We all have our intriguing visions of perfect lives, from the glamorous people who star in them, to the happiness that permeates them, and the ease with which they appear to be lived. But beneath the polished surface of perfection, there’s always a surprising roughness. Polly Samson’s collection of 11 interlinked stories, Perfect Lives, reveal the cracks in the façade of perfect lives, the “something small but monstrous” that creeps into happy marriages, divides families, and storms in on picturesque scenes of a wealthy, seaside town.

Samson’s nuanced tales delve into her characters’ relationships and lives, and though one character may be unaware of another’s existence, the reader is privy to their entwined secrets and pasts. The collection’s opening story introduces Celia Idlewild, a wife and mother of two who clings to the idea of a once-perfect marriage, even after learning that her husband is cheating on her. Samson’s stories are dark and melancholy by nature, but she infuses them with stylistic grace and humor and in turn delivers an uplifting message. In “A Regular Cherub,” a woman named Tilda condemns herself for thinking her newborn looks “like a Christmas gammon, boiled and ready for stuffing with cloves”; the simile is odd and even disturbing, but Tilda’s strange, self-mocking comparisons help her find light in the gloom of post-partum depression.

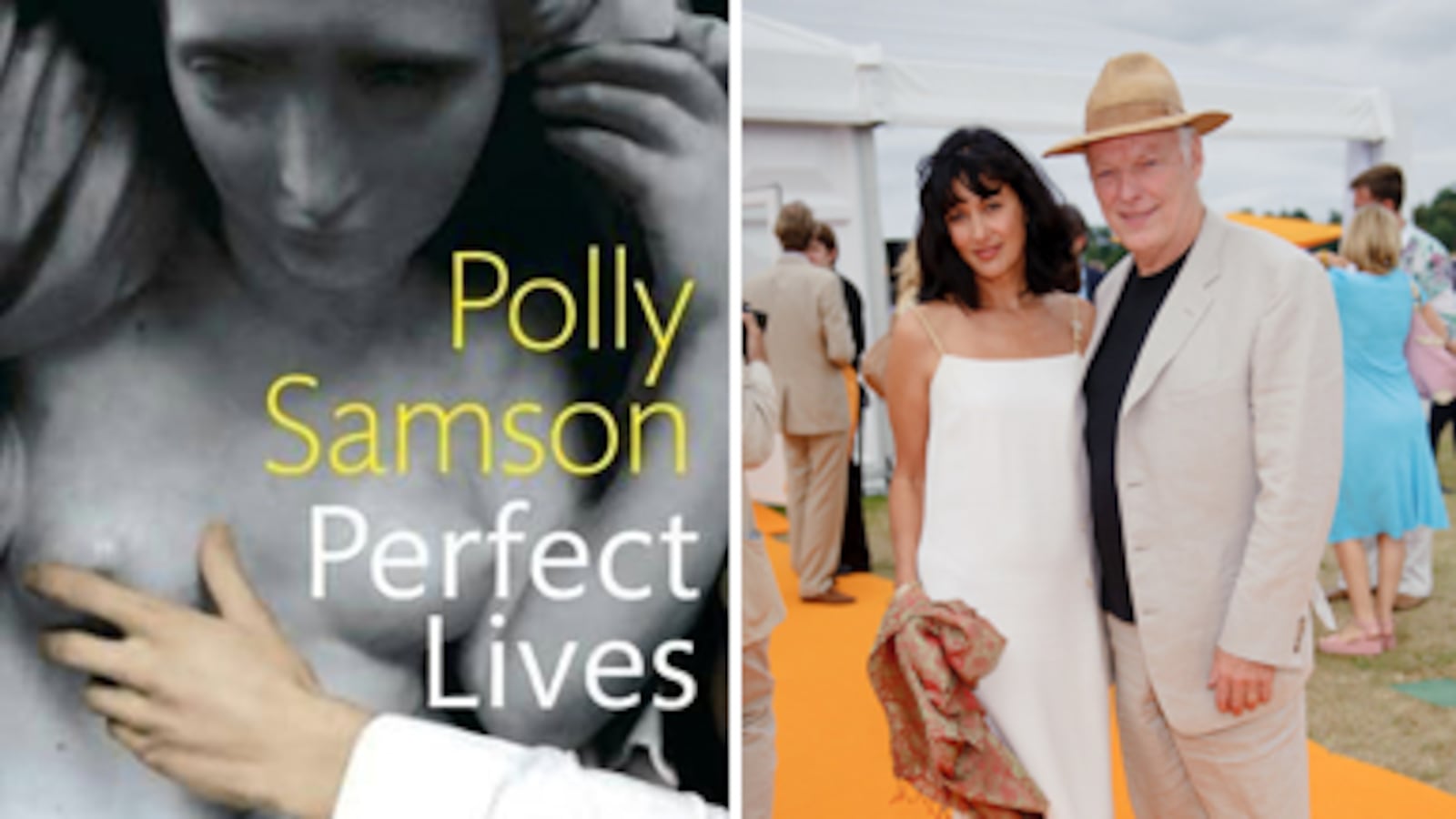

The stories in Perfect Lives are strung together by Samson’s poetic narration, her sumptuous descriptions of longing and desire, whether in conjuring a lover’s savory scent (“buttered toast, walnuts, and bread”) or a piano’s beauty (“20 tons of exquisite tension… held like a drawn bow inside gleaming rosewood”). However accurate, it may be redundant to say that Samson’s prose is lyrical, given that her husband is David Gilmour and she has written lyrics for Pink Floyd’s last album and Gilmour’s third solo album.

The Daily Beast spoke with Samson last month.

You made your debut as an author in 1999 with your collection of stories, Lying in Bed, and the following year you published your first novel, Out of the Picture. With February’s release of Perfect Lives, how have you developed as a writer over the past 10 years?

