my brothers do—by not trusting anybody. You walk through your ’hood, and you glare at the dope boys on the corner who make your community feel unsafe. Then, when the squad car slowly rolls by, and the cops take a good look at you, you glare at them too.

But I was an idealist. And being a prosecutor seemed to be the perfect solution to long-standing concerns that African-Americans had about both civil rights and public safety. In the segregated neighborhood in Chicago where I grew up, blacks made the same claims about law enforcement that they do now. The times that my neighbors were not complaining about how the police treated them, they were complaining that the police were never there when they needed them.

These claims seemed contradictory, but they were both accurate. And unfortunately things have not changed much, 30 years later, when the United States has one black president and 1 million black people in prison.

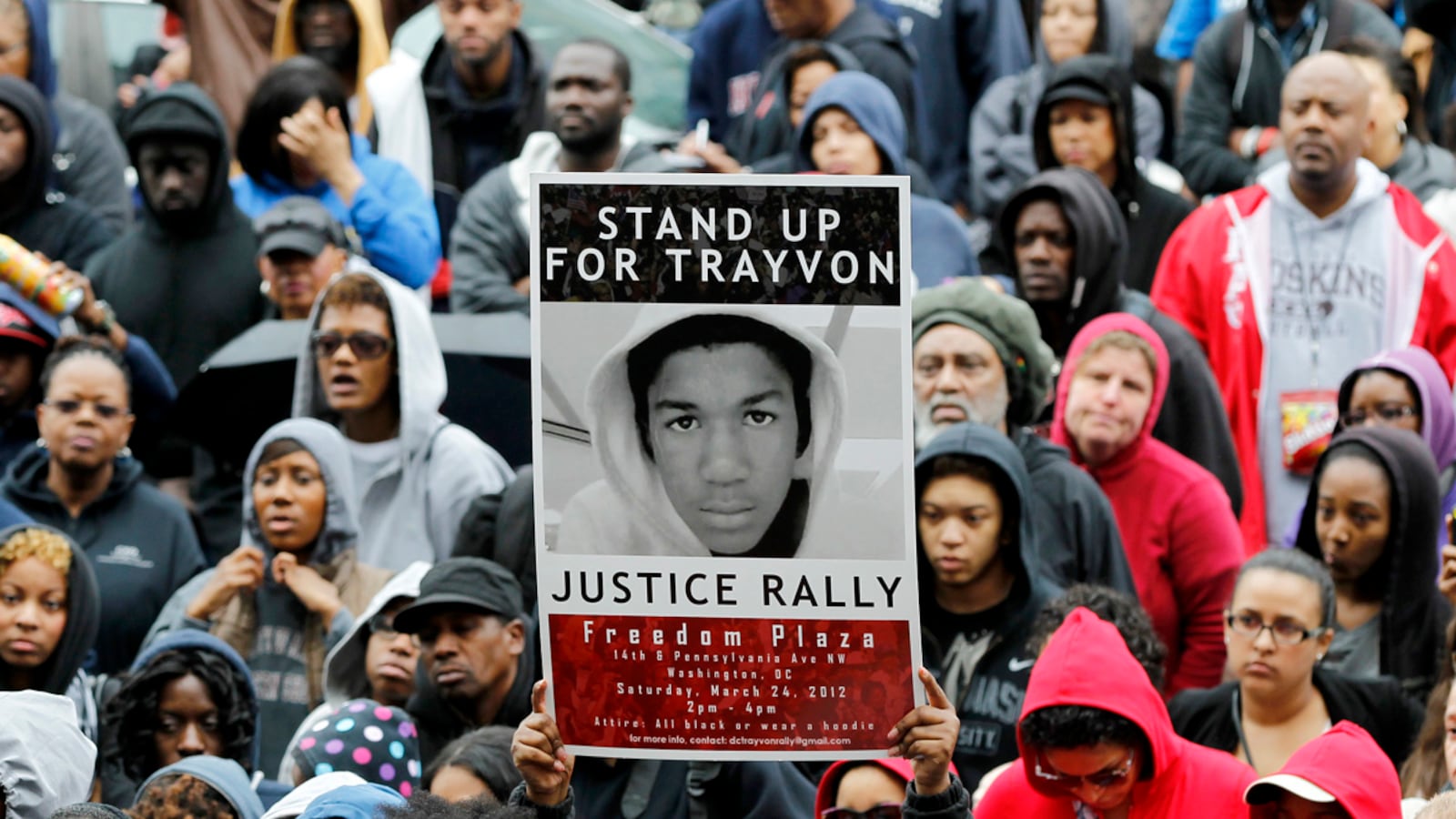

The citizens of Sanford, Fla., need the police right now. And they are not there. There are more African-Americans in the criminal justice system than there were slaves in 1850. Yet no law enforcement official has found the time to arrest George Zimmerman, more than a month after he followed Trayvon Martin, got out of his car to confront him, and then shot him dead.

The black prosecutor lives at the intersection of crime control and racial profiling. I think that many fail to make the difference that they hope to because their tool—locking people up—is too blunt an instrument. In the adversarial system of American criminal justice, prosecutors are forced to choose a side. So they end up defending the police and locking up a lot of black people.

Who gets prosecuted in the United States is politicized, and it’s racialized—the situation in Sanford is just the most dramatic recent example. The cities that have the highest number of incarcerated blacks are often the same as the ones with the most black prosecutors.

But when black prosecutors talk among themselves and say “I wouldn’t trust this guy in a dark alley,” they could be talking about the police as easily as their most recent defendant. Black prosecutors are still black, which means they have stories about being racially profiled.

People ask if, when I got stopped by the cops as a prosecutor, I told them what I did for a living. Yes, but it didn’t always make a difference. It didn’t make a difference the time I told the cop that I was a prosecutor, and he smirked and said, “So you probably know this already”—and then he read me my Miranda rights.

I became a prosecutor because I wanted to help victims, and not be one—of the police, or of another black man. The fact that Trayvon Martin was killed by a non-black man is one of the reasons that this case is so high profile. The police have a name for the more typical black-on-black crime: routine homicide. The closure rate on those cases is often less than 50 percent. And nobody marches or signs petitions or puts those victims’ photos on their Facebook wall.

So there is still a crying need for law-enforcement interventions that work to keep communities of color both safe and free. And for law enforcement to understand that racial profiling is counterproductive to this effort. Too often police and prosecutors just don’t get it.

For example, officers of the New York Police Department, in certain black and Latino neighborhoods, act like slightly less trigger-happy George Zimmermans. They stop black and Hispanic men for virtually any reason, and they rarely find anything incriminating. In one neighborhood, the cops made more than 40,000 stops, and found just 25 guns—a hit rate of less than 1 percent.

Meanwhile, violent crime in that community is going up. The tragedy of racial profiling is not only that it’s ineffective; it makes many of its victims hate the profilers—whether they are police, security guards, or neighborhood-watch people. And that causes a breakdown in trust that makes public safety even more problematic.

The “smart on crime” movement led by some progressive prosecutors, like Craig Watkins, Dallas’s district attorney, and Kamala Harris, the attorney general of California, is a limited reason for optimism. This movement focuses on reserving incarceration for violent crime, and repairing relationships between the police and disaffected communities. The U.S. Department of Justice, under Attorney General Eric Holder, also has promoted reconciliation between law enforcement and African-Americans.

Efforts like these are the best way to honor the memory of Trayvon. Like all citizens, blacks deserve both their civil rights and the equal protection of the law.