Somewhere in Jordan, a woman is being served breakfast in a painting that features a “prophet” who is trying to lure people away from committing honor killings.

“It is a bit controversial,” said Ali Maher, an artist based in Amman. “I want to shake society. I want to change the rules.”

***

Somewhere in Pakistan, the images of peacocks, curvy drapes, and droopy flowers engraved on steel, mask the suicide vests and missiles on the wall hangings that represent Karachi, a city plagued by terror and crime.

“Life and death is so uncertain now… I wanted to camouflage the horror by making it beautiful,” said Adeela Suleman, a Pakistani artist.

***

As a high tide of violent episodes sweeps across the Muslim world, artists in these countries are responding to their evolving psychological landscape with daring narratives of the drama around them.

Maher and fellow Jordanian artist Abeer Seikaly tackle the problem of honor killings in a painting that has a The Last Supper-esqe vibe.

In this piece, a woman is served along with mansaf, the national dish of rice and meat served with special yogurt. The meal is shared by a motley crew of guests depicted as ghoulish men and nude women.

“ Mansaf is meant to unify everyone [at] the table… You eat it with your hands, and here there is also a human sacrifice with it,” said Seikaly.

An empty chair on the side invites the viewer to join the feast. The chair holds a special meaning for Maher, who faults society, more than the killers, for tolerating honor killings.

GALLERY: Honor Killings and Suicide Bombs in Art

“While these acts are horrifying, all of us just doing nothing is more perverted,” explains Maher. The painting is also influenced by the Jordanian custom of atwa—a way of making peace between warring clans.

The artists explain that in the case of honor killings, atwa involves the family of the aggrieved party meeting the family of the guilty party (in case the perpetrators of the crime are not the girls’ own immediate family), and calling it a truce.

“What can be more tragic,” said Seikaly.

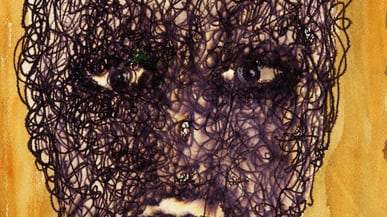

An accompanying set of smaller paintings peeks into the individual stories of the diners at the table. One image presents a closeup of a weeping woman who could be the victim on the table, and another zooms into a green bottle, held by one feaster, which now spills a red liquid.

The plotline is up for interpretation and the artists don’t mind that it never adds up. “It is an artistic interpretation of a shit tradition,” said Maher.

The duo’s untitled painting, however, will not be available to the public. Due to its nude content, the painting will only be displayed in an underground exhibition that Maher is organizing. “It can’t be shown in our part of the world,” said Seikaly.

The painting is currently hanging in Seikaly’s parents’ home in Amman.

Meanwhile, Suleman’s reaction to the violence that plagues Pakistan hangs in New York City.

Her work describes how people in Karachi have internalized the elements of risk and fear as they cope with suicide attacks and targeted killings in the city. In part, her ideas are shaped by the 24/7 trepidation she experiences for her children.

“I am a mother, and this is how paranoid I have become,” she said, at the Aicon Gallery in New York City, where her exhibition, After All, It’s Always Somebody Else, is on display through Saturday.

Suspended from the ceiling are a pair of steel curtains made up of dead sparrows joined at their beaks and tails, which symbolize the victims of terror attacks.

Suleman will tell you that she tried to count the number of people who died between the time she started working on the project and it when went on display. “I was trying to keep pace but couldn’t,” she said.

Together, the different pieces weave an intricate tale that is both intense and scenic. In one piece, two peacocks perch on what appear to be regal columns but are in fact missiles that flank four snakes embracing a blooming lotus.

It’s “the paradise that is promised after death,” explained Suleman. “And the lotus is for purity, as are the young boys before they are indoctrinated.”

Putting objects of terror in these pastoral settings is an attempt to view death without being morbid. But there is no escaping the morbidity, especially as the artist talks about the general numbness that surrounds death when news channels dole out the number of casualties. “We celebrate death now on television,” said Suleman.

A tinge of old wives’ tales is injected into the overarching theme of human apathy. The parrots in the images, for instance, are there to witness the events and tell the stories to other nations when they fly off.

But most of all, the duel of life and death in the images is a tribute to the resilience of the city and its people. “Karachi is unbelievable… no matter what happens, it keeps moving,” Suleman said.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Betwa Sharma is the New York/United Nations correspondent for the Press Trust of India and an AOL News Contributor. Her freelance work has appeared in several outlets including The Huffington Post, The Global Post, Time.com, Indian Express, Hindustan Times and Columbia Journalism Review.