One of the biggest surprises when Lying in Bed was published was how often I found my stories referred to as “dark.” When I worked as a journalist, I paddled around in the shallows of the Sunday Times, usually writing features that needed jokes. I’ve always enjoyed hearing that something I’ve written has made someone laugh, so all this “darkness” was a revelation. “Wry” kept cropping up in the reviews too, but that was less unexpected. I hadn’t yet had this confirmation of “a darker place” when I wrote Out of the Picture. I finished the novel in a frenzy before Lying in Bed was published with paranoid thoughts that the reception of the stories might make the ink freeze in my pen forever more. Perfect Lives comes from a warmer, more confident place. I didn’t need to rush it and when it was finished I liked it more than anything I’d written before—its light and its shade—and for the first time in my life I had no qualms (and this is really out of character) about letting it go out there to find readers. So, I suppose that if I have developed at all it is that I am writing from a more confident place.

The title of your story collection is of course replete with irony. Your stories teach us that there is no such thing as a perfect life. Would you say that the imperfect, tragic moments in your stories make your characters’ lives all the more interesting and full?

I listen to Leonard Cohen’s song “Anthem” where the chorus goes, “There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in,” and think how brilliantly he expresses in that song what I think Perfect Lives is about. Seekers of perfection lead unhappy lives. Perfection is fleeting. One of the characters in Perfect Lives is Richard, who finds perfectionism costs him his career as a concert pianist; another is Celia, whose carapace of a perfect marriage is as brittle as eggshell. Things get broken and for all my characters it is only when they accept imperfection that things get better. Some things can’t be repaired but it takes a broken heart to understand the true meaning of love, or a moment of discord to make the tune.

From an outsider’s perspective, your life might seem as close to perfect as anyone’s could be, as a rock star’s wife with four beautiful children and a fulfilling career of your own. Yet in reading your stories and witnessing the depth of your emotional vocabulary, we can guess that you too have endured disappointments, had your heart broken. Is there one story that strikes a particularly personal note with you?

