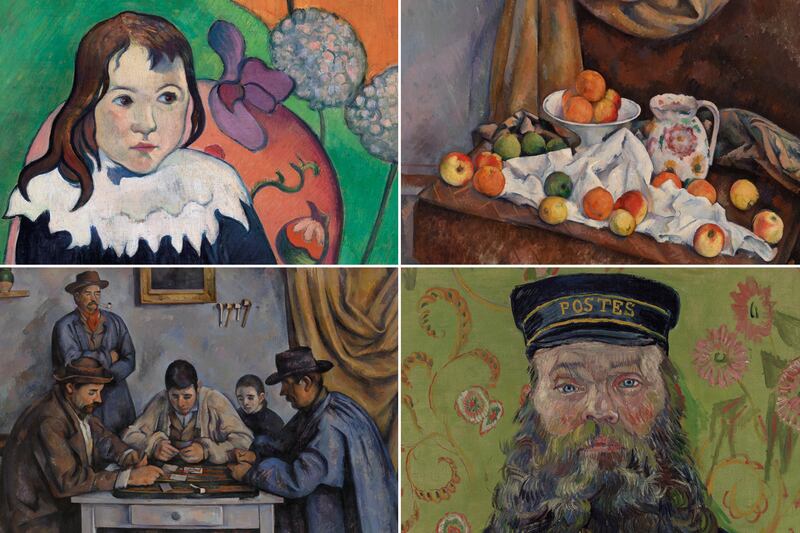

Albert C. Barnes, Philadelphia’s Argyrol King, was a crabby tycoon whose peculiar, sometimes noxious ideas about art have been pretty much irrelevant since the day he died, in 1951. And that may be why his amazing collection—4,323 objects, including 69 Cezannes (mostly masterpieces), 181 Renoirs (mostly cotton-candy nudes), piles of Picassos and Matisses as well as Goyas and El Grecos—gives such absolute pleasure today. His ideas now have so little leverage, viewers of his pictures feel free to think (and enjoy) as they please.

Barnes’s art spent decades tucked away in Merion, a suburb on Philadelphia’s tony Main Line, but on May 19 it goes on view in a posh new building in the city’s cultural heart. The Rodin Museum and Franklin Institute are now the collection’s near neighbors, and the great Philadelphia Museum of Art is just up the street. At the press preview for the “new” Barnes Foundation, I spent more than seven hours going from room to room, picture to picture, drinking in the glories on offer. That was double the time I can normally spend before getting hit by museum fatigue. There’s something about the scale of the Barnes galleries, and the way the pictures are chosen and hung, and then the light and air that the new building grants them, that keeps an art lover from flagging. (It doesn’t hurt that there’s a bench in every room—a museumgoer’s right that should be enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.)

Old Albert Barnes can take credit for some of this success. Born in a Philadelphia slum in 1872 and then trained as a doctor at Penn, he made a fortune from Argyrol, a trademarked eyedrop that helped treat gonorrhea in infants. (Before antibiotics, most newborn eyes were treated with an antiseptic, and Barnes pushed Argyrol as the cure of choice.) He became a serious art collector around 1912 and, partly to spite his enemies among Philadelphia’s snobs, he bought deep from Europe’s radical edge.

His Cezannes show the Frenchman at his most kaleidoscopic, breaking the world into shards. Barnes bought great Matisses and Picassos, Seurats and Modiglianis—even a pornographic Courbet—when such art still counted as out of bounds, at least in Philadelphia. (Weirdly, he mostly avoided Cubism, even though he got wild Cezannes that foreshadow that movement.) Barnes amassed Old Masters that he felt had a modernist essence—those El Grecos and Goyas, but also medieval and Renaissance works—as well as African sculpture and American folk art and ironwork and hope chests.

His collection was all wrapped up in the idea, standard for his time, that all that really mattered in art was what it looked like to modern eyes, without regard for meaning or an artist’s intent. A Christian altarpiece, a Picasso experiment, an African ritual mask and a bunch of old hinges could all keep fine company on a millionaire’s walls.

In 1925, Barnes dedicated a grand gallery to house his art and foundation, as well as a school that spread his ideas to select acolytes. Over the years after his death (he ran his Packard through a stop sign and into a truck) a larger public gradually edged its way in, but never in very big numbers. Things eventually soured for Barnes’s foundation, and in 2002, a consortium of cultural players strong-armed their way into power. After edging out the black college that Barnes had left in control (again, he was partly out to spite Philly’s mighty), those players convinced a judge to permit the unthinkable: to allow an “educational” collection that was supposed never to be moved or changed, or to open to an ogling public, to head downtown and throw its doors wide as a museum and tourist draw. (The story is amusingly set out in The Art of the Steal, a ferocious “anti-move” polemic by the documentarian Don Argott. His worries about the new Barnes becoming part of the entertainment-industrial complex are hard to dismiss.)

So the collection fell into the hands of the Philadelphia establishment Barnes hated … and mostly that’s been a good thing. More people can see the art, in better conditions than ever before. Numbers will be limited to avoid overcrowding, but that still leaves one major caveat: although the move from the suburbs has put the collection much nearer to the disempowered masses and minorities that Barnes had cared about, an $18 ticket charge will help keep them away. Some part of the hundreds of millions raised for the move should have been set aside to keep admission free.

The new Barnes building is no masterpiece—it is done in a very pleasant, slightly decorative version of 1960s modernism, like Lincoln Center in a more restrained mode. But that’s fine, since it really just functions as a box (it almost feels like a mausoleum or memorial) in which the old Merion rooms have been rebuilt and rehung and, especially, relit with natural light. Nearly every painting and African mask and fire-iron has been positioned as it was when Barnes died, to within 1/16th of an inch. At first, this fetishism comes off as an absurd homage to curatorial ideas that were hardly worth saving. Once we’ve so clearly blown off Barnes’s stated aims for his foundation—and why should we be bound by the desires of a long-dead millionaire crank, anyway?—there may not be much point in preserving his notions on how art should be hung.

As Barnes director Derek Gillman told me, “We’re carrying forward a ‘teens and ‘20s Anglo-American modernism”—and even Gillman isn’t perfectly sure why, except out of duty to Barnes himself. Not a single curator in the world would think to serve up great Cezannes and Matisses—or ironwear and African masks—as the Barnes is now doing. But here’s the strange thing my joyous visit suggested: maybe they should.

The collection’s folk art and ironmongery doesn’t really come off as equal in importance to the masterpiece paintings nearby, as Barnes had intended. Instead, Barnes’s hinges and buckets act as a kind of soothing white noise, a place to rest your eyes between glances at his ferocious Cezannes. Instead of paying attention to the specious unity that Barnes asserted between Old Masters and Africans and moderns, you can treat the contrast between them as a chance to shift mental gears. But more than anything, Barnes’s hang now comes off as so nearly arbitrary that it frees you to come up with your own ideas about what the art means, and what’s worth looking at next. (There are no wall texts or even labels to distract or instruct you. Brochures tell you what’s hung in each room.)

I’ve often thought I’d like to see a museum arranged alphabetically by artist, so I wouldn’t have to follow any aesthetic agenda but mine. The ideas behind how Barnes’s pictures are hung are now so outdated, so irrelevant to our current concerns about art, that the objects might almost have been put up at random. And that, for once, puts all the power in the hands of the viewer. Actually, I’m not sure that Barnes, the contrarian populist, would have detested that outcome.