I don’t think anyone has a perfect life; the most we can strive for are a few perfect moments. Even in the midst of heartbreak, I try to capture a perfect moment: scenes in this book like Celia’s erotic encounter with a statue in the Idlewilds’ sunlit garden or the moment that Richard is alone with a 1922 Bösendorfer piano are a pleasure to write. The most personal story in Perfect Lives is “Leaving Hamburg.” It’s a love letter really to my Jewish grandmother who was from Hamburg. She had to put her children onto the kindertransport to save them and didn’t get out of Germany herself until the following May: 1939. I regret now how little time I had, as a callow teenager, to really listen to what she had to say. She had been dead for 20 years when I was in Hamburg in 2005 for a concert that my husband was playing. Taking photographs from the stage as the audience called for an encore, I was (like Aurelia in the story) suddenly struck by a huge and unjustified rage: I was furious with all the faces that I saw through my camera. I craved an apology for something that had been done not to me, and that they hadn’t done. The following day, David and I drove to what had been my grandparents’ house. The phrase “secondhand memories blew about the Hamburg streets like litter” came into my head and the story wrote itself after that.

In Perfect Lives, determined and sometimes desperate attempts to attain perfection tend to backfire. As a gifted writer and lyricist, do you ever find yourself—like some of your characters—aiming for perfection, only to end up veering towards self-destruction?

During the 10 years between books, I started to take piano lessons, proper formal ones, with my children’s teacher. Initially I did this because I thought it would encourage them. Ha! What I hadn’t known was what an obsession it was to become. I longed to play Chopin; couldn’t wait to make his Nocturnes my own. I practiced hours every day, even—I’m sorry to say—batting the children away when it was their turn to play. The children’s teacher said she’d never had such a dedicated student before—Scales? Arpeggios? Little thrilled me more—and before I knew it she had me taking piano exams. There was no time to write. In order to excel at each of these exacting and excruciating tests, I was expected to play three pieces to perfection and that took all the hours I had. It’s because of self-destructive perfectionism that I went through with exams where my hands shook so badly I could barely touch the keyboard. I was so pleased when writing took over and the character of Richard was in place so I could [project] all of that on to him. It didn’t feel so self-destructive once it bore fruit.

Many of the motifs and themes from Perfect Lives—the ocean, pianos, memories, insatiable desire, longing for an unattainable perfection—seem to resonate in the lyrics you wrote for Pink Floyd’s last album, The Division Bell, particularly in the songs “Take It Back” and “High Hopes.”

I think what links “High Hopes” most strongly to Perfect Lives is the feeling of nostalgia in the lyrics, especially nostalgia for things that are not yet the past. I like the line from the song: “Steps taken forward then sleepwalking back again,” and in my stories I aim to show a person’s past living alongside their present.

I was thinking too about the lyrics of On an Island and how close the themes of the album are to the themes in Perfect Lives. I suppose my preoccupations will remain the same whatever form the writing takes. Lyrics and fiction feel closely related, probably especially because I write lyrics that someone else will sing. In that way it’s a similar act of ventriloquism as giving words to a character.

Your husband discussed The Division Bell in an interview in 1994, and said that "High Hopes,” the album’s seminal composition, originated from a phrase that you suggested about how “time wears us down.” Time certainly wears down the characters in Perfect Lives, yet they somehow survive and even find joy amid the inevitable losses that come with the passage of time.

Someone played us a version of “High Hopes” sung by Gregorian monks last night and it was strange to hear this hallowed choir making the simple ending, “The endless river, forever,” sound more mournful than when David performs it. Although there are dire situations in Perfect Lives—a mother who has news of a genetic illness to pass on to her daughter; a woman who does not love her baby; a man with a secret child—I was pleased that people found the book optimistic. I liked that Esther Freud called it “life enhancing”! Tilda lives a dreary existence in the book, she’s been dragged away from her aesthetic life to live on a muddy farm. Tilda learns that happiness lies in staying focused on something, that it sneaks in the back door while you’re at something else, that there is always the gleam within the gloom. That’s what I think too.

Lizzie Crocker is an editorial assistant at The Daily Beast. She has written for NYLON, NYLON Guys, and thehandbook.co.uk, a London-based website.